“Every kid grows up and wants to be a cowboy at some point in his life,” Mackey (Mac) Hedges says, “and some of us are cursed with never outgrowing it!”

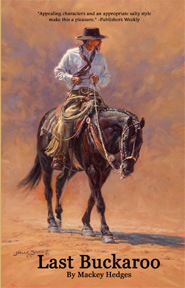

Mac is widely known for his acclaimed novel, Last Buckaroo, published in 1995 and the sequel to it, Shadow of the Wind, released in 2010. Last Buckaroo won the National Cowboy Symposium Working Cowboy Award and the Mormon Letter Fiction Award. Both novels recount a rollicking romp across the West as Tap McCoy, an aging buckaroo, gets paired up with an unlikely traveling partner, Dean McCuen, a young man recently out of military service looking to learn the cowboy trade. The earlier book is narrated by Tap and, in an unusual literary twist of focus, the latter is narrated by Dean. Some of the scenes from the first book are retold from Dean’s differing perspective in the second, with new adventures included to boot.

Mac is widely known for his acclaimed novel, Last Buckaroo, published in 1995 and the sequel to it, Shadow of the Wind, released in 2010. Last Buckaroo won the National Cowboy Symposium Working Cowboy Award and the Mormon Letter Fiction Award. Both novels recount a rollicking romp across the West as Tap McCoy, an aging buckaroo, gets paired up with an unlikely traveling partner, Dean McCuen, a young man recently out of military service looking to learn the cowboy trade. The earlier book is narrated by Tap and, in an unusual literary twist of focus, the latter is narrated by Dean. Some of the scenes from the first book are retold from Dean’s differing perspective in the second, with new adventures included to boot.

The duo grow to be inseparable friends while working and traveling together. They land jobs in cow camps, pack stations, ranches, and feedlots, and encounter all types of people and problems in the far reaches of the West. The tales that unfold at first may seem rather tall due to the craziness and absurdity of many situations that Tap and Dean find themselves in, but quickly the reader perceives a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction authenticity, and for good reason.

“Every person in that book, every place in that book, every story in that book, is true,” Mac says of Last Buckaroo (a fact referring to both books). “Now some of the people that were tall I made them short, and some of the people who were fat I made skinny, some of the Indians that were from Nevada I moved to Arizona, and I changed the names of all the ranches. To me, a writer is someone who has a good imagination and can come up with stories out of his head—I’m not a good writer. I can take a story that really happened and embellish it, but I don’t have the ability to just make things up. When I wrote Last Buckaroo I wrote down 16 stories for my kids. After I read it I thought, ‘They’re not going to read this.’ So I just kinda gave it a little fictional plot to make it interesting to the kids. So that’s how the story came about.”

Getting Mac off a horse long enough to write the first book took an unfortunate accident. In 1990, at age 48, the cowboy broke his back and pelvis when he got bucked off a horse while working for the Howard Ranch in northeastern Nevada. Being bedfast, his wife, Candi, talked him into using the down-time to record this remarkable window into a buckaroo’s world for their three boys. Even after the first manuscript was completed, it was a long trail before Last Buckaroo was published.

“I first sent it to Baxter Black—Doc’s the one who got it in print for me, really,” Mac explains. “He was the vet on the ranch next to me. He read it and said, ‘You know, Mac, what you’ve done? You’ve written about something nobody else has ever wrote about. … You’ve captured in print a history of the cowboy way of life that is fast fading. I don’t think there’s another contemporary western novel out there like this one. I’m going to send it back to you along with a letter of introduction to Gibbs Smith Publishing in Utah.’”

Gibbs Smith published the first edition in 1995 and the book was out of print two years later. It wasn’t until Robert Sigman, the former President and CEO of Republic Pictures, acquired a used copy of Last Buckaroo, read it, and felt so strongly that the book needed to be newly available that he pursued that goal and made arrangements with Mac for a new edition. Sigman went a step further and lined up the use of artwork by the late Joelle Smith to be part of the second edition—her familiar and iconic piece, Riata Man, became the front cover, and many of her prints grace the interior as well.

