Written by Wendy Murdoch

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.64

“Jambo!” the soft musical voice of the Daniel floats through the tent flaps as hot coffee, tea and cookies arrive to wake us with the dawn. Dressed and ready to ride we make our way down to the mess tent where we have a light meal of toast and jam then head to the picket line to find our horses. They are already tacked and waiting for us, having had their morning nosebag and hay net in the darkness. We put on our saddlebags, lead our horses away from the line and mount up for another ride in this breathtaking land.

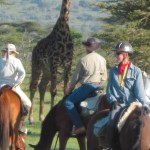

As we ride out from camp we are greeted by the gentle sounds and sights of giraffe, tope, Thomson’s gazelle, Grant’s gazelle, impala, silver-backed jackal and a soft morning light as the sun leaps into the sky. The Masai Mara, named for the people who live here and the spotted appearance of the land created by trees, shrubs, savannah and cloud shadows, lies just below the equator at an altitude of 5000 – 7000 ft. This broad relatively flat land is within the Rift Valley Province in the southwest corner of Kenya, southeast of Lake Victoria.

The Masai Mara is the northern continuation of Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park and lies within the Great Rift Valley which is a fault line 3500 miles long from Ethiopia’s Red Sea through Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi and into Mozambique. The Rift is a fissure in the earth’s crust, which continues to widen very slowly. As we drove to the Mara from Nairobi we crossed over the mountainous edge of the Rift Valley providing us with a sweeping view of the valley below featuring Mount Longonot, an extinct volcano.

For several months each year the Mara is home to the largest land animal migration in the world. From July through October the wildebeest and accompanying grazers including zebra, Grant’s gazelle, Thomson’s gazelle, eland and impala cross the Mara River following the rains and short sweet grass. For millennia more than 1.5 million animals make the endless pilgrimage in constant search for food and water.

Calving begins January – March in the Serengeti with an estimated 400,000 calves born within a six-week period. By May the food supply runs out, starting the journey northward through the Serengeti’s Western Corridor. Depending on the rain they reach the Mara River beginning in July. Wildebeest crossing the River is one of the greatest spectacles in the world. Depending on the water’s depth it can appear to boil with drowning wildebeest and slashing crocodiles. Once safely on the other side they fan out across the plains. As we ride along, the wildebeest appear as tiny black dots stretching on for miles. Suddenly one will start to gallop and the entire herd will follow until the leader stops again to graze for no apparent reason. As the food source runs out and the rains move on they once again across the Mara River in search of greener pastures in Tanzania.

Moving day and it is time for the entire camp to be broken down and transported to our next campsite. The entire operation moves every two days during this 9-day trek for a total of 4 camps. With no towns for miles everything is packed out in trucks to the first camp in advance of our arrival including food for 15 guests, the crew (numbering more than the guests) and horses. We pack our bags and place them on the canvas laid out near the mess tent and sit down to breakfast – oatmeal with golden syrup, bacon, eggs, toast, granola, yogurt, fruit and juice. We will be riding for several hours before we stop for lunch where the vehicle will meet us. Mid-safari is the long day (approximately 35 km). We pack a sandwich and snacks because we won’t be seeing the vehicle that afternoon. The temperature is comfortably cool in the morning as we head out at dawn and warms to mid 80’s during the day but being at altitude it is dry and pleasant with a surprising lack of bugs! There are more mosquitoes in my back yard than in the Mara.

We leave camp and head out across the open plains. The scope and magnitude of the Mara takes some getting used to. The land is open and broad, and you can see the curvature of the earth on the horizon over the dried grasses waving in the gentle breeze dotted by thousands of wildebeest. One gets the sense of what it must have been like in the Great Plains in America 400 years ago when huge herds of buffalo roamed the plains. For the entire 9-day safari we never see a fence, go through a gate, or cross a bridge on horseback.

