What are some of the biggest obstacles that students of horsemanship face when working to achieve their horsemanship goals? Here we pose that question to three established teachers of horsemanship to discover what they see as being their students’ greatest challenges.

Alicia Landman is based in Nashville, Tennessee, She teaches lessons, from brushing up on basic horsemanship to refining the more advanced movements, and she offers training for horses. Alicia is available for clinics and lessons nationwide. For more, visit the Alicia Byberg-Landman Horsemanship Facebook page.

Alicia Landman is based in Nashville, Tennessee, She teaches lessons, from brushing up on basic horsemanship to refining the more advanced movements, and she offers training for horses. Alicia is available for clinics and lessons nationwide. For more, visit the Alicia Byberg-Landman Horsemanship Facebook page.

“I think them [the students] believing in themselves is probably the hardest obstacle,” Alicia Landman says. “I think a lot of times they’ll put themselves in the situation of having a new horse, or they’re getting a new relationship going between themselves and a horse. They try to compare themselves to everybody else and what they’re doing, without realizing maybe how much time the other people have put into what they are doing.”

A student who compares herself to others, Alicia explains, may not realize the work the other person has put into getting better with horses: the books that they have read, for instance, or the horses they have put their hands on to get to that level of partnership.

“And so, a lot of times with the people that I help, I just tell them, ‘You just have to kind of stay in your lane,’” Alicia says. “See what everybody else is doing and let that be an inspiration for you but don’t necessarily compare yourself, because some of them start to get down on themselves if they are not mastering something right away. I can’t speak for everyone else, but I know for myself, it took a long time of just watching and studying and then doing it a lot—and failing a lot—until things started to feel better. I try to encourage everybody just to not beat themselves up too much when they make mistakes because really, you have to make a lot of mistakes before it starts to feel good.”

For many years, Alicia trained horses for clients, but over time, she realized a downfall of that approach and turned her attention more towards teaching horsemanship.

“I really decided that teaching [horsemanship] was where I felt like I could help the most,” Alicia says, “because I was taking in horses for training and it was kind of depressing because you get the horses feeling pretty good about themselves and then if they go home, if the owners don’t understand what’s going on, then it just all falls apart. So it’s actually been a lot more fulfilling this way because the people that come, they want to learn. They’re consistent and they’re eager. And they understand that it is about them changing and not them changing the horse, necessarily. That makes it pretty fun.”

New folks often find Alicia by way of referrals. She says, many times those people feel like they are at a dead end in the progress with a horse.

“Trailer loading seems to be a huge thing that I’ll get phone calls for,” Alicia says. “And then they’re like, ‘Oh, you teach riding, too?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah I like riding—that’s why I’m in this, because I love to ride!’

“It’s funny how sometimes the really big problems that people are trying to fix, it’s like they don’t want to rip the Band-Aid off of that and work on those things, but eventually, they have to work on it. Then, I end up teaching them from the ground up because their groundwork is usually pretty poor…that’s why they can’t load them. So, it just goes from there.”

Alicia gets a wide range of clients—from Dressage riders, to some who like to rope, to others who just want to be safe riding on the trail.

“As far as the basics, I feel like I can do a pretty good job of getting them started,” she says. “I feel like most of them, across the board, they want to make more sense to their horses. They want to feel good about what they’re doing and don’t want it to have to be a struggle and a fight to do things. I feel like the people that I come across that kind of just want to skim the surface of riding horses generally don’t hang around for very long because the things that this type of horsemanship requires, some people are not willing to dig deep enough within themselves to make those improvements with their horses.

“Early on I used to get kind of upset because I just thought, ‘I’m not trying hard enough,’ or, ‘I’m not somehow speaking to them clearly about the things that they need to work on.’ But then I quickly realized that not everybody has the same goals in mind. And that maybe at that point in their lives they’re not ready to make those changes and it’s not up to me to force that change. They have to want to do the things that lead to better balance and a better mind with their horses. Realizing that helped me a lot, and there’s plenty of other people that do want to understand that and they want to study it. And they’re going to have to want to change to get to the really good stuff with their horses.

“The people that I see that really seem to go far and really enjoy it, and you start to see that their horses really enjoy them, and they’re having a good time, they’re usually the people that are not in a super-big rush to get everything done. They’re really just pleased by the process of trying new things every day. Those are the people that make it such a joy to help them, and I just come to work and go, ‘Wow, it’s not really even work!’ It’s just sharing the love of what you have with them, and they just grow every day. To me it’s just what keeps me going.”

