Written by Heather Smith Thomas

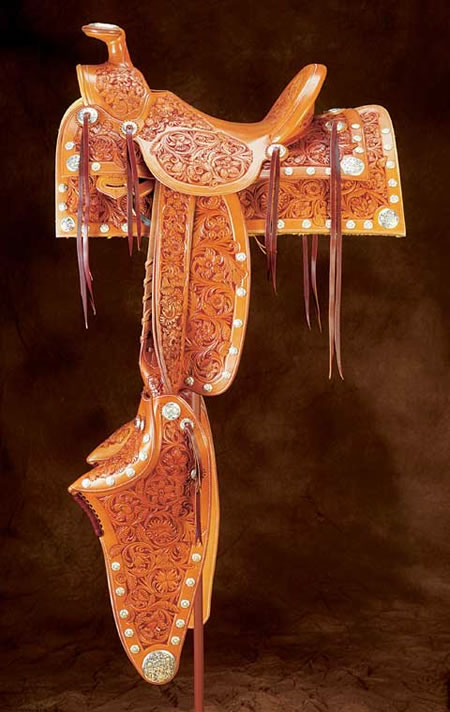

There are many good saddlemakers/ craftsmen who create superior western tack. Cowboy gear has become an art form in recent decades, but there must always be a connection between art and function. Cary Schwarz, a saddlemaker in Salmon, Idaho, says most people tend to compartmentalize and separate things so we can easily define them, but it’s never that simple. “What I try to do in my work—whether it’s a saddle or any other kind of gear—is balance both art and function. Art is an important aspect of even a very plain saddle.” People want their tack to be pleasing and look nice.

“When it comes to something that we consider pure function, like the shape of the seat—which determines comfort and balance for the person riding—it’s still sculpture. When you say the word sculpture, the first thing people think about is art. And it is. You are literally shaping the seat, yet what you are primarily looking for is not so much aesthetics, but function. Art has a lot to do with the way things fit. The parts and pieces of a saddle should fit together nicely. They function nicely when they fit, and also look well when they fit,” he explains.

He considers himself artistically bent. “The art part of working with leather has been the easiest part, for me. When people take a lot of pride in their horses and horsemanship, they typically take a lot of pride in their equipment as well. They want something that has that kind of balance—something that works really well but also looks good,” says Schwarz.

“Rather than a threshold you cross from art to function, or from function to art, from one side to the other, I regard it more in a seamless fashion. It’s more of a holistic approach to the craft, to not forsake one for the other. Sometimes, however, depending on what use the saddle may have, we might tip the scale one way or the other. The craftsmanship of saddlemaking and leather working is constantly making judgment calls. You want to have an eye toward the final product and what use it would have, and then you place these various elements on the scale and make an evaluation,” he explains.

Something a rider might be using 10 hours a day, day after day, might need to be simple rather than so ornate that it might be uncomfortable. And something as basic as the thickness of leather might depend on its use. For something you know will be used hard every day you might choose thicker leather, to give longer wear. If it’s not going to be used that hard you could scale back on leather thickness. The saddlemaker is constantly making judgments.

“This is a thoughtful approach to craftsmanship, rather than just grabbing some leather, nails and a hammer and hoping that by the end of the day you’ve produced a whole bunch of product—that you could turn out even if you were half asleep. Horsemanship is similar. There are some people who are merely passengers on a horse, and others who are aware completely—every moment they are on that horse. Leatherwork can be a passive activity or an active one. If it’s an active one, you are always thinking about what you are doing, every moment. When you have that kind of process, there is tremendous opportunity for refinement and improvement,” he explains.

“With me, it’s become a bit of an addiction. Rather than cranking out a lot of products that are pretty much the same (which I feel would become very boring), I want to create something unique. I enjoy being challenged artistically as well as with regard to the function of things,” he says. He always tries to more perfectly custom tailor his work for what it will be used for, regarding what each person wants.

“With me, it’s become a bit of an addiction. Rather than cranking out a lot of products that are pretty much the same (which I feel would become very boring), I want to create something unique. I enjoy being challenged artistically as well as with regard to the function of things,” he says. He always tries to more perfectly custom tailor his work for what it will be used for, regarding what each person wants.