“Bob called me up,” Mac says, “and he said, ‘Hey Mac, the first one is really selling good—you ought to do another one.’ I said, ‘Well, if I ever get hurt again I will.’ And, within a week or two I got kicked and broke my leg. So I wrote the second one.”

Sigman published the follow-up book, Shadow of the Wind, again with a Joelle Smith piece, Ready to Rope, on the cover and other prints inside. The books are unquestionably unique. It’s not just the cowboying found in the plot—ranchwork, packing, breaking young horses, and such—that moves the story along, although there is plenty of it. The heart of the two buckaroos trying to sort things out in life draws the reader in.

Sigman published the follow-up book, Shadow of the Wind, again with a Joelle Smith piece, Ready to Rope, on the cover and other prints inside. The books are unquestionably unique. It’s not just the cowboying found in the plot—ranchwork, packing, breaking young horses, and such—that moves the story along, although there is plenty of it. The heart of the two buckaroos trying to sort things out in life draws the reader in.

There is Tap with his lifelong-loner buckaroo experiences, shrewd eye for what’s happening among a wide variety of western men, and more than a couple of demons that need exorcising but often get exercised instead. And then there is Dean, with his desire to do right, youthful ambitiousness, inexperience, and big secret he carries. The two men together grapple with life’s big decisions—when it’s time to leave an outfit, where to go next, who to call for work—and almost always when payday comes, alcohol turns their world upside down until they’re flat broke. All-in-all, the books paint an accurate depiction of the life Mac has experienced in his 70 plus years, even if the names and places have been changed and he’s colored a little outside of the lines. Still, Mac paints an authentic depiction of a buckaroo’s life in the latter half of the 20th century.

“I don’t want to take anything away from the guys that are out there now,” Mac says about the way things are shaping up for the cowboy today, “but the people who run around on four-wheelers, to me that’s not a cowboy. That’s somebody that works on a ranch. That’s a ranch hand, or something like that. But, the people that make their living ahorseback, now that’s a cowboy or that’s a buckaroo. I use the words interchangeably. I know that the guys out here who are [buckaroo] purists might get insulted if I call him a cowboy.

“I make my living working cattle. I worked in California down there on one outfit and all the guys on it tied hard and fast and they all rode grazer bits; a couple of them were some of the best cowboys I ever worked with. They could make decent horses and everything else. They didn’t make the fancy bridle horses like the guys up here [in Nevada] do, but they could make a decent horse that they could get the job done on. If I have my choice, when I start my colts I ride them in a snaffle until they’ve got a good handle, go to a hackamore, then I go to a two-rein, and then I’ll go to a real light spade. Something that doesn’t have a high port or anything like that because I get too heavy handed. Jerry Chapin told me one time—he used to run cattle on the YP—he told me there are a lot of men with spade bits but there’s only a few spade bit men. And, I’m one of these guys that owns a spade bit but I’m not really a spade bit man. … I’d like to be a good bridle horse man, and I can recognize one when I see one, but I never got to be good enough to ever do it. I can’t ever remember a time from the time I could walk, the only thing I ever wanted to do was be a cowboy or buckaroo.”

“I make my living working cattle. I worked in California down there on one outfit and all the guys on it tied hard and fast and they all rode grazer bits; a couple of them were some of the best cowboys I ever worked with. They could make decent horses and everything else. They didn’t make the fancy bridle horses like the guys up here [in Nevada] do, but they could make a decent horse that they could get the job done on. If I have my choice, when I start my colts I ride them in a snaffle until they’ve got a good handle, go to a hackamore, then I go to a two-rein, and then I’ll go to a real light spade. Something that doesn’t have a high port or anything like that because I get too heavy handed. Jerry Chapin told me one time—he used to run cattle on the YP—he told me there are a lot of men with spade bits but there’s only a few spade bit men. And, I’m one of these guys that owns a spade bit but I’m not really a spade bit man. … I’d like to be a good bridle horse man, and I can recognize one when I see one, but I never got to be good enough to ever do it. I can’t ever remember a time from the time I could walk, the only thing I ever wanted to do was be a cowboy or buckaroo.”

