Story by A.J. Mangum

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.85 Subscribe Today!

According to bit and spur maker Wilson Capron, the secret to effective design lies in a ratio that’s all around us.

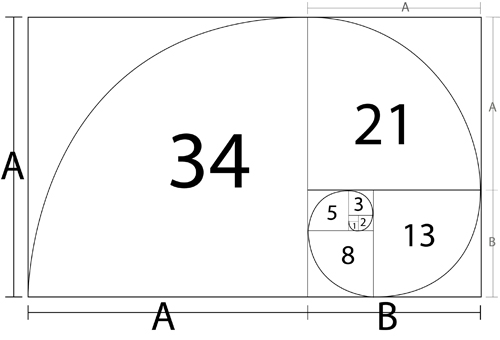

In mathematics, there’s a formula known as the “golden ratio” that’s frequently encountered in measuring distances within basic geometric shapes. Expressed simply, or as simply as an important math concept can be expressed, this numerical relationship exists when (bear with me here) the ratio of two numbers (a and a smaller number, b) is the same as the ratio of their sum (a+b) to the larger of the two numbers (a).

When a and b (say, the length and width of a rectangle) have this specific relationship, their ratio works out to 1:1.62. Just to get the rest of our math out of the way, here’s an example: the ratio of 34 to 21 equals 1.62 (the result of dividing 34 by 21, followed by some minor rounding), just as the ratio of their sum, 55, to the larger of the two numbers, 34, equals 1.62. (Relax. The math is over.)

The frequency with which the golden ratio – also called the golden mean, the golden section, or the divine proportion – pops up all around us has given it something approaching a mystical quality (hence that “divine proportion” business), making it an object of fascination for mathematicians. Once you know it exists, the ratio is hard to escape. It can be found throughout nature – in the arrangements of flower petals and leaves, and in pine-cone patterns; in the spiral shapes of sea shells and galaxies; and even in the dimensions of a DNA molecule. Some mathematicians have described the golden ratio as a universal law guiding the makeup of anything “striving for beauty and completeness.”

For centuries, perhaps in an effort to mimic natural beauty, artists of all types – painters, architects, book designers, fashion designers, industrial designers – have relied on the ratio of 1:1.62 to establish the dimensions for their work. The approach has consistently delivered aesthetic appeal in every creative medium, though even its advocates would be hard-pressed to explain the mechanics at work: we don’t know why we like the results; we just do. The magic of the golden ratio is that it creates work with dimensions that are naturally appealing to the human eye.

Texas bit and spur maker Wilson Capron, a member of the Traditional Cowboy Arts Association, makes extensive use of the golden ratio in his work, using the formula to establish initial boundaries for his designs. He credits his father, artist Mike Capron, with introducing him to the concept.

What prompted that introduction to the golden ratio?

I was having a hard time with some designs, and went to my dad with questions. He showed me that if I designed within boundaries – areas with dimensions set by this ratio – I’d get more pleasing results.

What are the mechanics at work? It isn’t a matter of using rectangles as design elements.

I’ll create rectangles [with dimensions bearing the 1:1.62 ratio] on paper and design within them. That’s the canvas. That approach can help determine how wide a bit shank should be, or how the space within a heel band should be used, or the arc on which a scroll should be drawn. The ratio gives me boundaries. It doesn’t mean I can’t go outside those boundaries, but it’s a starting point, a pleasing shape to begin with.

What do you like about the golden ratio as a design tool?

As a designer, when you look at a blank piece of paper, it’s hard to make that first mark. But when you know there are examples in nature, in art, in architecture, that are successful, that are proven, that hesitancy is replaced with excitement and curiosity. This ratio lets me start with parameters that I know will work. It also helps me be consistent. I have a mathematical basis for what I’m doing.

How apparent is the golden ratio in your work? Can a layman see it?

It would be hard without knowing the math and seeing those original rectangles and sketches. The idea is that the resulting shapes and arrangements look good. A viewer might not even know why it looks good.

Going all the way back to the Egyptian pyramids, Roman architecture, Da Vinci and Michelangelo, it seems to be a centuries-old mystery, maybe an unsolvable one, as to why this ratio produces shapes pleasing to the human eye. Do you have a theory as to why it works?

Because “they” said so (laughs). The ratio breaks up shapes really well, and creates sections that allow a variety of compositions. I’ve run this past craftsmen I look up to, great designers who don’t use this ratio, who’ve maybe never heard of it. I’ll put a “golden rectangle” over one of their designs and they’re always close. Those craftsmen are using the ratio without knowing it. They just know when a rectangle looks good. When a designer hits on something that’s working well, that designer is probably falling into these parameters, albeit unknowingly.

Is this something you teach in your workshops?

Yes, but I’m careful about it. Students have to be into it to grasp it and to want to pursue it. If you go into it too deeply, too quickly, you get a deer-in-the-headlights look. You lose people quick. But I do encourage students to use it. There’s a book I recommend, Geometry of Design, by Kimberly Elam.

Some artists and craftsmen must be resistant to the idea.

It’s certainly contradictory to modern art, in which artists are told to get outside of these confines. But then, modern art is often hard to understand. And, as the saying goes, just because no one understands you doesn’t make you an artist.

A.J. Mangum is the editor of Ranch & Reata magazine. Learn more about Wilson Capron’s work at www.tcowboyarts.org.