Written by Sylvana Smith

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.7

A new tack catalog arrived in the mail today. More than 100 pages, filled with bridles, bits and reins… halters, lead shanks, cross-ties and trailer ties… martingales, sidereins, and cavessons… a smorgasbord of devices designed to hold, tie, push, pull, restrain, shape, whack, scare, and otherwise operate our horses through physical contact.

A new tack catalog arrived in the mail today. More than 100 pages, filled with bridles, bits and reins… halters, lead shanks, cross-ties and trailer ties… martingales, sidereins, and cavessons… a smorgasbord of devices designed to hold, tie, push, pull, restrain, shape, whack, scare, and otherwise operate our horses through physical contact.

Any compassionate horseman can look through the catalog and quickly dismiss the devices that conceal horsemanship problems (the tie-downs and gogues, for instance), dismiss those designed as training shortcuts (there go your side reins and constricting halters), and dismiss those designed to cause discomfort or fear (so long, mechanical hackamores and twisted wire snaffles). Of the remaining devices—the simple snaffles, plain halters, and such—we can satisfy ourselves that with faithful attention to technique and feel we can use these aids in a way that is harmonious with the horse.

Yet when we watch our horses in the field, it’s clear that they are capable of operating on a much higher level than physical signals. Sure, they sometimes kick, bite, and bump each other… but more frequently, they effect change through non-physical, non-verbal communication. A look, a body attitude, an advancement, a retreat, an expression.

Consider one tiny detail of this 1000-lb animal—his ears. The ears communicate clear messages to other horses when they are pinned back hard, flipped cheerfully forward, set hard forward at attention, or flicked back on one side only. With a few ounces of non-contact expression, the horse can signal other horses to move away, come toward, move with him, or invite another horse in.

Watch what happens when a group of horses is grazing contentedly, and one horse suddenly picks up his head and adopts an energy-charged, rigid stance, eyes focused on the distance. The rest of the herd suddenly stops grazing, comes to life, and adopts his energy, readiness, and posture. Imagine the power of harnessing that level of awareness to communicate between horse and human.

“Ray Hunt talks about ‘harmony,’ Tom Dorrance talks about ‘unity.’ It’s a feeling of oneness that you share with the horse that’s like nothing else,” said Bill Scott. This North Carolina horseman has developed a program to help riders attain the connection he describes as “one rider, one horse, one mind.”

“This is not a connection reliant on physical contact or direct actions. It’s not a response offered to avoid some negative consequence. It’s the horse following your focus, feeling for your feel, trying to willingly search for what you’re visualizing,” Bill says.

“We are not taught to interact with the horse this way, so we don’t typically go into the relationship with the horse looking for this thing,” Bill notes. “Tradition has it that we ride a horse totally through a direct feel of some sort, whether pushing here or pulling there or whatever.” As we progress in our skill, feel, and timing as riders, we refine those direct actions so they become very subtle, but Bill advocates a lighter level of communication yet possible through mental connection.

Humans are often handicapped in this regard because our harried, mechanized society has stripped us of much of the awareness that should be innate to humans, and is still innate to horses.

“Society has conditioned us to be able to function with a lack of awareness,” Bill notes. “People can go from their air-conditioned offices to their air-conditioned cars, talk on the cell phone with the windows rolled up, go to the grocery store and be oblivious to the five people who are trying to get around their shopping cart blocking the aisle.”

“If we can tap into our inner presence—become aware on that deeper level and use it in our horsemanship—we have a powerful means to influence the horse in a way that is natural to him, Bill says.”

In fact, we’re already doing it, for better or for worse. We see it with the nervous showmanship competitor who can’t get his horse to stand still, (“he always does fine at home”). It’s in the showring hunter who travels quietly in a group at clinics but rushes around the rail in under-saddle classes, or the event horse that refuses the one fence that worried his rider on the course walk. Clearly, we already influence our horses by what comes from inside us. Why not exploit that awareness in our favor?

I confess, I had a hard time picturing this concept until I rode Bill’s horse. I was sure that every allegedly mental signal really worked because of some subtle physical manifestation. And I believed my horse was as soft and light as it could get—a willing response to a feather-light signal. Bill’s horse “Abe” showed me a whole different level. At first I thought of Abe’s difference as a terrific recipe of soft-and-willing (which I figured I had), plus an extra measure of life (producing a cleaner, faster response). I now realize that the extra measure was more than just alertness or energy, and rather the horse meeting me in the middle—a convergence of minds. As I was seeking to him, he was seeking to me. The end result is that our ideas came together faster and more accurately, not just with more life.