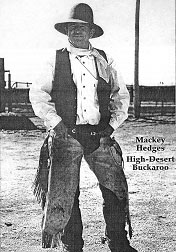

In his early 70s now, Mac has succeeded in his heart’s desire and is still buckarooing and spending a sizable chunk of his year packing into remote areas of Nevada, sometimes alone and sometimes working as a guide taking others along with him.

“I spent four years in the Marine Corps and every nickel I ever made except for four years in the Marine Corps in some way was related to a horse or a cow,” Mac says. “It’s one of them deals where I was born into it. I got my first horse when I was six. I’d been riding my dad’s horses and my grandfather’s horses all the time up to then.”

Mac was born in Illinois when his father was off fighting in World War II. His mother was staying with friends during her pregnancy. Just after Mac’s birth, his mother packed him up and moved to live with an aunt and uncle in New Mexico. His aunt was a Mescalero Apache. When his father returned from the war, the family moved to Washington State for a few years before moving the family back to New Mexico.

“Then from New Mexico we moved to Texas, and from Texas to Louisiana, from Louisiana to Kansas, from Kansas to Nebraska, and then I went into the Marine Corps,” Mac explains. “My father was one hell of a bronc rider but he was probably one of the poorest horsemen that ever lived as far as making a reined horse. He could ride horses that I couldn’t even get my saddle on, but he couldn’t make a bridle horse.

“You have to put everything in perspective of the time. There are more good horsemen today than probably any time in the past 60 years. There were a few good ones, but there wasn’t a lot of good ones. There was a period in there between prior to World War II and probably into the 60s that the good horsemen were around, but you didn’t hear anything about them. When I first started working on ranches in Nevada, you’d go to a ranch and there’d be one or two good cowboys, good buckaroos. And, there’d be two or three that were coming along, and then there’d be six or eight of us who were just like me—just guys who had all the tack and knew all the words, but we weren’t really good reined horsemen. We could sit there and steal a ride if they didn’t buck too bad. It seems to me that there was a period of time in there when they didn’t die out, but there got to be a hell of a lot fewer of them, and now today, you have guys that make their living—they’re not on ranches—they’re making their living as good horsemen. People have gotten to the point where they appreciate these top trainers, and these guys that are really good, they don’t stay out on the ranch.”

“You have to put everything in perspective of the time. There are more good horsemen today than probably any time in the past 60 years. There were a few good ones, but there wasn’t a lot of good ones. There was a period in there between prior to World War II and probably into the 60s that the good horsemen were around, but you didn’t hear anything about them. When I first started working on ranches in Nevada, you’d go to a ranch and there’d be one or two good cowboys, good buckaroos. And, there’d be two or three that were coming along, and then there’d be six or eight of us who were just like me—just guys who had all the tack and knew all the words, but we weren’t really good reined horsemen. We could sit there and steal a ride if they didn’t buck too bad. It seems to me that there was a period of time in there when they didn’t die out, but there got to be a hell of a lot fewer of them, and now today, you have guys that make their living—they’re not on ranches—they’re making their living as good horsemen. People have gotten to the point where they appreciate these top trainers, and these guys that are really good, they don’t stay out on the ranch.”

Mac moved between ranches and a pack station 31 times in about 20 years—not unlike the pace of wandering around Mac and Dean endure. The author experienced firsthand racial troubles that exist in America between blacks, whites, and Native Americans, and Shadow of the Wind in particular takes a hard, straight look at racial tensions through the experience of the characters.

“The biggest problem we have,” Mac says, referring to racial issues in America, “is that nobody will talk about it.”

Horses, of course, are a major vehicle helping to move the stories along. It’s not hard to get Mac on the subject.

