“I just want to go on a trail ride with my horse.”

The anthem of so many riders. Myself included. There are plenty of horses who will happily pack people down the trail. I don’t happen to own such a horse and the price to buy one in New England is quite high. So my quarter horse, Moxie, has given me the opportunity to analyze what a horse might need to line out happily on the trails.

I am fortunate to have found Piper Ridge Farm and the horsewoman-in-residence, Libby Lyman. Libby explains that trail riding can trouble a horse because many “people keep their horses confined in a relatively small world. Then they pressure them to leave their home base and herd and head into what the horse perceives as dangerous territory. Many people will push the horse to go away from where they want to be. This adds pressure to the scary thing, making it worse. Now the person, who is causing the pressure, is considered part of the problem instead of a trusted leader. People can get by with a horse if the “trail ride” becomes a routine, but when they leave the routine or something interrupts the routine, the horse can fall apart.”

For a select group of her clients, Libby offers Trail Clinics. These are four-day clinics. Libby works with two groups of horses and riders each day, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. She groups together those who have similar issues and strengths. In her 2016 trail clinic the bolder more experienced horses and riders worked in the morning while the greener, less confident group went in the afternoon. Everyone in this clinic had some basic skills and understanding of the principles of good horsemanship.

The groups were small (4-5 horses) to facilitate communication. Libby has headsets and microphones for every rider. Her system allowed all of us to hear and to talk to her. Libby could coach any one of us moment-to-moment.

There is a carefully considered progression to Libby’s format for these trail clinics.

We began in the arena. Libby believes it is really important to understand each horse and rider and to address their weaknesses in a controlled environment before you approach the big bad woods. In Maine, we have woods. Lots of them. Best to have some skills in place before meeting a moose.

Eclectic Horseman readers know of the basics we worked on: getting the horse with you, helping them yield to pressure, getting the hind end to yield and recognizing straightness whenever it comes. These, and more, are essential for trail work.

First off, the riders and Libby checked where the horses were by themselves in the arena. She determined how strong the inter-species connection is. Could the horse get with their rider, mentally and physically? Could they get with their rider when horses and other distractions were calling for their attention? Then she had the group explore inter-equine issues. Was one horse defensive around other horses? Did they latch on to another horse and have trouble separating?

An important aspect Libby worked on in the arena is how a horse and rider deal with fear. How fearful were they in general? How did they express themselves when afraid? What specific actions were they afraid of?

Sue Taylor rode her fjord, Bacchus in the morning group. They do a lot of trail riding. “I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t even have a thought about what my horse or the group of horses might present, never mind about how we’d work on it. It was all brand new to me which is odd because I’ve been riding for years and years. In the thousands of lessons I took, trail riding was never taught… I was surprised at the time we took to get the horses ok with each other…It was clearly valuable time spent. And as fundamental a concept as it was, I had never thought to spend the time getting horses ok with each other at the trail head of any ride before.”

Bacchus was concerned about horses coming up behind him. Libby had Sue ride with a tarp letting Bacchus move out and away from it. At one point Bacchus became too scared so Sue let the tarp go. She turned Bacchus back toward it so he released into it. They began again with the tarp crumpled up. Bacchus felt better about that, moving out freely forward.

After the arena work, Libby helped Bacchus and Sue deal with the coming-from-behind fear out on the trail. Sue observes, “Bacchus was significantly worried about being the last horse in the line of trail horses. He would push his way to the lead position where I could feel that he was more comfortable. Prior to the clinic, I would let him push to the lead position and let him stay there when riding with others that didn’t mind. I avoided riding with others if we had to ride behind because he carried a lot of worry and the tug-of-war between us to keep him behind made the ride no fun. So my strategy prior to the clinic was avoidance.”

“Libby had me allow Bacchus to push to the front, then once in the lead position, we’d peel back to the end of the pack. Again and again, he’d be allowed to push to the front. Again and again we’d peel back to the end. Maybe the third or forth time, he settled in the second spot and we let that work out. There was no pulling to keep him there; he had settled himself there and rode along nicely.

“The next ride in the clinic, he settled mid pack and then later, settled in the rear position. He rode comfortably there like never before. No pushing, no tugging on the reins and so much less worry. This was a significant change. I went home, rode with others and it held. It is so great to know Bacchus can be ok in any position within the trail pack now that I have some understanding of his thinking and a strategy to change his thoughts.”

