Written by Bettina Drummond

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.9

Editor’s Note: The term “Iberian” refers to the peninsula where the modern countries of Spain and Portugal are located. Breeds of Iberian descent include the Andalusian, Lusitano, Peruvian Paso , Paso Fino, Mangalarga Marchador, Criollo, Azteca, Sorraia, Spanish Mustang and Barb.

Sometime ago, returning from a trip to Rome, I brought back a piece of marble from the Via Appia.

Having been there many times before, I once again marvelled at the Roman Empire, which lasted almost 1000 years and at its peak encompassed Egypt, Turkey, the Middle East, Greece, the countries up to the Danube River, France, and part of Germany, England, Spain, and their Celtic inhabitants, Portugal and the northern rim of Africa. An account of how this empire was built was written by Julius Caesar (102 BC to 44 BC) in his book De Bello Galico, which chronicled the Celtic wars. What is amazing is how such a vast empire could be governed from Rome without any of our modern communication and transportation technology. Part of the secret is in the Via Appia, an example of the Roman network of roads that spanned from one end of the empire to the other, including those built earlier by Persians, Babylonians and other civilizations.

Using these roads was a carrier organization a little bit like the American Pony Express, which operated day and night with layover stations every 25 miles, providing fresh horses and riders for the next section. Only the best riders and horses of the cavalry were promoted to these positions. But while we know a lot about the Roman foot soldier legions, their strategy, discipline, training and fighting exploits, less is said about the cavalry. Even so, it is the cavalry that was often the decisive factor when speed was essential or in outflanking their opponents.

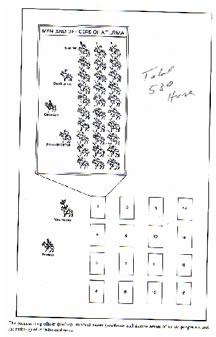

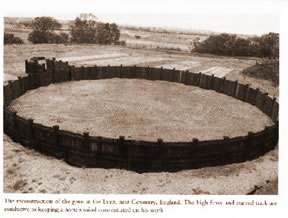

But through art and other historical sources, we can get a good picture of their highly trained and disciplined equestrian legions. It is from a text by the Roman Virgil that we first hear of the use of a training arena, ancestor to the western round pen.

These training techniques were invented by a Thessalian tribe who originated the first methodology of haute ecole. Their horses were of Persian blood from Nesae. Their conformation clearly showed an aptitude for chariot work in the low croup, powerful loin and high neck carriage. A high-crested neck, extremely flexible at the base, made these horses able to hold a higher point of contact, as well as translate a bending maneuver more easily, thus increasing the turning speed. The reactive pattern with their kind temperament made them suited to the many close maneuvers used by the Roman cavalry. In close combat their agility would give the rider more advantages, especially their unusual capacity to roll back on their haunches, giving their rider’s lance more leverage.

The Romans themselves were never good horsemen. They hired mercenaries from equestrian nations such as the Samaritans, Persians, Celts and others, ultimately giving them a Roman name and granting them citizenship. A well-known example is Flavius Arrianus, born 89 AD, who made a brilliant military career first as pro council in Cordoba, Spain, and later as governor and military legat of Capadoccia, or present-day Turkey. But he was not really Roman; he was a Greek of Greek descent and his non-Roman name was Xenophon. He left us with an outstanding equestrian work, Ars Tactica (The Art of Horsemanship). This work dealt not only with the strategy of warfare, but day-to-day training of horse and rider. When reading his treaties, one realizes immediately that only outstanding horses could lend themselves to these requirements and expectation and that the Mongolian ponies or lighter Middle Eastern and Egyptian horses could not make the grade.

So what horses did they use? Reading the works of the historian Marcus Aurelius (121 to 181 AD), also a later contemporary of Arrianus, we learn that the Roman cavalry horsrs were bred in southern Spain, in Andalusia, particularly between Sevilla and Jerrez. There is no doubt that the present-day Iberian horses are the direct descendants of the Roman breeding farms, which coincidentally were in exactly the region where Flavius Arrianus was stationed as pro counsel in the early days of his military career.

Horses from Lusitania were brought in to the Roman cavalry to fight in the Carthaginian armies. The native horsemen were shipped out to help the Spartans fight Athens. Their fastest bloodstock thrilled the Romans with their racing speed at the Circus Maximus. It was this breed and their training that made the Roman cavalry invincible and a dominant factor of the power of their empire. The breed showed the characteristics necessary for such endeavors in conquest through the powerful, broad back. It had to show an ample angle to favor long striding and a high, deep shoulder with a closed angle close to 80 degrees, slightly over the forearm. The flexibility of the dorsal region gave a resilient feeling to the rider and influenced an easier gain in muscle tone. This breadth of the lumbar region gave a lifting power with added muscular strength, increasing the endurance factor. This trait made this breed an asset to their traveling warriors.

Another especially developed trait was their elastic and elongated nostrils, able to bring greater respiratory capacity to the aid of cardiovascular endurance. The horses with greater space between the nostrils and the upper lip were prized, giving rise to the famous praise of Pliny the Elder, “Surely these are the sons of the wind.” Another prized characteristic was the width of the jaws—very muscular and able to mouth the bit gently, with well-set-back-lips. This facilitated the positioning in the chariot work, especially in the driving bit.