“When I was at the YP [in Tuscarora, Nevada],” Mac says, “we had all big Thoroughbred horses crossed with Quarter Horses. At Ken Howard’s we had a Morgan stud, we used him on Quarter Horse mares—those Morgan horses were the toughest things up there in the mountains. They were fantastic mountain horses. Those Thoroughbreds could cover the desert like you couldn’t believe. When I was down in California on that Irvine [Ranch], we had a lot of real good, high-powered papered Quarter Horses. This is me talking now, I like them big old Thoroughbred-stud-on-a-Quarter-Horse-mare crosses, but right now I like short horses because they’re easier for me to get on. I couldn’t get on them big ol’ Thoroughbreds like I used to have.”

And, what about the title, Last Buckaroo? Why “last” buckaroo when it seems obvious, even in the books, that there are a lot of buckaroos out there still?

“When I wrote the book it was called The Slick Fork Saddle,” Mac explains. “Gibbs Smith called me in and they had a big conference and they said, ‘We don’t like your title. Nobody knows what a slick fork saddle is. They’re going to think it has something to do with eating utensils.’

“I said, ‘Everybody knows what a slick fork saddle is.’

“They said, ‘No they don’t.’ And they gave me a list of titles and they were all just far out, really wild, wacked out names. But the lady who was doing the editing was raised on a ranch up in Idaho and she came up with Last Buckaroo. I didn’t like it because that implied that that was about the last buckaroo, and thought well hell, there’s buckaroos all over here in northern Nevada and northern California. I had friends that said, ‘What do you mean, ‘Last Buckaroo?’ What do you think I am?’ It was the only one they had that I liked.”

Two-thirds of the first book got edited out by Gibbs Smith, Mac says. But with Sigman as his new publisher, Mac was given full license to write the second book anyway he liked—and he did.

“I was working with an old man one time,” Mac says. “We were sitting there talking and he said, ‘You realize, Mac, how insignificant we are?’

“I said, ‘Whatduya mean?’

“He said, ‘You think you’re on one of these outfits and you’re really important. You die, you move away…the ranch just keeps on running after you’re gone. You make no more impression on the people that you work with—you’re just a tool to make the ranch run.’

“When we were living on the reservation, my wife ran around with an old Indian lady, her name was Marie Bill. She’s dead now, and she lived to be 104 years old. She was alive when the Indians used to travel with the seasons. They made a big circle every year. She would tell my wife these old time Indian stories—what they call ‘winter stories.’ Marie Bill told her a Coyote story—it’s too long to tell you, but in the end my wife said, ‘She just laughed like heck after she told me this story—it doesn’t even make sense to a white person.’

“Anyway, the coyote, his family is starving and he shoots a rabbit and he tells the rabbit, ‘I’m sorry that I had to kill you to feed my family,’ and the rabbit says, ‘Don’t worry, Coyote, we’re all nothing more than the shadow of the wind. Once we leave, five minutes after we’re gone nobody even remembers we were here.’

“I was trying to get that across: five minutes after a buckaroo’s gone from a ranch, or a day later or a week later, nobody even knows he was there. I was working on one ranch over here, I’d been working on it eight years, and it sold. The new boss and I got kinda crossways and I quit and left. I thought, ‘This ranch is just going to totally collapse after I’m gone ‘cause nobody knows the country but me,’ and all this and that. That was the point I was trying to get across [in the second book]. You sit there and you think you’re pretty important. You know, it went right on after I was gone.”

Time marches on, and as timeless as these tales are, there is no denying the West is changing. If we hold these books up beside what we see happening today, many of those changes stand out. Luckily with Last Buckaroo and Shadow of the Wind we have a remarkable window into the buckaroo’s world of when Mac was a younger man. He wrote it for his children, and Mac says, “I wanted them to know what it was like in the days when we had big crews with eight, 10, or 12 buckaroos on a crew and you camped in tipi tents. Buckaroos are the guys who make 100 percent of their living working on the horse.”