Sure, we can achieve fast, crisp response through easier yet dastardly means, if we wish. If the negative consequences are fearful enough, the horse will come together with our ideas pretty darned quick. Why not take the easy way?

“This partnership that you share with your horse should be a willing thing,” Bill says. “In any relationship, the ideal condition is where each of you wants the same thing. That’s not always a reality, probably. But if you can build a relationship so that each one of you is willing to do things for the other, it will always be a good relationship.

“My wife may ask me to weed-eat the yard. That may not be what I want to do, but I am willing. If she came out and threatened me with a big stick, the yard would get trimmed, but the relationship would suffer. This idea of a willing relationship is no different from what Ray or Buck talk about, but it’s one thing I think people miss the most out of it.”

How do we influence the horse then if not by direct feel?

Where “direct feel” is something you have at the end of the rope, Tom Dorrance refers to the “indirect feel,” where the horse is reaching for an intangible place of agreement rather than moving away from pressure. But how do you offer a feel if you don’t have some direct communication line?

Visualization. “Most everybody acknowledges that horses can sense fear or confidence, or tell the difference between aggression versus assertion,” Bill says. “Then why wouldn’t they be able to feel your focus? I know they can.”

That means the first cue you offer is simply visualizing what you want the horse to do. Not just a vague idea, but a plan with some clarity. Not just, “I want him to move off,” but “I want him to step first with his inside hind to move left at a workmanlike walk.” You can only influence the outcome if you know what that outcome should be.

“If the horse is trying to follow my focus, he’s reaching for the feel, rather than if I pick up the rein and he’s moving away from pressure,” Bill said. “I put my focus, that line out there and the horse is reaching and feeling to stay on that line, rather than me having to push him back on that line. You can do this somewhat with direct feel, but it’s the lightest with indirect feel.”

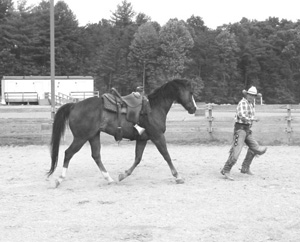

Energy. Horses feel our energy level and respond to it. “When people are working horses in the round pen, I often see one extreme or another: the horse that doesn’t want to go, or the horse that doesn’t want to slow down,” Bill said. “I see both of these scenarios often, and they’re really both the same thing. It comes from within.” The horse won’t go for the person who is standing there with no energy, and won’t slow down for the person whose movements carry tense, nervous energy.

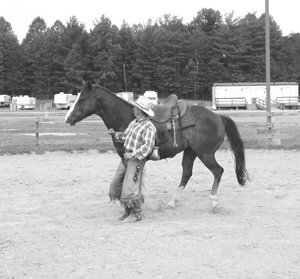

Body attitude. Your body attitude—upright or slouched, relaxed or tense, facing the horse or sideways to him, rigid or fluid, eyes soft or hard, motions smooth or jerky—communicate volumes to the horse. You can bring up the life in your body to move him off, let the air out and soften your posture to draw him in. You can invite him with smooth, fluid attitude and movements, drive him away sharply with crisp, insistent movements and body position.

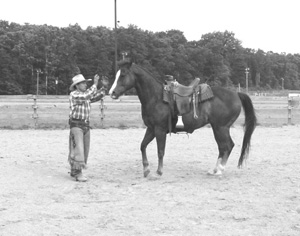

Hands. Your hands and arms can reposition or signal a horse by either leading or driving. A leading hand sweeping forward from the horse’s shoulder invites him to move forward. A driving hand pointed or waved at his hip asks him to move off or step across. A finger pointed toward his eye can push him away to change eyes and ‘pick you up’ with the other eye. A hand drawing in toward your body can draw him back to you after changing eyes.

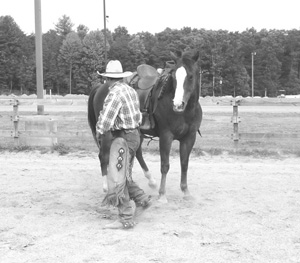

Body position relative to the horse. When the horse is traveling around the round pen, for instance, you can align your body toward his shoulder to slow or stop him, or toward his haunches to encourage him on. You can step sideways toward his haunches to encourage him to disengage behind, toward his shoulder to get the front end to step over, or almost hide behind him to draw him off the rail. The horse will follow the feel of your location, and you can adjust from moment to moment to shape up the movement.