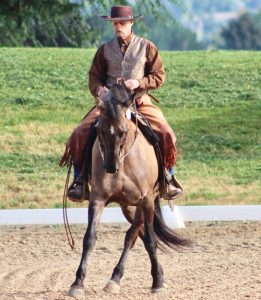

Jim Hicks teaches horsemanship clinics worldwide and co-owns Sage Creek Equestrian in Heber City, Utah, with his wife, Donette. He specializes in bringing dressage principles to horsemen of any discipline. For more on Jim visit: www.sagecreekequestrian.com.

Jim Hicks teaches horsemanship clinics worldwide and co-owns Sage Creek Equestrian in Heber City, Utah, with his wife, Donette. He specializes in bringing dressage principles to horsemen of any discipline. For more on Jim visit: www.sagecreekequestrian.com.

“The first thing that I encounter quite often is people who might have ridden horses when they were younger and then went into that part of life, into raising kids, and re-approach riding in their 40s or 50s,” Jim Hicks says. “In their head they’re still 18 years old, or whatever their memory was, so they had the physical ability and the mental confidence. And then what I find is when people mature and are a little bit older, they have more fear and their bodies don’t cooperate like they did when they were younger. That’s one scenario that you run into quite often.

“And then the other thing I find really interesting is that people tend to overestimate their abilities and underestimate what it takes to actually do the work. Depending on the personality, and their background sometimes, some people tend to get a little angry and fearful. Some people tend to be a little more emotional—maybe going to be a little bit of a victim—and they’re fearful so that they’re not able to offer the support that they [the horses] need at that particular time.”

Jim explains that fear and anger “live in the same room,” and that he works to help figure out what the right ingredients are to help based on the horses’ and riders’ personalities.

“And what it’s going to take to have them develop a relationship to where they’re communicating with one another in a way that is complementary to the rider and complementary to the horse,” Jim says. “If I was to narrow it down, probably to the biggest thing that I encounter when I go to a clinic or I’m here at home teaching or whether I’m starting somebody’s horse or whether I’m reschooling somebody’s horse or dealing with a competition horse, is unrealistic expectations as to what can be accomplished in a specific amount of time.

“Everybody kind of wants the miracle cure; they want instant gratification. There’s two ways to look at that. One is that it’s an expense. Those are the folks that are wanting to get the most in the least amount of time. Or there’s the folks who look at their horses as an investment. The investment could be for competition, an investment in their kids, an investment in living their dream—I find with those folks, they’re not afraid to allow for the time to develop things in a necessary manner. Humans by nature, I think, are impatient. And with a horse, just because they did something yesterday doesn’t mean they’re going to do it the same way today. That tends to frustrate a lot of people, because the thing I like to bring to their awareness is: we don’t function at the same level from one day to the next. One day we might be operating up there around nine or ten. Everything we are touching just turns into a little gold nugget; it just works. And then the next day it’s like shoveling mud. Every scoop we take out of there, seems like four more go back in. But if we can get to a baseline where we’re consistent from one day to the next, that’s where we become the most efficient and the most effective.

“So if you’re working, say your base line is like a five, what is it going to take to turn that base line into a six consistently? And if I can get people to start thinking in those terms, it seems like they start allowing things to happen versus feeling like they need to make them happen. And I think even as somebody that rides a lot of horses and is aware of that, it’s easy to lose sight of those things if we get tunnel vision; we see one thing and that’s all we can see. I really encourage people that no matter what’s going on between them and their horse, if I’m asking for one thing and the horse is offering something else, how do I make use of what the horse is offering on the way to getting what we’re asking for?

“It really is a process for people to start unpeeling their layers and to recognize what work they need to do with themselves. The next thing that is quite common in the beginning is people wanting to place the blame on the horse, ‘Something’s not working out; he’s not doing this or she’s not doing that.’ One of the things that I’ve incorporated for my students is: everybody, when they go to the shows, they have a blue ribbon day and they want to walk around and say I’m a winner, and on the bad days a lot of times they want to call their horse names or make excuses, placing the blame on the horse. And my point to my students and people is to become aware that whether it’s a blue ribbon day or whether it’s a day where you’re struggling, either way it is your responsibility.

