Story and Photos by A.J. Mangum

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.75

Argentine rawhide braiders Pablo Lozano and Armando Deferrari are ambassadors for their art form

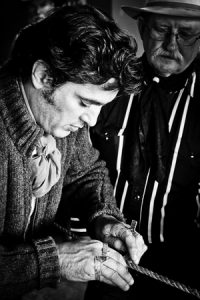

It’s a chilly spring morning in Salmon, Idaho. The sky is overcast and the Beaverhead Range sports a fresh dusting of snow. Inside a basement classroom of the Sacajawea Center, a community venue on the edge of town, Argentine rawhide braider Pablo Lozano stands surrounded by students as he slowly demonstrates a braiding technique, exaggerating each movement of his hands as his fellow craftsmen lean in close so as not to miss the slightest detail.

“Here,” he says, demanding the students’ attention. His hands cross, and loose strands of rawhide begin to form the suggestion of an emerging pattern. “Over one. Under two. Over one. Under two.” The students work to copy Pablo’s technique, their gazes shifting from their own work to the example held by their instructor.

The weeklong workshop, organized by Salmon saddlemaker, silversmith and rawhide braider Jeff Minor, has drawn 15 students from across the inland Northwest, and from as far away as Germany, to learn braiding techniques from Lozano and his compatriot, fellow Argentine braider Armando Deferrari, both members of the Traditional Cowboy Arts Association. Minor became acquainted with the two master craftsmen in 2004, when the Argentines taught a TCAA workshop at Oklahoma City’s National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Minor subsequently traveled to Argentina for further instruction from the pair.

“I was fascinated by their take,” Minor recalls. “The gauchos have a distinct horse culture, but it’s similar to the cowboy culture in that we’re both working with rawhide and producing something useful. Pablo and Armando want to educate people and keep this tradition alive, which is the same thing I want to see happen here in North America.”

Argentine braiding is often defined by finely cut strings, uncompromising utility, and complex rawhide knots rarely seen north of the equator. That combination of traits has, in recent years, drawn unprecedented interest from North American braiders, a demand that’s been largely met by Lozano and Deferrari’s educational efforts; in addition to workshops in Salmon and Oklahoma City, the two have taught braiding in Boise and Elko. The Argentine influence has, arguably, helped elevate the artistry of American braiding, with leading craftsmen like TCAA members Nate Wald and Leland Hensley occasionally incorporating Argentine techniques into their work.

“Some of the techniques we share might once have been more common in the United States,” Deferrari explains, “but could have been lost because master craftsmen might not have communicated them to younger braiders.”

Lozano and Deferrari say that their experiences teaching in the American West often amount to cultural exchanges, as they return to Argentina’s gaucho country with new insight gleaned from their cowboy counterparts.

“There’s often a trading of techniques and ideas, in particular with the preparation of cow hide,” Lozano says. “In Argentina, it’s not so common to use cow hide the way it’s used in North America. We use softened cow hide, but rely more on horse rawhide.” Rawhide made from horse, he explains, has a tensile strength that allows for the delicate strings and intricate patterns for which Argentine braiding is known.

Rawhide holds a special place of reverence in the gaucho culture, in which braiding is regarded as nothing short of an art form. Even the raw materials command great respect, as artisans study hides intently to uncover creative possibilities.

“Pablo says the rawhide speaks to him, and tells him what to do with it,” says Terri Berthelsen, a braider from Baker City, Oregon, and a student in the Salmon workshop. “He has a different understanding than most people. He can look at a hide and determine if it should be used for a set of reins, a bosal, a fine piece of fib work. That takes a lot of time and experience.”

To the uninitiated, rawhide braiding is a craft full of mystery and esoteric practices. On one afternoon, midway through the workshop, Minor arrives with a fresh horse hide and Lozano and Deferrari study it, turning over the still-wet blanket of flesh to point out to students its unique characteristics, and to explain how it might best be utilized as working equipment. On another day, Lozano places a dry cow hide, hair side up, on a concrete slab outside the classroom. He sprinkles ash across the hide, then coaches students as they scrape broom handles across it. In a small act of magic, the ash loosens the hair, which pushes off in great clumps to be carried off by the bucketful, leaving a sheet of bare rawhide that resembles thick parchment.

Mysteries continue to unfold over the course of the week. Hides are softened by letting them soak overnight in a nearby stream. Sheets of rawhide are rolled into telescope-like tubes and lightly pounded with all manner of makeshift mallets, loosening taut fibers. Hides are softened by slathering them with beef tallow carefully prepared for this particular use.

Once hides have been adequately prepped, they’re cut into strips, which are then cut into thinner strips, finally forming strands that will be braided into recognizable tack — reins, bosals, hobbles, reatas. At each stage of preparation, the material has less and less to do with its grim origins, and moves one step closer to a new life, a new purpose, one that could be considered a tribute to the animal from which the hide was harvested.

As the workshop approaches its final hours, students fill the Sacajawea Center classroom, braiding at improvised workstations. Lozano and Deferrari offer feedback on their techniques, and finished products. Rawhide gear, Deferrari explains, should be durable and flexible, with tight knots and a good finish. He does not mention one additional attribute: Quality braided rawhide, it seems, also reflects a braider’s peace of mind; when a flaw is found in an experienced craftsman’s braiding, it’s often a sign of rushed work. And if braiding is anything, it’s an exercise in patience.

“That’s something Pablo and Armando are teaching us,” Berthelsen says. “You start cutting strings and you might get frustrated, or you get partway through a piece and a string might break. With this kind of work, you can’t worry about lost time.”

As their students learn new perspectives on the craft of rawhide braiding, Lozano and Deferrari emphasize that, while the techniques of this art form might vary by geography, common ground among its practitioners is easy to find.

“When I first traveled to the United States, I had no idea what to expect from the North American cowboy,” Lozano says. “I realized the cowboy and gaucho have a lot in common — their shared passion for the horse, and the vast areas they cover on horseback. And, despite the distance separating North America and Argentina, the cowboy and gaucho use similar tools to achieve the same goals.”

Interviews with Pablo Lozano and Armando Deferrari were conducted with the help of translator Domingo Hernandez. A.J. Mangum is a writer and photographer, and the editor of Ranch & Reata magazine. Learn more about TCAA workshops at www.tcowboyarts.org