*Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2017 in issue No.93 of Eclectic Horseman.

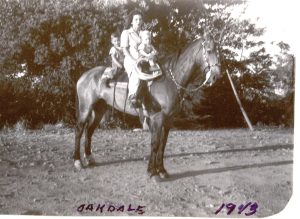

Gene Armstrong taught more than a generation of students with equine aspirations about farrier science and horsemanship at CalPoly (California Polytechnic State University) in San Luis Obispo, California, before retiring.

Even with such an abundance of equine teaching experience under his belt, Gene is one who considers himself a student of the horse to this day. At 74 years old*, Gene is still making bridle horses, teaching part-time at Feather River College in Quincy, California, as an associate professor, and shoeing horses.

“I think you have to work real hard at it,” Gene says about working with horses. “I’m not only thinking physically. I think you have to think about it mentally, too. In recent years, I’ve learned a lot by reading. Now I’m semi-retired. I still shoe horses and I ride three horses a day. I’ve got one six-year-old I’m bridling up, and I’ve got a two-year-old, and I just bought a long yearling—I fool with him each day. I usually shoe early in the morning if I’m going to shoe.”

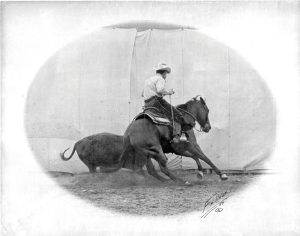

Gene can’t remember a time when horses weren’t a part of his life. His father ran ranches for other people in California and he grew up as a ranch kid.

“I didn’t get any formal [horse] training until I went to CalPoly university,” Gene says. “I was an animal husbandry major—or, animal science now. After that, I really never left CalPoly. I retired after 35 years…in ‘02. I taught a lot of the horse classes. Primarily when I went to work there, I taught farrier science and blacksmithing. I think the first colt class that I officially taught was in about ‘73. I went to work there in 1966. As time went on I got more involved with teaching horse production and colt starting and ranch horse projects and those sort of things.”

Early in his career as a professor, before he began teaching colt starting classes and other horsemanship courses, another professor at CalPoly, Gordon Baker, captivated Gene’s curiosity by talking about a guy he knew who was an amazing hand with horses.

“He knew Ray Hunt pretty well,” Gene says. “And he got to talking about this guy and so I couldn’t hardly stand it—I had to go visit him. He was in Merced [California] then, and so initially I was around Ray in the late ‘60s, and then it kind of went on from there. And then I probably was around Bill Dorrance more than Tom [Dorrance], but they were all a big influence on me.”

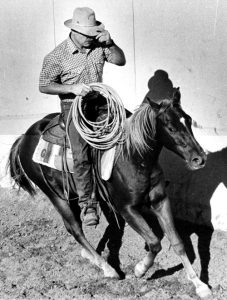

When Gene met Ray Hunt, Ray was in the business of starting horses. He hadn’t begun teaching clinics yet.

When Gene met Ray Hunt, Ray was in the business of starting horses. He hadn’t begun teaching clinics yet.

“I remember the first time I went over there,” Gene says. “He [Ray] just had a lot of youngsters—two-year-olds and three-year-olds—and worked them all in a round corral. I was really impressed with what he was getting done and how he was doing it. And it was pretty foreign to me, just the language, and I just wasn’t familiar with it—the process.”

Gene picked up on things from Ray, he says, and incorporated them into his teaching. But the farrier side of his work and teaching was as much a part of Gene’s career as horsemanship. He even makes his own shoes rather than using pre-manufactured ones.

“When I think about making a shoe,” he says, “there are so many more advantages to making a shoe over buying a shoe. One would be, you can select the iron for a specific horse. They could be the same weight of horse but some wear them out faster than others depending on the discipline. A big one would be just where the nail is placed and the size of the nail and the pitch of the nail. A lot of those things are not incorporated in a manufactured shoe. It’s more time consuming. A person has to have more skill, not that I’m the most skilled, I’m just saying for a person to learn it and be efficient at it takes a lot of skill.”

Gene now splits his teaching week at Feather River College between two days of farrier science and two days of riding with the students teaching horsemanship.

“It is a passion,” he says. “I guess it’s like anything that people get pleasure out of, no matter what you do it’s driven. When I was growing up people would say to a person, ‘You’re a good rider.’ This is my background being raised on a ranch—if you could ride and sit and be balanced then you knew something about riding. Well, I can’t disagree with that, but on the other hand, after I got off that thought and got real about riding then it just opened up a whole new door. It was just a big ol’ wide door that I realized that I didn’t know a lot about riding horses other than sitting on top of them. I think it takes quite awhile for people to get connected to that.”

Gene wonders when thinking about his father’s generation, which included the Dorrances, if people were more observant in some ways back then.

“It [a skill like farrier work or horsemanship] wasn’t just going to be handed to you or given to you,” Gene explains. “You had to develop a sense of observation and realize that other people made mistakes, they did good things…whatever with the horse.”

There’s a point in life that Gene talks about where people can transition from feeling like they know quite a bit to a realization that they don’t.

“Now I feel like as old as I am,” he says, “I feel like I learn something every day. But I’m kind of looking for it. I have to say very seriously, I had such an opportunity around a lot of good people. It’s pretty inspiring.”

So what advice does a seasoned professor of farrier science and horsemanship have for younger aspiring horsefolks today?

“I think people really need to know how horses learn,” Gene says. “It seems like what takes place in a lot of our work, especially in the competitive world, is things are done on a time limit and they’re done with probably more force than a horse can tolerate. Some of them tolerate it, some of them don’t. But I think when we talk about equilibrium in a horse and we talk about balance and we talk about other things, what do those tell us about the horse’s mind and how horses learn?

“A general concept of horsemanship is, and I believe this real deeply, that it’s not necessarily what the horse can do for me, it’s what I can do for the horse.”

Enjoy the article? Come to class and spend some time with Gene:

Eclectic Classroom – An Evening with Master Farrier and Horsemanship Professor Gene Armstrong