Written by Sue Stuska, Ed.D.

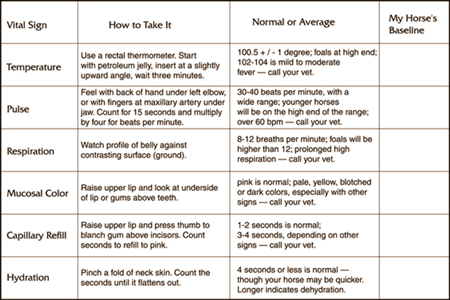

These six vital signs give you clues to evaluate your horse’s well-being. Vital signs readings give you information that can help you figure out whether he’s OK or sick.

If he’s sick, they can help you determine how sick. They help you determine whether or not to call the veterinarian. (Anytime you’re in doubt, call the vet.) When you do call the vet, telling him/her the horse’s vital signs can help the vet determine how serious the problem is and what type of problem you are facing. Your vet will thank you for being an informed horse owner when you can provide this vital information over the phone. The vet will also need to hear your observations of how the horse is acting and what events preceded the situation.

Determine what is normal for your horse. This way, when you think there might be something wrong, you can compare readings.

Learn to take the readings efficiently before an accident or emergency. When the time comes, you’ll be able to concentrate on handling an upset horse—not on the technique of getting the reading. You may need help to find the pulse site, for example. In all cases, feel free to repeat the reading to get an informal average.

Too, you may notice holes in your horse’s training during your initial readings that you can work on for the next time. You don’t want to put yourself in danger, or have to dance around in circles, with a horse who won’t stand quietly, with his head down, and pay attention to you.

Once you’ve mastered the techniques in this article, challenge yourself and your horse to get these readings in distracting situations. This way, you further his training, make him safer for you to work around, and allow you (or the vet) to work with him even if he is sick or badly hurt in a tumultuous setting.It’s also helpful to know what might cause abnormal readings so you can interpret the results; we’ll give you some possibilities.

Temperature

If you own a horse, you should own a thermometer and know your horse’s baseline temperature. See “Taking Your Horse’s Temperature” in Eclectic Horseman, Issue No. 4, Mar/Apr 2002.

Normal situations that will cause an increased temperature are exercise; excitement; high air temperature particularly if it’s also humid; and merely standing in the sun. These should not cause a prolonged reading in the fever range, though.

Problem situations that can cause an increased temperature—into the fever range—are sunstroke / heatstroke and infection. Whether the infection is localized or widespread, the body temperature increases in an attempt to create a hostile environment for the bacteria or virus.While beneficial at the start (it creates a hostile environment for the invading organism), too high a temperature for too long causes dehydration and tissue damage (particularly nerve/brain tissue). The horse needs veterinary attention to fight off the infection and reduce the fever.

Problem situations that can cause a temperature decrease are shock (from a serious wound, for example), hypothermia (the body is unable to keep itself warm), starvation, and poisoning. A mare may show an abnormally low body temperature during foaling; this is not a problem.

Pulse

The pulse is the measure of the horse’s heart rate, reported in beats per minute (bpm). For diagnostic purposes, it is taken at rest. The average resting pulse rate varies widely; 30-40 bpm is common. Young horses will be on the higher end of the range. Time the pulse for 15 seconds and multiply by 4 to get the reading.

Fifteen seconds of counting is the informal standard for pulse and respiration detection time. It gives you a slightly more accurate number than counting for 10 seconds and multiplying by 6. It is more reliable than counting for a full minute where a slight movement by the horse can disrupt your count.

Press the back of your hand (to avoid confusing your own pulse from your fingertips) deep and firmly behind the horse’s left elbow. This place is the closest to your horse’s heart, and you can actually feel the heart beat if all else is quiet. Regardless, this area may be your first choice if the horse is fussy about his head from illness or injury.