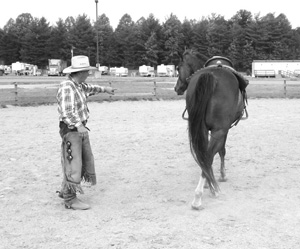

Advance or retreat. Combining body attitude and position, you can advance toward him with energy to ask him to move off, and back away with relaxation to draw him to you. These simple non-physical cues persuade the horse to willingly be with you, to ‘hook on.’

“The very simplest mental connection we get working is when a horse draws to you in the round pen,” Bill says. “That’s often the first time we notice him reaching for a feel rather than moving away from pressure. Most everybody gets a real feeling of elation the first time or two they do that. I’ve had people cry.”

Bill compares the connection with a ‘hooked-on’ horse to playing with bubbles. Dip the little stick with the ring into the bottle of bubble stuff. Blow a bubble, then another. You can use one bubble to catch the other bubble. You can push the second bubble and pull it, but if you move very fast and very hard without allowing the bubble to follow the feel, you burst the bubble, you lose the connection.

That bubble gets more resilient as your unity with the horse gets stronger. When you first explore drawing and hooking on with your horse, you can lose him if you move off too fast. Once he understands, you can trot off, switch back, and stop, and he’ll be right with you.

How do you initiate a mental connection with your horse?

The following guidelines will help you build connection with your horse, no matter what you’re doing—whether it’s targeted groundwork in a designated schooling session, or simply handling him around the barn.

Acknowledge that you’ll probably be starting with some physical cues. You’ll likely start the process by doing groundwork with physical, direct cues and having the horse move away from pressure. You do need some way—a halter rope, a lass rope, a round pen— to keep the horse from leaving before you’ve established the connection. You do, after all, need to have a way to ‘make the wrong thing difficult.’ Your progress won’t be very gratifying if the horse can find relief by leaving you, before he discovers that he can find relief as well by being with you.

Very quickly though, often in the first session, you can progress to doing the groundwork with no halter or rope. The secret to moving quickly from halter to halterless is to use indirect feel first for every request (visualization, focus, energy), and follow up with direct feel (feel on halter rope, swap with the tail of the halter rope, etc.) only if the indirect feel didn’t work. You’ll have the halter and rope available at first, but you’ll be steadily using them less and less, to the point where you can sling the halter rope over the horse’s neck and keep on working without physical connection.

For every request, clearly visualize what you want. Whether using direct feel or indirect feel—whether doing this with a totally green, unaware horse or a connected one—for every request every time… always have a picture in your mind of what you’re going to ask for and the end result.

“That’s the whole key to making this thing work,” Bill says. “It’s a thought process first, before anything else. I see it so many times where the only indication the horse has to change anything is some physical action: the reins, the kicking or whatever; there was never a picture in the person’s mind of what they wanted.”

Don’t just think, “I wanna canter,” but rather, “I will trot 10 steps and initiate a left-lead canter depart on the 10th step.” Not just “I want the horse to hook on,” but “I want him to come off the rail, step his inside hind across and in front of his outside hind, and face me, at that pole.” If we have muddy visualization, we can only develop muddy responses. The clearer you get with your plan, the clearer the horse gets with his answers.

“That’s also what keeps you from losing them,” Bill says. “Many of us get this connection working sometimes but not all the time, and that’s because we still don’t have a plan we can follow through with, and aren’t very specific with our requests.”

I certainly experienced this at a recent clinic, when I lost my allegedly connected horse to a pile of manure. It’s humbling to rank lower than a pile of manure in interest to your horse. But at the moment I lost him, I was basking in a side-by-side stroll with no real plan.

Reward the slightest try. This principle holds true in all our work, but it’s all the more critical when you’re trying to influence a horse without direct cues. Since the figurative ‘pressure’ is miniscule, compared to physical contact, the training relies more than ever on the horse searching toward release. You can go slow to go fast here, in a ‘warmer-warmer-colder-colder’ game where you reward tiny hints of compliance and adjust to head off tiny signs that something is going astray.

For instance, when you’re first asking the horse to hook on, you reward (retreat, soften) when the horse does nothing more than flick his inside ear back. Later, we’ll look for more, but we started by rewarding a seemingly trivial connect. Everybody who has experimented with hooking on has done this.

Carry that concept to other exercises. Look for and reward the first hint that things are going in the right direction. For instance, when asking the horse to back on mental connection, you might first reward something as simple as his weight shifting back, even though he didn’t lift a foot. When teaching him to take the forequarters across on a non-physical signal, you might first release him just for shifting the weight back, preparing for the movement. When teaching him to follow you with no lead line, you might first stroke and praise him for simply looking in your direction and reaching toward you with his neck as you moved away from him.

