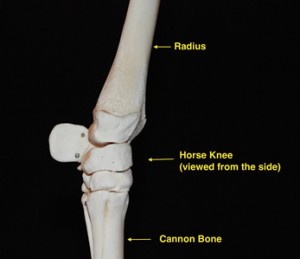

If I asked you to point to your horse’s knee where you would point? Most likely you would point at your horses’ front leg about halfway down, between the upper arm and cannon bone. This is the joint we call the knee in the horse.

Where would you point if I asked you to point to your knee? Most of you probably point to the joint in your leg about halfway down. But is this the same joint as the one you pointed to on your horse? Well let’s think about this for a minute.

Where would you point if I asked you to point to your knee? Most of you probably point to the joint in your leg about halfway down. But is this the same joint as the one you pointed to on your horse? Well let’s think about this for a minute.

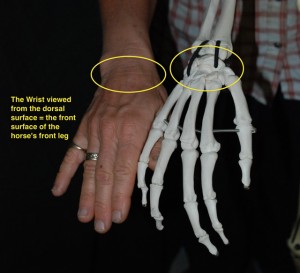

Remember that your horse’s front leg is the equivalent to your arm and his back leg is the equivalent of your leg. If you pointed to the knee on his front leg then it cannot possibly be the same joint as your knee, which is on your back leg. What then is your comparable part to the horse’s front knee? Why it’s the group of bones called the carpus.

The carpus is the joint in the horse corresponding to your wrist. The bones of the carpus are called carpal bones or carpi (pl.). This name comes from the Greek word karpos, which also means wrist.

The wrist in humans is a collection of 8 bones organized in two rows. The bones in the row closest to your body (proximal) are called scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform. The row further away from your body (distal) are called trapezium, trapezoid, capitate and hamate. While you may not be able to feel all 8 bones in your wrist you might be able to feel a few.

The wrist in humans is a collection of 8 bones organized in two rows. The bones in the row closest to your body (proximal) are called scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform. The row further away from your body (distal) are called trapezium, trapezoid, capitate and hamate. While you may not be able to feel all 8 bones in your wrist you might be able to feel a few.

Take your right hand and hold your left wrist. Identify where your wrist is by locating the two bumps that stick out to the sides at the end of your forearm. Place your thumb and index finger on the bumps. Slide your fingers towards your hand until your fingers slip into a groove. This is where your wrist bones are located. As you continue towards your hand the bones starts to widen out, you are leaving your wrist and heading into another grouping of bones we will discuss later

As you feel your wrist remember that there are 8 bones in this little groove so they can’t be very big. However they offer you the possibility of making a wide variety of movements with your hand like holding reins, writing or texting to your friends.

To feel the movement of your wrist hold it gently while you move your hand up, down, left and right. Make small movements and use your fingers to feel for the bones as you imagine the two rows. You may not be able to feel the individual bones but you should be able to feel the pisiform bone. This one is on the pinky side of the wrist. Gently experiment with the different movements of your wrist while you keep one finger on the pisiform bone. Notice that it seems to stay in place while your hand moves around it.

To feel the movement of your wrist hold it gently while you move your hand up, down, left and right. Make small movements and use your fingers to feel for the bones as you imagine the two rows. You may not be able to feel the individual bones but you should be able to feel the pisiform bone. This one is on the pinky side of the wrist. Gently experiment with the different movements of your wrist while you keep one finger on the pisiform bone. Notice that it seems to stay in place while your hand moves around it.

The design of our carpus gives us a lot more flexibility than the horse. The horse’s knee has to be a lot more predictable. It’s important for the horse’s knee to be able to withstand the weight of his body without buckling so that he can run and jump. But at the same time it has to be flexible so he can fold his legs up over a jump or lay down in his stall.

As the horse’s front leg travels out in front of him the knee unfolds and extends the hoof towards the ground. As the hoof meets the ground the knee must remain straight otherwise the horse’s front leg would buckle and he would fall down. You may have experienced a horse that did not get his front legs extended in front of him in time over a jump, like getting a leg caught in the polls. This is a very bad feeling! We take for granted that the horse is going to get his front legs without realizing it until things don’t work properly.

As the horse’s body weight travels over the front leg the knee must remain straight or extended so that the horse can use the front leg like a strut to support his body and aid in propulsion. After he has begun to pass over the hoof the knee will begin to bend making it easier to swing the front leg forward and repeat the cycle of movement.

Without a knee joint the horse would have to move the like someone on a pair of stilts. This would dramatically alter the horse’s movement. If you have ever seen a horse with a knee injury you can appreciate how important this joint is to the overall movement of the horse’ front leg.

On the other hand if the horse’s knee had the same amount of flexibility as our wrist it would be impossible for him to support a rider. Imagine if the horse’s knee allowed the lower leg to move sideways like our hand. You would never be sure that the hoof would land solidly on the ground to support your weight.

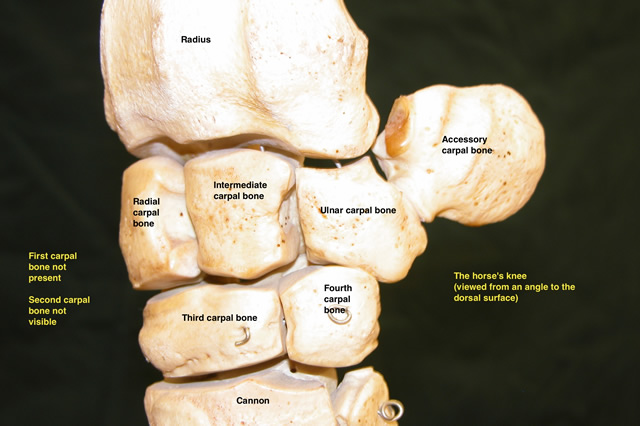

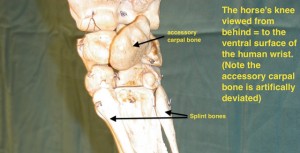

Even though the motion differs between the horse and human carpus the structure is remarkably similar. The horse’s carpus or knee is also made of 8 bones called the radial carpal bone, ulnar, middle, accessory, first, second, third and fourth carpal bones. Only 50% of horses have the first carpal bone. These bones are in two rows forming 3 joints. The accessory carpal bone is the equivalent of the human pisiform bone and can easily be identified.

Next time you are at the barn run your hand down your horse’s front leg stopping at the knee. Feel how flat the knee is on the front side. Now pick up his front leg and feel the way the knee flexes. You might be surprised at how wide the knee is. Remember that the 7 or 8 bones are organized in two rows, which explains the width and length and depth of the joint.

Next time you are at the barn run your hand down your horse’s front leg stopping at the knee. Feel how flat the knee is on the front side. Now pick up his front leg and feel the way the knee flexes. You might be surprised at how wide the knee is. Remember that the 7 or 8 bones are organized in two rows, which explains the width and length and depth of the joint.

Gently feel the knee and see if you can sense the two rows of bones. You may not be able to identify all them but you will be able to find the most prominent carpal bone, the accessory carpal bone. In the horse this bone sticks out the back of the knee making it easy to find. The accessory carpal bone is concave on the medial (towards the body) side. Strong tendons run along the back of the knee and pass the accessory carpal bone.

Flex and extend your wrist then flex your horse’s knee by picking up the lower leg. Think about the motion in each joint and sense the similarity between your carpi.