Story by A.J. Mangum

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.87

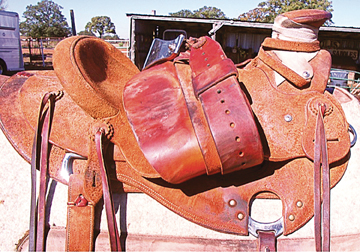

Oklahoma saddlemaker John Willemsma sheds light on a fundamental part of a saddle’s architecture.

In the horse world, the concept of saddle rigging can be confounding, to the point that many longtime riders throw around terms like “double rigging” or “centerfire,” or spout fractions – seven-eighths, three-quarters – without actually knowing their meaning or context. Here, saddlemaker John Willemsma, a Traditional Cowboy Arts Association member from Guthrie, Oklahoma, shares insight on this topic.

“There are two accepted formulas in determining a rigging position on one of today’s western saddles,” John explains. “The first – the formula I prefer – uses the low points of the saddle tree’s front and rear bar pads as reference points to determine the position of the rigging plate or dee. The second uses the low point of the front bar pad and the front point of the cantle, where it meets the tree, to determine rig placement.”

He shares the following rigging definitions:

Full position: the saddle rigging or dee is centered directly under the low point of the front bar pad.

Centerfire: rigging is positioned midway between the front and back low points on the bar pad.

Three-quarter: rigging is midway between the full and centerfire positions.

Seven-eighths: rigging is midway between the full and three-quarter positions.

Fifteen-sixteenths: rigging is midway between the full and seven-eighths positions.

Double-rigged: the saddle features both front rigging, in one of the above positions, and rear rigging, with a back dee attached to the tree behind the front point of the cantle on a saddle with full or seven-eighths rigging.

“Rarely is double rigging used on a three-quarter-rigged saddle, and never on a centerfire,” John says, adding that double-dee riggings are never placed further back than the seven-eighths position, as that would impede the stirrup leather’s forward swing.

“Seven-eighths flat-plate rigging seems to be the most popular on Wade-style saddles and saddles built on sweep-fork-style trees, such as Association or Will James trees,” John says. “It’s a strong rigging, made with two pieces of heavy leather sewn together. Because of its design, it provides an even pull over a larger area. The latigo will pull further back from the horse’s elbow, allowing for less interference as the horse moves.” With the addition of a back dee or slot, of course, a rider can add a back cinch for greater stability, useful for roping or traveling over rough or steep terrain.

“Three-quarter and centerfire rigging are rarely seen these days,” he adds, “but will find use in sagebrush country by horsemen who don’t like the extra weight of back cinches and billets. Those cowboys generally use long ropes, and run their dallies to slow down cattle.”

Rigging can be built with rings secured directly to a saddle tree (“on-tree rigging”) or built into the saddle skirt (“in-skirt rigging”).

“In-skirt rigging gained a bad reputation as many poorly made factory saddles used it with inferior results,” John says. “When done well, it’s as strong as any rigging style. A layer of quality leather is overlaid atop the skirt, attaching to the tree, and the rigging hardware is then riveted between those layers. In-skirt rigging offers the advantage of less weight, with fewer layers of leather than you’d find in a plate or double-dee rig. The disadvantage is that, if the rigging needs to be replaced, repair costs can be higher because the skirt will have to be replaced, too.”

John adds that he currently uses a saddle with in-skirt rigging – he likes the idea of less weight and bulk – but also makes regular use of a flat-plate-rigged saddle.

“Again,” he says, “it’s a matter of personal preference.”

Despite differences in the popularity of rigging styles, John points out that, if a saddle is properly built, any rigging option can work well. Selection of a rigging style, therefore, becomes a matter of utility and personal choice.

“Whatever rigging option a rider chooses, it’s of the utmost importance that the rigging be in the same position on each side of the saddle,” John says. If rigging positions are mismatched, he explains, the saddle will not pull evenly on the horse’s back, causing the saddle to ride crooked and creating a long list of other problems. It’s also vital the rigging leather be cut from the best parts of a hide to ensure strength.

John adds that a saddle’s rigging position will not determine the saddle’s position on a horse’s back. Poor saddle fit is most likely attributable to tree design or to the rider overpadding.

A.J. Mangum is the editor of Ranch & Reata. Learn more about John Willemsma’s work at www.tcowboyarts.org.