Have you ever had anyone poke you in the ribs? Did you tell them to “quit it!” because it was painful or ticklish? Maybe you have learned how to stiffen your ribcage so that when your friend poked you it didn’t hurt. This is what I learned to do as a kid living with a brother who took every opportunity to tease me. But it means you have to restrict your breathing and movement between the ribs.

Most people don’t like being poked in the ribs and most horses don’t like it either. When you are sitting on a horse you have a lot of contact with his ribcage. Did you realize your saddle rests on the muscles over his ribs and that the ribcage is actually what is supporting you? Also your legs go around the ribcage and lay directly (depending on how fat your horse is) on against his ribs which we tend to think of as his sides without recognizing the individual ribs themselves. Many horses don’t mind the pressure you’re your legs or spurs if you use them kindly. However there are horses that will pin their ears, stiffen and buck every time you use your spurs. They are trying to tell you to quit poking them in the ribs!

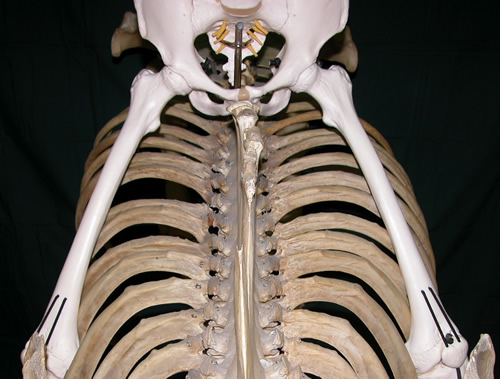

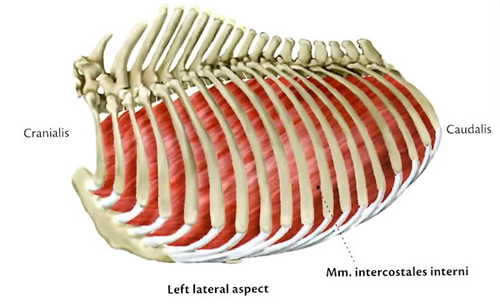

The basic design of the ribcage is similar for both horses and humans. It is comprised of the sternum or breastbone, the thoracic vertebrae (the part of the spine which is associated with the ribs) and the ribs themselves. Ribs are paired elastic arches of bone, two for each thoracic vertebrae. Some ribs articulate (join) directly to the sternum and are called true ribs. The remainder are called false ribs because their cartilage attaches to the cartilage of the ribs above instead of directly attaching to the sternum. Finally, there are floating ribs – these do not connect to the sternum at all. You have two sets of floating ribs but horses typically don’t have any. The function of the ribcage is to protect the internal organs (heart and lungs) and assist in breathing.

The sternum is a combination of cartilage and bone and never gets completely bony. It has two segments that are mostly cartilage. The cranial segment (closest to the head or cranium) is called the manubrium. It is shaped like Superman’s shield. The caudal segment (closest to the tail) is called the xiphoid process (this makes a great Scrabble® word for the letter x!).

You can feel your sternum by placing two fingers at the base of your throat where your collarbones come together. Right in the middle is a small “V” shape known as the sternoclavicular notch (sterno = sternum, clavicular = clavical or collarbone, notch =“V” shaped cut in the edge of the surface). The bottom of the “V” is the top of your sternum.

Trace your sternum until you get to the end. Press gently! You might feel a little process sticking down just below where the lower ribs attach. This is the xiphoid cartilage. From the bottom of your sternum carefully trace the edge of your ribs as they sweep down and back. Follow the edge of your false ribs until you come to your floating ribs.

You will know you have found the floating ribs because you can feel the ends of each; they are not attached to the other ribs. Continue tracing the floating ribs back towards the spine. The ribs will begin to curve up again as you get closer to the vertebrae. You may not be able to feel all the way because of the back muscles that overlay your ribs. Notice the depth of your ribcage by placing one hand on the front and one hand on the back at the same time and then on each side. Finally feel along each side of your sternum starting at the top and see how many pairs of ribs you can identify.

Next time you are at the barn spend a minute or two exploring your horse’s ribcage. If he is very fat this may be a bit of problem so you might want to find a thin horse to explore until you know what you are looking for. Go gently and carefully– some horses are uncomfortable in different parts of their ribcage while others might think you poking like a large horsefly!

Place your hand between the horse’s front legs on the chest. You will feel a hard bump sticking forward like the prow of a ship. This is the cranial portion of the horse’s sternum. Follow the sternum between the horse’s front legs with one hand tracing its shape. Then stand to the side, place your hand between the horse’s front legs from behind the elbow and trace the sternum forward as far as you can go – be careful! Some horses are very sensitive in their girth area!

Follow the sternum from the chest back to the back end. You may feel the xiphoid process on some horses and not on others. Locate the horse’s girth groove behind the elbow. This is actually a groove in the horse’s sternum. Next time you tighten your girth remember you are putting pressure here.

Next find the horse’s ribs. It is difficult to feel ribs if they are overweight because they are covered with fat. However if you start at the back, in the flank area, you might feel a hard edge. Trace this up towards the spine. Notice how it sweeps forward as the ribs get closer to the vertebrae just like yours. Finally run your fingers down the sides of your horse. Notice the overall shape of the ribcage and how it is narrow towards the sternum. Feel for the hard surface of the ribs along the horse’s sides with a line of soft tissue between each one. If you follow the ribs towards the spine you might even feel a slight shelf. This is where the rib changes angle as it curves toward the vertebrae.

Now that you have explored both you and your horse’s ribcage I hope you realize how similar we are. The biggest difference is the number of ribs and the overall shape of the ribcage as we just explored. In terms of numbers humans have 12 pairs of ribs; 7 pairs of true ribs, 3 pairs false ribs and 2 sets of floating ribs. Horses have 18 (occasionally 19) pairs of ribs; 8 pairs of true ribs and 10 pairs of false ribs. Occasionally horses have floating ribs and sometimes these are unpaired (only exist on one side).