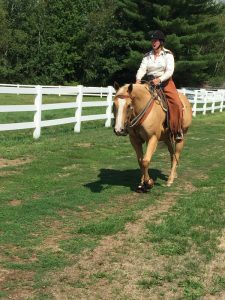

The afternoon group consisted of horses and riders who wanted to go a bit slower. Libby rode her young, green Lusitano mare in this group. Moxie and I were in this group. As Bryan Neubert observed, Moxie is afraid of being afraid. I joined this clinic to help me and my horse gain more confidence. Another member of this group was Laurie Bryan and her curly horse, Pyewacket. She joined this clinic because she wanted “To ride with a great group of people and have opportunities to learn how to support my horse and other horses better on the trail.”

As Libby remarked, mixing in the young Lusitano was an opportunity “to help the people see the difference between patterned fear and a young horse’s curiosity. The green horse is less likely to have gotten into trouble. The older horses have often been driven into trouble.”

During the arena work, Libby helped Pyewacket deal with her concern about “being able to move other horses in the group away.” Laurie remembers, “Before we went out on the trail, Libby set it up so we were in a group of horses and as Pye and I approached a horse, the rider encouraged their horse to move off so Pye felt she was in control – moving the horse away. It was a small thing and took almost no time but made a huge difference to Pye. Moving them off, allowed her to relax and be out on the trail in the front, middle or rear of the group without getting tense. I’ve used this strategy at home when riding out with new horses and it allows Pye to gain confidence and settle for the ride.”

For the green and fearful horses in this group, Libby set up a “mini-crisis.” She had Nancy Huntzberger and her mare Goody move with a tarp unfurled fully behind. The rest of us could approach the tarp as it moved away. Libby says, “An object moving away from them is the least scary. It creates the possibility for a person to encourage the horse to look at it and have their curiosity come up. That starts to build confidence in the horse that when the person asks them to do something it could be successful.”

Dealing with the mini-crisis of the tarp helped us when we rode outside. We came across a vicious lawn mower setting in wait in the middle of a field. Unlike the arena tarp that moved away from us, this terrifying thing just sat there ominously waiting. Using the principles we used for the tarp and building off each other’s confidence the horses eventually conquered this squat monster and moved past it with ease.

Laurie learned “to support Pye so she could approach a scary situation, keep a straight line and carry us through/past it on a loose rein. The feel of Pye carrying us without any tension was fabulous.” She was surprised at “how relaxed Pye became riding out with a group of horses. When we picked up speed she didn’t get wound up and she was able to leave the group and meet back up with them without worry.”

One group may need a lot of time near fences but by the fourth day both groups spent a lot of time out in wood and field. Libby would look for places where our horses were concerned and we would work in those spots for as long as necessary. Every scary house or threatening lawn mower was an opportunity to get clear through to the horse. Once out on the trail, we would stop and go as needed.

For instance, Moxie can get quite concerned about horses leaving him on the trail. Every time we would start up after halting, Libby would have Moxie step off first, even if he was in the middle of the pack. This way he never felt left behind. Gradually, he and I felt more and more confident that we would not be left behind. Libby’s clients were all extremely supportive of one another’s needs.

Sue Taylor observed that the work is the work, whether in an arena or among the pines. “There is a “pushing through me” in my horse that shows up big on the trail, and it is the same “pushing through me” in the arena. The trail has helped me to know how necessary it is to recognize and address it even in its smaller forms when riding in the arena.

“The same goes with straightness and carrying himself from behind. This is not just an arena thing. When I can engage his mind and can feel the power coming from his hindquarters and the lift in his back, it’s a wonderful ride no matter where we are riding, the trail or the arena or anywhere else.”

Straightness is something I am just learning to recognize and search for. Riding out on a trail with other horses is more interesting than making circles in an arena. This trail clinic offered many moments when I felt my horse take an interest and line out straight. Libby coached me to fully release in these moments. Moxie really appreciated that.

Dealing with the trail obstacles and real life situations helped Laurie, “Experience the feel and importance of straightness…whether I’m leading her, asking her to stand for the vet or farrier, loading on the trailer or any other task – when she’s straight and has let go of other thoughts, she can lead through a scary place without rushing or stand without fidgeting. Watching/feeling for the straightness lets me know in advance how she’s feeling and where she’s thinking which helps me support her in many situations.”

These trail clinics are not for people who want to gallop romantically and carefree through the pine forests. Well, they are…but Libby teaches us that before we gallop towards the dream we best check if we can step one foot at a time, with understanding and skill. Best check that we know what to do when a lawn mower attacks. Best check on how supportive your friends riding with you can be. Best ask your horse to feel good about being with you. Libby teaches us that the work is holistic, it happens in every moment you interact with the horse. The carefree gallop awaits, after the careful consideration of true support. Libby Lyman, for me and Moxie, is a true support.