At one point, James, one of our Silver Badge guides, spotted a herd of 60 elephants 5 miles away across the border into Tanzania. We weren’t accustomed to looking out at such distances. Nor did we see the chameleon in the grass as we rode past. Gordie, owner of the outfitting company Safaris Unlimited, dismounted and held out his arm for the little fellow. He crawled up and changed to the color of his khaki shirt while his stalk-like eyes moved in opposite directions. When he crawled onto a nearby tree he changed to gray and brown and became as invisible as he had been in the grass.

There are so many layers with which to filter the experience of riding horseback through the Mara. The skies are wide and grand with rich reds, oranges, blue, purple and pinks. During the day the clouds billow up for miles creating giant shadows across the land. We take it all in: The openness of the plains that suddenly drop down along a river or escarpment. The sway where the antelope are quietly grazing but move off as we approach. We gallop along with the herds following the undulating surface under the horse’s hooves as the gazelles and impala follow the contours of the slope.

With the rains come flowering plants and trees that burst into life with soft puffy tufts of yellow and pale white or deep pinks, yellow, purple or brilliant white flowers. Some so small you might overlook them while others stand up proud and willing to show off their shape and color.

The trees are so different and varied. Thorny acacias, which the elephants consume like candy. Yellow fever trees with striking yellow and green bark that glows when the morning sun shines upon them. Flat-topped thorn trees with nature’s pruning as only a giraffe could do. Comfortable tree trunks and shade to settle under with a saddle pad and a good book after lunch or climb into the hammock strung between two trees. And then there is the wildlife.

The sounds, smells, spore, scat and sighting of animals that remind us that we are not in Kansas anymore! The “gnu” sound of the wildebeest that has earned him that nickname. A strange barking call of the zebra, which is so different from other equines. The chatter of monkeys in the trees. The whooping call of hyena as darkness falls. The laughing hippo as he crashes back into the river at 3AM waking me from a dead sleep. The deep roar of the lion from 5 miles away that sends chills up my spine and the distinctive chuff of the leopard near camp followed by the warning bark of the baboon as he alerts his tribe to climb to safety. The birds chattering in the trees, flying overhead, begging for food from their parents or scolding us for disturbing them.

We are never far from that which makes the Mara so unique. Sleeping in a tented camp our senses are constantly filled with its majesty and mystery: Sitting by the campfire with drinks and hors d’oeurvres before dinner… entertained by Masai who appear out of the darkness to sing, laugh and dance in the firelight and then leave just as mysteriously into the pitch darkness of the night. Exposed to the wonder of the land with guides, grooms, tent staff, dining staff, night guards that love this land and want us to come away with memories that will last a lifetime.

Having been for three safaris to the Mara it feels like coming home when I arrive. The staff knows all the returnees by name. They smile so broadly I can’t help but acknowledge that they meant it when they said we were part of their family after the first safari. The feeling is genuine and honest and is more like family than when I am around my own flesh and blood. These people have so little, but they live so fully it makes me wonder how we call the existence we have in “modern” society modern. Unspoken is the commitment each of the crew has to their tribe and extended family that they return to at the end of the safari season. Some are tribal chiefs and support a whole village on what they earn. Others are third generation crew for Safaris Unlimited, which was started by Gordie’s dad, Tony, 40 years ago.

So much can happen in nine days that it feels like a lifetime. At the end of each day, sitting around the campfire, reminiscing about the game we saw, looking at photos from the morning ride it is hard to believe that so much life could be packed into 24 hours. At home I still see many of the people that have gone with me. We continue to talk about the trip from four years ago and they have photos ever present on their computer, phones and iPads to remind them daily of the adventure.

Now having taken 3 groups on horseback safari to the Masai Mara there is one thing I know. The Mara knows what you need and gives you that gift. You may not know why you go. You may never return. But you will never forget the experience of riding through the dawn across a plain that goes on as far as the eye can see, unencumbered by the trappings of modern life, galloping with the game. And you will be forever changed by the experience.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.64