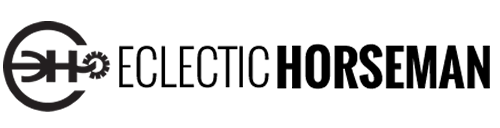

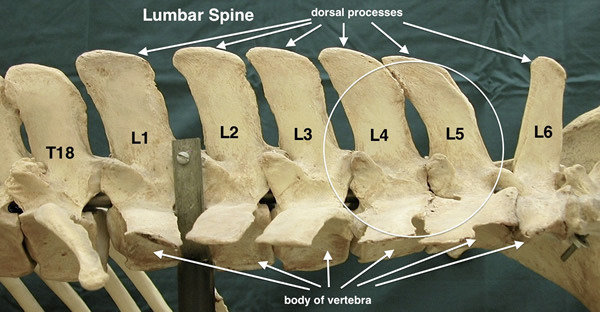

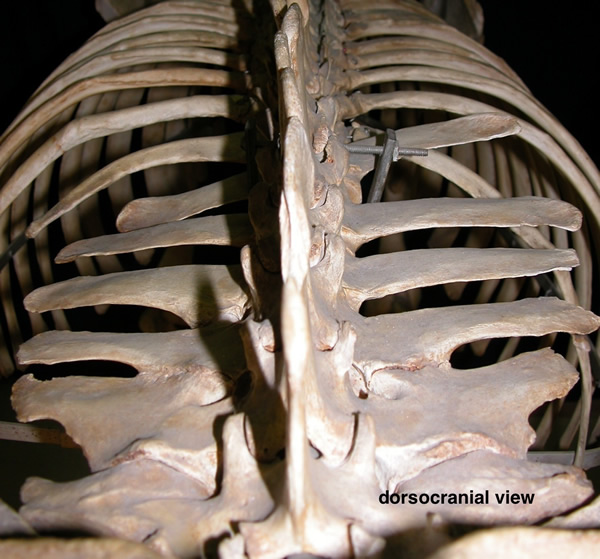

Next time you ride you might consider the hero of weightbearing, your lumbar spine. This segment, between the thoracic vertebrae (associated with ribs) and sacrum (which is part of the pelvis) bears the weight of your body allowing you to sit quietly on your horse yet has enough flexibility to follow his motion. (Photo 1.)

The word lumbar comes from latin lumbus meaning pretaining to the loins. This is not to be confused with lions who also have very powerful loins! (Photo 2.) The loin is the area between the ribs and pelvis on either side of the spine. Humans typically have five lumbar vertebrae whereas most horses have six. The equine exception is the Arabian who like you, has only five.

These 5 or 6 vertebrae do a big job. They support your body from above and transmit the forces generated from below in order to move you forward and upward. Since the horse rarely sits it is this second job that is critical to his good function when you ride. He has to flex his lumbar spine for engagment of the hindquarters and stablize to transmit the force from his hind feet to his head while supporting your weight on his back. Depending on the position of lumbar vertebrae (flexion or extension) the horse can bear your weight easily or be in significant stress.

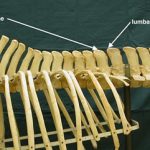

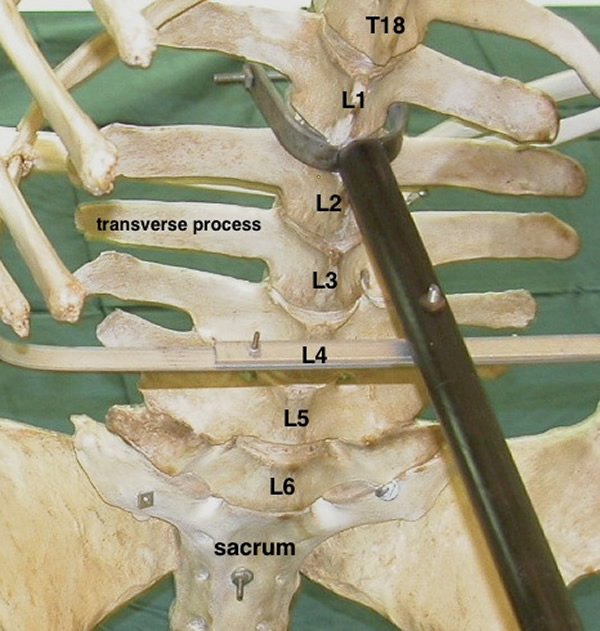

The overall size of the lumbar spine is different between horses and humans, but the shape and function is very similar. The lumbar vertebral bodies are quite thick and solid in comparison to the other vertebrae. In humans the cervical (neck) vertebrae are very small relative to the lumbar but that’s because your head sits on top of your spine. The horse’s neck is proportionately about one third of the horse’s overall length. His cervicals are much larger that the lumbar vertebrae in order to support the head weight of his head hanging 3 ft. away from his body. The lumbar are of significant size in relation to the remainder of his spine and have extremely large transverse (lateral) processes like air plane propellers. Given the shape of these vertebrae their movement is quite limited, which is a good thing!