Or, feel the pulse at the common location: the external maxillary (jaw) artery. This pencil-sized artery runs around the lower edge of the lower jaw and is easiest to feel by pressing your fingers (not your thumb, which has a stronger pulse than the fingers and can be confusing) over the artery. It takes a little practice to find the artery, partly because it will roll around and out from under your fingers and partly because if you press too hard, you’ll restrict the flow. If you can’t find the artery on the left side, try the right jaw; the artery may be bigger on one side than the other. Don’t hesitate to ask your vet or an informed riding friend to show you how to find it if you have trouble.

Natural things that can cause an increased heart rate include work (the rate can go well above 100 bpm during strenuous work; the quicker the rate returns to normal, the better the physical condition of the horse). Nervousness, blood loss, and hot weather/being overheated/heat stroke will also, predictably, cause an increased pulse.

Abnormal conditions that cause an increased pulse are many, including pain, infection, shock, blood loss, heat stroke and dehydration. Other vital signs, diagnostics, and a look at the situation are needed to narrow down the cause of the increased heart rate. An abnormally slow pulse is rare, but may be seen in cases of severe exhaustion or excessive cold.

Respiration

If the horse is still and quiet, and you can see his nostrils move, you can count respirations that way. It’s possible that you can hear him breathe—but probably only if there is an increase for some reason, or a breathing difficulty. Don’t rely on feeling his breath on your hand because he may sniff at your hand (which will increase your count artificially). The most consistently available method is to watch his ribs fill and deflate. To do this, stand where you can see the profile of his ribs. It’s easiest to do this by standing at his side and looking across the profile of his belly toward a contrasting surface (the ground works well). The left or right side works equally well.

Count breaths for 15 seconds and multiply by 4 for the breaths per minute. Anywhere from 8 to 12 per minute is normal for an adult horse. Don’t be surprised, then, to count only 2 breaths in 15 seconds.For easiest counting, hold your watch up where you can see it and the horse’s belly profile at the same time. Find the tempo of the breaths before you start counting. You can count either inspirations or expirations, whichever you find easiest (but don’t count both!). Often, particularly when resting, the horse will breathe in, pause, and breathe in the rest of the way (or exhale this way) so count “1” either way. Foals’ respirations are naturally higher, as are hot, excited, or working horses and pregnant mares. Abnormal increases are caused by pain and fever.

Mucosal Color

The color of the mucous membranes of the horse can show the situation with his blood. This is much the same as with humans, though we gauge by our lips or nail beds. For the horse, you can use the lining of the eyelids or the inside of the nose (on a horse with pink skin here).

However, the easiest place to detect color differences—because of the size of the area—is inside the mouth. You can use the underside of the lip and/or the gums above the incisor teeth. Work with your horse until he will allow you to curl his upper lip back and expose the pink mucosa, then stay still while you take a look.

Pink color is normal. Pale pink can show anemia, shock, or severe blood loss. Red may mean fever, severe dehydration, or toxic shock. Red blotches (hemorrhages), small or large, point to disease. Blue-grey, purple, or very dark red can show lack of oxygen from some heart problems and a few poisonings. Yellow color is called jaundice; it comes from excess bile in the blood and may be due to icterus (various diseases pertaining to jaundice) or liver problems. A horse temporarily off his feed may look yellow for a short time, though this is not a serious problem in itself.

Capillary Refill Time

After raising the horse’s upper lip, press your thumb firmly on his gums above the incisor teeth to press the blood out of the tissues. After a second or so, remove your thumb and you should see a blanched thumbprint. This area should refill with blood (return to the pink color of the surrounding tissue) within 1 to 2 seconds. You can get an accurate enough count by the “one thousand one, one thousand two” method. If the capillary refill takes 3 to 4 seconds, this means the horse has re-routed blood internally. In the presence of other diagnostics, this can indicate an internal problem, disease, shock, or circulatory failure.

Preparation

Valuable information can be gained by a few minutes of fact-finding. Take a few minutes next time you work with your horse to learn his normal readings. Taking the current readings whenever you need to call the vet about a problem will help give vital clues to your horse’s condition. The diagram at right can be photocopied or clipped out and used as a worksheet to be prepared and know your horse’s baseline readings.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.8