“Sometimes you have to try to read into what they’re trying to say about what they want. When people come to me to have a saddle made, there’s usually already a certain amount of trust—that I will make those kinds of value judgments. I get basic information from them, and they pretty much trust me on the rest of it,” says Schwarz. They know the end product is something they will be happy with.

Saddles have a unique combination of function and art. “Building a saddle is quite demanding because of having to fit not only the horse, but the rider. It’s a much larger piece to work on than many of the simpler, smaller leather items. The molding of leather that’s required for a saddle is extensive,” he says.

“I’ve mentored a lot of students in crafting saddles. One fellow from Virginia came here a year and a half ago and still calls once in awhile to ask questions on a variety of things such as leather forming issues. Molding leather is one of those things that puts you into a whole different dimension than flatwork (like bridles, harness, etc. where there is very little molding). With flatwork you just put two pieces together and sew it up.”

Saddles present a unique opportunity, in many ways, for a greater challenge. “It’s a chance for artistic expression, but I say that at my own peril, because I’ve been thought of by some people as more of an artist than a saddlemaker. I am part of the TCAA (Traditional Cowboy Arts Association). They continually say that our show at the museum in Oklahoma City crosses that threshold into art. A big part of our mandate is that things be functional as well. It has to be something that you could go out and use, even though many of the items we create and show will never be used, just because people consider it so elaborate that they wouldn’t want to use it,” he says.

Schwarz also has horses and knows about horsemanship. He grew up on the family ranch near Kilgore, Idaho, and still rides when he gets a chance. This gives him a good feel for what a piece of equipment should be like. “I also get to use some of the things I make, but not nearly as much as I’d like. Number one, I’m a saddlemaker and I do not consider myself a cowboy—though we’ve run cattle and still have a ranch. I also packed and guided in the Selway years ago,” he says.

He knows the importance of function, but over the past several years has come to understand that some of the great saddlemakers of the past were not horsemen at all. “They were just good at catering to the needs of their clients, and they learned about function through an apprenticeship program from someone else. Being a horseman can be a selling point, however. When people know that their saddlemaker is also a horseman (albeit a struggling part-time horseman like I am), they tend to trust you more.”

Yet if you learn from the right people, he feels that being a horseman is not a necessity for good saddlemaking—even though it’s important to many customers. “I can’t begin to count the times people have asked me if I had horses, and whether I ride. In their mind, this makes a difference. That’s OK, but I still maintain that someone who hooks onto the right information could probably make as good if not better saddles than the person who is in the saddle a lot. There are other factors involved, and even though being a horseman carries a lot of weight with clients I think it matters more who you learn from and how you put it all together,” he says.

Always Learning

Cary Schwarz attended a trade school for saddlemaking in Spokane, Washington, and made his first saddle in 1982. Early inspiration and influence on his work came from Ray Holes Saddle Company, “Chas” Weldon and Dale Harwood.

Cary Schwarz attended a trade school for saddlemaking in Spokane, Washington, and made his first saddle in 1982. Early inspiration and influence on his work came from Ray Holes Saddle Company, “Chas” Weldon and Dale Harwood.

“I bought out Joe Hoover (a saddlemaker in Salmon, Idaho) in 1984. But I actually started out in a holster shop in Twin Falls, Idaho, in 1979. Before that, the Christmas of 1971, my parents gave me a Tandy leather kit when I was 12 years old.” He was always interested in leatherwork and had done quite a bit before he got that first job in 1979.

“I had no idea that I would do this for a living until I was well into my 20’s. I had a distant cousin who worked in the holster shop in Twin Falls and we had a common interest in leatherwork. He helped me get a job there, that summer. When I first stepped into that holster shop and looked at all those tools, and the people who worked there, I thought they were the most privileged people I’d ever seen. They got to work with leather and all those tools and equipment. They had the gratification of building useful things, and got paid for it! Lightning struck, and the next thing I knew, I had a job there, too, and I just loved it. That summer was a defining moment; I still remember my first visit to that holster shop 30 years ago, and how it made me feel,” says Schwarz. He always looked forward to going to work, and still does.

About 5 years ago, after building saddles for more than 20 years, he thought he had the major leaps of improvements behind him. “I figured from that point on I’d have to satisfy myself with incremental improvements and fine-tuning. Then I asked Chuck Stormes for a critique of my work. Chuck is a friend and saddlemaker who is like an institution in Canada, near Calgary. He gave me a critique and was very honest. I got bruised up a bit, but his critique was not mean; it was just honest. I went up there on two different occasions and spent several days with him, and he was extremely helpful.”