Follow up if necessary. Things may not work out exactly as you’re picturing. You may step in behind the horse to ask him to come off the round pen fence, and he doesn’t. You may turn around and find your buddy sniffing a pile of manure. You might want him to step the hindquarter over and he walks over you with his shoulder. You might have given him an opportunity to ‘soak,’ and instead he whinnies to his barn friends.

If you had a picture in your mind of what you wanted, you can adjust to fit the situation and keep shaping the horse toward that outcome. Start your ‘correction’ with the 1-2-3 progression of non-physical cues—visualize, focus, energize—but don’t be surprised or disappointed if you may have to add some different or direct follow-up.

For example, if the horse doesn’t understand that your energy, leading hand, and driving hand are saying “move,” you might have to follow up with a twirl of the halter rope or a verbal cue. If the horse’s attention drifts off, you might have to recapture it by slapping your hand on your chaps… or kicking up a little dust… slapping your rope against your leg… waggling your flag… or snapping your fingers.

Trust the horse. “One of the key things horses learn from us is whether we trust and believe in them,” Bill says. “Along with this mental picture you have to carry into this deal is the need to believe in your horse and believe in yourself.

“Even if I have it in my mind that I’m 100 percent sure that the horse is not going to understand this mental connection that we can share… he’s been taught to ignore any mental energy and focus; and I’m almost positive that it’s not going to work… I still always go there first.” If you don’t offer him the chance to follow a feel, he won’t make progress in that direction.

Be aware when you’re losing the horse’s attention, before you lose him. When you have a tangible connection to the horse—reins or rope—we can allow his attention to drift and still get him back anytime. After all, we have the rope; he can’t leave us. Not so when working the horse with no physical connection. We have to keep him with us mentally. That means being keenly aware of when we’re losing him.

The greater our awareness, the more this understanding will come from within. But at first, physical indicators will be key.

The horse’s inside ear is tipped in our direction, his body arc follows the shape of the circle he’s traveling, his strides are fluid and relaxed, his eye is soft and looking in our direction, he is stretching through his topline, he disengages the hindquarters by stepping through and in front with the inside hind… these are good signs that he is with us mentally.

Different story if you see a bulge where his jaw meets his neck, ears pinned or set hard in some other direction, head tipped away, neck up, back hollow, strides short and pinched, body arc bent away from the path of travel, hind leg stepping to but not through when disengaging the hindquarter. This horse is not mentally connected. He’s distracted, defensive, and keeping open his options to leave. Since you know what he’s thinking, you can shape it up your way before he ships out.

Trust him again. So, you trusted the horse, you took the halter off and started testing your connection, and he left you. What now? “That doesn’t necessarily mean you need to go and put the halter back on,” Bill says. Try it again. “Instead of saying, ‘Oops he left me, I better put that halter back on,’ move him around, get him hooked back on, and go from there.

“One of the most effective ways to bring back his attention is to move his feet,” Bill says, and you could do any of the things we described earlier for follow-up. “Any of these things are effective as long as you stop when you get the horse’s attention. You should be able to feel the horse coming back to you, without relying on physical cues.”

Why not just put the halter back on and go back a step? Bill feels we progress further in developing feel and awareness if we move out of our comfort zone and experiment. Doing the groundwork with no halter or rope really is different from having those aids in hand and believing you’re not using them. It’s quite a different experience, for horse and handler both—like the difference between riding on loose reins and pulling the bridle off altogether. Not the same at all.

What groundwork exercises can you do with no halter or rope?

Start simple and build on the foundation, naturally, but you should be able to do the full gamut of groundwork exercises we do in typical clinics, with no halter or lead. The difference is you’ll need greater awareness, and instead of direct contact you’ll rely on the indirect aids described earlier. For example:

• You’ll get the horse hooking on by visualizing what you want, advancing toward him with energy when he’s unconnected or ignoring you, retreating backward with passive body language when he’s starting to connect and draw toward you.

• Once hooked on, you could lead the horse around with no lead rope by believing that he will stay with you, adopting the right energy level in your body (enough to hold his attention and have a plan, not so much that you break the bubble), being fluid and inviting when he’s walking along with you, and snapping your fingers or slapping your hand on your leg when his attention wanders.

• You could disengage the hindquarters by visualizing the inside hind stepping across and in front of the outside hind, stepping toward his hindquarters, and perhaps pointing or waving your driving hand while keeping your leading hand (on his head side) close to your body.