“If you get to take credit for the blue ribbon days, you get to take credit for the days that don’t work out so good. First of all, they have to try on the idea and they want to have these breakthroughs. They have to incorporate that thinking of whatever is working with my horse or whatever is not working with my horse, it’s my responsibility. And what I see with people is, when they are able to get through some of this stuff, they don’t seem to be having the issues they were having before. And my point to them is: was the horse really having a problem or did you just learn how to communicate with him in a way that it was understood?

Another big thing Jim says he deals with is how people and horses process information.

“Most people tend to think, ‘Well I see the world this way, so my horse should see it this way,’ versus, ‘They have a different lens in which they see the world and preserve themselves,” Jim says. “What I tell people is: if your horse’s mouth is on your hand rubbing on you, that a lot of times humans want to make that be, ‘Oh, my horse loves me,’ versus understanding that to that horse, it’s not about loving them. It’s about how they move each other around. If they’re moving the other horse around, they are exercising their authority. So it’s really interesting to watch people have to figure out how to separate that out and establish the parameters of your space and my space in an interaction between the horse and the rider that honors what the other side needs.

“And another question I like to ask people is: what’s the difference between a pet and a companion? And that puzzles people a lot of times. But to put it simply, it’s just, a pet sits in your lap and a companion walks alongside of you. So I tell people: horses make wonderful companions and they make terrible pets because at the end of the day, they’re bigger than we are. If something spooks them and they don’t understand that, they’ll step on you and knock you down and then hurt you accidentally. But if they understand how to walk alongside you as a companion and there is a mutual respect of spacing between each other, then no matter what happens, the horse will find a way around you, not over you.

“To me it really doesn’t matter what you’re pursuing as far as do you want a stock horse, do you want to reiner, whether you want a cutter or a Dressage horse—I think the first thing is to have an appropriate fit between the horse and the rider. Everybody wants to be safe first and foremost. So the first goal is to help people be safe with their horses and then everything from there is easy.”

Mindy Bower starts colts and teaches horsemanship from her ranch, the Uh-Oh, in Kiowa, Colorado. Mindy is a dedicated student of horsemanship herself and is always looking to broaden her horizons of knowledge. For more information visit: www.uhohranch.com.

Mindy Bower starts colts and teaches horsemanship from her ranch, the Uh-Oh, in Kiowa, Colorado. Mindy is a dedicated student of horsemanship herself and is always looking to broaden her horizons of knowledge. For more information visit: www.uhohranch.com.

“The first thing I think of is that most of them [students] aren’t trying to arrange their life to take the time it takes to really study with somebody and really have the opportunity to indulge in immersing themselves,” Mindy Bower says. “Some think that a couple months is going to work, and it’s just not realistic. It’s kind of hard to get people to spend enough time.”

Sometimes even capable and dedicated students can spread themselves too thin, Mindy points out. She recently had a student who came to her mind as an example who, aside from staying at the ranch and working with Mindy, also was, “studying Spanish, plays piano, does American Sign Language, and her grandfather is living at her house and he needs constant care.” That might be an extreme example from a very driven student, but Mindy’s point holds up for many busy students from different walks of life.

Students sometimes come to live on the ranch and study with Mindy. Those pupils usually can “let that all go for a month” and concentrate on horsemanship, she says. But then back at home, all those other interests and responsibilities crowd back in and can side track from the time needed to get better with horses.

“It’s about getting time in the saddle,” Mindy says.

And there are other factors.

“What holds some people back…maybe it’s fear?” Mindy says. “Maybe people even know what to do but don’t have the ability to let go of the fear. The other part of it, there’s a lot of people who can’t take it. The horse is supposed to represent you; you’re supposed to look at yourself and improve through the horse because of the horse’s way of living.

“I think people get this thing that they’ve got to let go of the reins all the time and they can’t pick up on their horse. I don’t know where they get that. I don’t understand how you think you’re going to advance if you don’t try to put it together. You learn the ABCs, and then you learn words, and then you’ve got to learn sentences, not just saying the ABCs stage.”

Mindy also warns about students taking teaching the wrong way and putting pressure on themselves.

“You’ve got to be able to know that it’s not about a personal thing,” Mindy says. “It’s about listening to the information [a teacher provides] and being able to take it, and take responsibility for the information so that you’re not just staying in the same place all the time. The students’ perspective, it is like making a commitment. Take the time. You’re going to go to college for four years? Hey, make it so you can go study Horsemanship.”

[ux_custom_products cat=”magazine-subscriptions” products=”4″ columns=”4″ title=”Subscribe Today!”]