After that mentoring, Schwarz has had people tell him that his work just keeps getting better. “I have to credit Chuck and his critique, and the time he spent with me. That was very instrumental—at a point in my career where I very easily could have just coasted. I was being exhibited with the TCAA at the cowboy museum. I could have felt pretty good about how things were going, but I wasn’t really satisfied. Chuck and his critique came along at a very opportune time,” says Schwarz.

“First and foremost, for anyone, at whatever level you are (even if you’ve spent 50 years at something), you can always learn more. We tend to give that cliché a lot of lip service, but there aren’t a lot of people who are really trying to improve. It’s a lot easier to sit back and say I feel pretty good about what I am doing, and why go to the extra trouble and effort to take things to the next level.”

A leather stamping toolmaker once said to Schwarz that most people end their learning at about 55 years of age. “That’s a broad generalization, because some seem to end their learning experience at age 20 and others are always learning. I feel I am more of a student than a master. Thinking of yourself as a master at anything can really get in your way of learning anything new. This often trips people up. Even if they don’t seem to have a big ego, it’s the personal pride that we are all hard-wired for, and this can be a real barrier to learning,” he says.

“The first thing that has to take place, in order to learn something, is recognizing that you are limited. Then you’re open to opportunities for learning experiences. When I get to thinking otherwise, I try to lurch back to the place where I am the student, not the master. If I have achieved any level of success it’s because I’ve been a student of the craft. The more I learn, the more I realize there are more layers of information I haven’t accessed yet. If you can keep your ego in check you find out how little you really know!” The challenge is to stay open, and keep learning.

His most recent learning experience was a 2-week visit to France this past spring, learning from European craftsmen. “It’s always interesting to learn from other cultures, in more ways than you can imagine. I have always been fascinated with Old World craftsmanship and leather case-making techniques—how to mold, shape, and hand-sew different types of joints. I’ve always tried to work the British angle, however, because of the language. Europe has many craftsmen a person could learn from, but either I needed a handle on their language or they mine, and this was a barrier,” says Schwarz.

A friend of his in the TCAA, Pedro Pedrini, a saddlemaker born in France in the early 1950’s and who came to the U.S. in 1978 for the first time, is an excellent craftsman and was acquainted with Jean-Luc Parisot, a Frenchman who makes English style saddles. “He’s been making saddles in France for 31 years as a civilian employee for the military, building their saddles. Horsemanship is still a part of their military and mandatory for officer training. Pedro and I went over there this spring to learn some hand sewing techniques and refine some fundamentals about edge finishing and all the case-making methods, as well as some of the different styles of bridlery and flatwork. Almost everything Jean-Luc does in that shop is hand sewn. Any really well-made English saddle is all hand sewn,” explains Schwarz.

“We learned those things and got a heavy dose of French culture along with it. Just as importantly, I came back with a deeper understanding of craftsmanship. This was a once-in-a-lifetime experience and I feel I will be learning from that experience for a long time yet,” he says.

“When word got out that we were coming over there, some other people Pedro was acquainted with, who make western saddles in France, wanted us to spend a couple days with them. We ended up teaching a 2-day class on flower stamping. We were over there to learn, and also taught this class. There were 7 Frenchmen and 2 Spaniards in the class. Though this was a language barrier, every time I spoke, my friend interpreted for me. It worked very well because he also co-taught the class and knew what I was talking about, rather than just being an interpreter. We had good feedback from them and they want us to come back next year, but that probably won’t happen. We were on a TCAA scholarship this year that made it possible, and next time I’d be on my own and it would be harder to pull it off. But that whole experience was the latest boost in my craftsmanship and saddlemaking.”

Schwarz’s work has been exhibited at the “Gathering of Gear” at the Cowboy Poetry Gathering (Elko, Nevada), and the Sun Valley Center for the Arts (Sun Valley, Idaho), the “Trappings of the West” (Flagstaff, Arizona), and “Trappings of Texas” in Alpine. His work also appeared in the National Cowboy Hall of Fame inaugural TCAA show in 1999.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.50