• You can then ask him to drive off by picturing him marching off at a walk, picking up the life in your own body, opening up your leading hand, and waving or pointing your driving hand at his hindquarter.

• You can slow and stop him by picturing it, letting the air out of your body, slowing your stride, relaxing your hands by your sides, and slowing to a stop yourself.

• You could back the horse by picturing him shifting and then stepping back, standing in front of him and pointing at him, softening for an instant when he starts to shift his weight back, then pointing again or advancing toward him with positive energy.

• You could step the forequarters across by imagining the horse shifting his weight back, standing at his shoulder, pointing your fingers in an imaginary line toward his opposite hip, softening your posture and backing off for a second when he shifts his weight back, then picturing one foreleg stepping clearly across, then the other, following up with an upright body posture and pat at the air with open hands near his jaw.

• You could turn him toward you by visualizing the path you want him to take, and either drawing in his eye and pulling his front end toward you, or focusing on his hip and signaling his hind end to move away from you.

Without physical contact, you not only influence the horse to do something, but you can influence qualities or degrees of that movement. For instance, you can define:

• How deeply a horse bends or turns, by where you position your body relative to his.

• Whether the horse’s weight is forward or back, by where you signal with a driving hand, or where you stand relative to him..

• How fast he travels, by how much energy and activity you carry in your own body.

• Where he comes off the rail, by where he is when you retreat and invite him.

• How much or how many of anything, by how assertively you ask and when you reward.

“The key is the release,” Bill says, and he uses that familiar maxim to describe qualities that we wouldn’t customarily seek to develop without physical connection. Collection, for example. Driving around the round pen, the horse would likely be traveling along, relaxed, not collected at all. Position yourself toward the horse’s haunches, move him up a bit until he shows a little more engagement, and release him for that. Then build on that foundation, increasing the expectations each time, until the horse is volunteering collection without being physically held there at all.

“It’s a two-part thing that works off energy from inside you—the part that speeds that horse up and other part that gets the horse rounder, then the release, which is what he learns from.”

Why work a horse with no rope if we never have to do this in real life?

• To offer more to the horse on his terms.

• To honestly assess the degree to which our relationships are willing and voluntary.

• To improve our awareness, feel, and timing.

• To elevate our communication with the horse to a higher level.

“Once we have the horse really feeling back to us and responding to our feel, then all the other things that we have just enrich that vocabulary of communication with the horse,” Bill says. “For example, if I don’t have to pull on my reins to stop my horse and slow him down—I slow him down with my energy—then my reins are free for counter-bend, renvers, travers, all the more complicated maneuvers that I wouldn’t be able to do if he thought that when I picked up the reins I needed him to stop.

Even if we don’t need to do haute Ècole maneuvers with our horses, most everybody wants a lighter horse—a team-penning horse that operates like an extension of one’s legs and mind, a hunt horse that doesn’t pull our arms out on a full cry run, an event horse that lets his rider safely rebalance before fences, an equitation horse that responds to invisible cues.

We can achieve these things with direct feel—physical signals, falling back on mild coercion if necessary. But we advance our horsemanship to an even higher plane if we can achieve these things through indirect feel—a mental connection forged on equine voluntarism.

About Bill Scott

Growing up on a Georgia cattle ranch—the son of a university law department chair and a professor—naturally Bill Scott grew up with both an affinity for animals and an intellectual curiosity. As a result, he developed a horsemanship philosophy that melds the influences of Tom Dorrance, Ray Hunt, Buck Brannaman, Dave Seay, Chris Cox, Bob Loomis, Mike McIntyre, and others.

“Whether it was with dogs, horses, or cows, I always had the attraction to try to figure out this kinship we could have with animals,” Bill recalled. In 1976, a youthful quest for adventure took him out West, to a ranch in southwest Oregon. “There, I saw for the first time in my life some of these old buckaroos, like one mind operating the man and the horse. I was just a young buck who didn’t know what it was, but boy it looked good to me. I knew I wanted it.”

After college and farrier school, Bill got plenty of opportunity to explore those ideas as a professional farrier—frequently working with horses that others refused to shoe, and the ones that had never before been shod without sedation. After years of helping clients with these “special” horses, eventually folks got together and asked Bill to help them with other training issues. Ten years ago, these impromptu sessions evolved into an active schedule of clinics all over the southeast, and a training operation at home in Franklin, NC, with his wife, Leslie, and twin sons.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.7