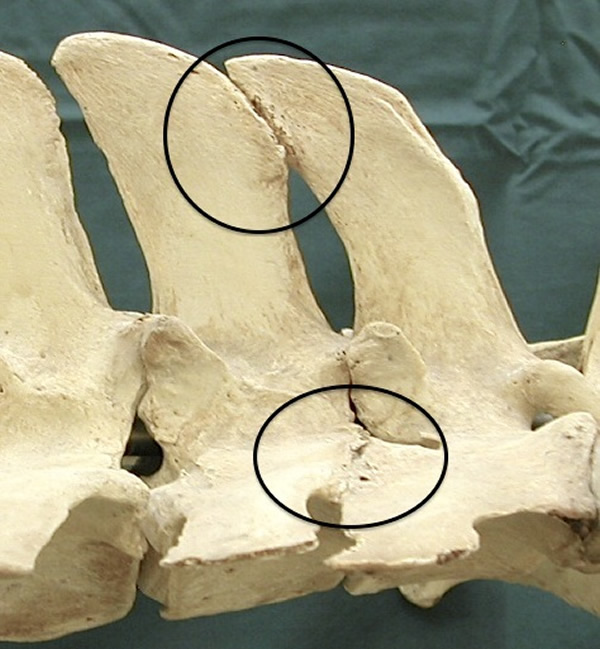

We generally think of the spine as something that should move, but it also needs to limit movement. Too much mobility between the vertebrae and nerves can get pinched or the dorsal processes rub could together, a serious problem called “kissing spines”. Therefore while the joints need the potential to move (hence the reason for chiropractics) they also need to be stablized in order to prevent damage. If you get the chance to assemble a skeleton put the lumbar vertebrae together. When you look at and feel the shape of the vertebrae this idea of limiting movement becomes apparent. You will quickly realize that side bending and rotation are almost non-existant, leaving flexion and extension as the primary movements of the lower back.

The possible directions of movement are easy to see when you look at the lumbar spine as a whole. The transverse processes are like two paddles in a row boat and much broader medially (toward the middle). The ability to decrease the distance between the them necessary for side bending extremely small. The facets (joints between the vertebrae) are a bit like lincoln logs locking the verterae together. This keeps them very upright and prevents rotation. Extension is limited by the dorsal processes. Photo xx shows how they were rubbing together in this race horse. This must have been painful! In flexion the dorsal processes will get further apart as the underside of the spine comes closer together. This happens when the horse engages the pelvis and rounds the lower back for example, just before a jump.

To get a sense of how the lumbar vertebrae join make two fists and place them so that the knuckles are interlocking and your thumbs out to the side facing you (photo). Keep the knuckles together and try to rotate one fist in relation to the other. Feel how the design of your knuckles prevents you from doing this. Try to side bend on the thumb side of your fists. You won’t go very far before your thumbs touch each other. Extend your fists at the knuckle joints by raising your elbows. You will move much farther than your lumbar vertebrae because there are no dorsal processes to stop you. Flex your fists by lowering your elbows. Notice it is quite easy to move in this direction. Your knuckles will come apart allowing you can go much further than an actual spine.

While the shape of the vertebrae is similar between us the overall shape of the lumbar area is quite different. Unlike the horse your lumbar spine has a forward curve (lordosis) which formed after birth. When you were newborn this part of your spine was rounded (kyphosis) more like the horse. In the process of learning to look up as a infant you developed the forward curve necessary for standing. This curve increases the strength of your spine without having to add more bone or muscle. When sitting, if you allow your back muscles to relax, the curve will decrease slightly giving your lower back a flat appearance. Don’t worry the curves are still there, just slightly less. As the muscles decontract they become more full, which is why your back feels flat. This flattening is very important for allowing your hips to have enough freedom of movement to absorb your horse’s motion in sitting trot and canter

The horse’s lumbar spine is quite straight and better designed for flexion than yours.. It is interesting to note how the dorsal process of the sixth lumbar vertebra is at a different angle than the preceding five which aim forward towards the horse’s head. The sixth is much more upright. The joint between this vertebra and the sacrum have significantly more capacity for flexion than we have in our lumbrosacral joints, which aids him in flexing the lower back and engaging the pelvis for collection in dressage or jumping.

Your lumbar spine bears weight from above because you are bi-pedal (standing on two legs). This loin is considered “weak” in the horse as far as weight bearing is concerned because there aren’t any ribs to support a downward force. If the horse stood on his hind legs all the time the lumbar area would be similarly positioned to yours, supporting the weight of his upper body. Instead he spends most of his time in a horizontal frame. Weight from above would be like you getting on all fours and having someone sit on your lower back behind the last rib. I don’t think you would last very long before crumpling under the weight and this is why saddle fit is so important.

It is critical that there is no pressure of any kind on the horse’s lumbar area for good function. If the saddle goes beyond the ribs and sits or presses into the lumbar area it will adversely affect the horse’s ability to flex his lower back correctly. When the horse goes into extension due to poor saddle fit, discomfort or pain he will have difficulty bringing his pelvis underneath him or lifting his back. This doesn’t mean the occasional bareback ride tandem with your friend will hurt him but chronic pressure on the lower back will definitely do some damage. If you want your horse to perform properly in sporting events he needs to be free of any pressure points which would cause him to tense the lower back muscles and extend the lumbar vertebrae.

In addition to pressure from above, improper shoeing or poor foot balance will affect the lumbar area. If your horse is struggling with long toes and low heels it will pull all the way to up the back of his leg to the lower back creating stress. This will also prevent him from engaging the pelvis. A long toe is like walking around all the time in swim fins on dry land. Try it some time and feel what happens. How much harder do your lower back muscles have to work in order to drag the fins forward? The effort of moving over the long toe can strain the lower back area especially if the horse is poorly muscled over the loins or fatigued. A shorter break over allow the foot to come through more quickly and takes less effort so that the hoof can land further under horse’s body.

Next time you ride take a look at your horse’s loin area. Are the muscles full and soft or tense and hard? Do you hollow your lower back when you ride or let your lower back flatten and lengthen? How does your horse respond to this change in your position? Experiment and see if your horse lets go in the lower back when you do.