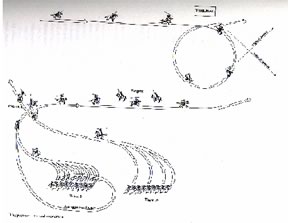

Thanks to their road system, their displacement from one area to another could be accomplished in a very fast time considering the local circumstances. All riding in the Roman cavalry had to be done with the left hand only, the same hand that had to hold the shield and a lance, leaving the rider free for fighting with the right hand. The concept of riding with only one hand was later picked up and expanded by the Duke of Newcastle in order to develop true lightness and self-carriage and avoid hand riding. The basic formation of the Roman cavalry was a shoulder-in position, presenting to the enemy a wall of shields protecting horse and riders, and from this collected position, a lightning fast start was possible. The lance warfare was taught to the Romans by the Ginete horsemen. These people are thought to be the forefathers of the Cretans and brought the tradition of the fighting bull immobilized by the horse, which in turn may have spawned the art of Cretan bull vaulting. These Ginetes lived in the upper section of the Marisma. They considered the horse to be a symbol of life, the bull that of death. The two became inextricably intertwined and a part of their religious worship. Later the Romans would put these two images on coins called denarii.

The Ginetes did not fight as a solid formation. They would fight as individuals circling around, waiting for the moment of weakness and then strike, relying on the speed of their mounts. Such guerrilla warfare tactics while mounted required of the horses a great aptitude for pirouettes and a solid ability to unify their topline to come instantly “on the hand.” The necessary obedience became a characteristic of the breed and their capacity to stay, in the words of the French masters, “a l’ecoute” made of them valued partners. Riders in the Roman cavalry were also trained in cross-country riding up and down hills and jumping with a modern crest release and forward seat over fences and walls, while approaching ditches and downhill jumps completely differently. In terrain like this, chariots were obviously useless and this fact was taken into account when selecting a battleground for their cavalry.

In addition, the Roman cavalry was provided with saddles increasing the rider’s ability and security in battle. To improve the effectiveness of their leg aids, they invented spurs. The necessity for a good seat was critical, since until then, riders fought bareback. With the advent of saddles, the rider could be less demanding of himself and more dependent on the horse’s training. Voice command was also a big training technique, particularly in charioteering, since the chariots had no brakes.

The uneven flagstones of marble of those superb Roman roads meant that hard feet and good bone were deliberately bred into these horses. The later Romans invented many shoes, notably a full leather pad which insulated from packing snow. They obviously took the weather in Great Britain into consideration.

Later, the descendants of these Roman cavalry horses were associated with outstanding equestrians— first by the knights of the Middle Ages and the Moors, then as the preferred horse of the L’Ecole de Versailles with LaBroue, Pluvinel, and Guèriniére.

The renowned “Guzman” breed, the “Valenzuelas,” were the Thoroughbred of the 16th century. Known for graceful and elongated gaits, they were very much in demand for traveling; the private sector thus profiteered off the Romans’ long history as conquerors through their breeding program. Many Andalusians were presented as royal gifts by Ferdinand, King of Aragon, to Henry the VIII. Charles II then imported many Andalusian mares. It was said that the Andalusian was the best in Europe and the first breed used for crossbreeding. During the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the most fought over prize was not its gold, but its Andalusian horses. The English racing blood owes its origins to this influx of Andalusian blood.

Some examples of the breed were brought to Lipizza in 1574 by the archduke of Austria and became the famous Lipizzaners of the Spanish Riding School. The Lusitanos and Andalusians remained the choice horse for classical dressage. In 1400, King Duarte of Portugal selected the first amongst them for this purpose and declared that they were the only horses with the courage and agility to provide a relatively safe ride in the Corridas. The Spanish and Portuguese horses were preferred by riders such as Nuno Oliveira and Alvaro Domeq.

Today, these direct descendants of the Roman cavalry horses exemplify the qualities which knowledgeable horsemen of the modern competitive arena seek. Although the warmblood has recently outstripped the Iberian horse in popularity for the sport of competition, none can rival the proud beauty the Iberian horse has inherited from the Roman cavalry ancestors.

Michel Henriquet in his dissertation on equestrian art gives the role of the Iberian horse its meaning by stating: “In order to birth equestrian art, it is necessary to instruct the horse, not merely train it.” He further states: “Equestrian art is differentiated from equestrian sport the same way ballet is differentiated from walking and physical exercise.”

Let us take a moment and reflect on how many centuries ago Romans took a practical need and brought through their horses a method of transport unparalleled to the world. Then let us leap forward and see Loui XV’s beautiful carousel of Iberian horses, dressed in gold, evolve into graceful and intricate ballet, as Versailles grandeur makes the perfect setting. Now, in the 21st century, these horses stand as the reminder that we can and must choose a purposeful way with these companions or a delicate entwining with a partner that is contributing its own style and acting its own role.

Bibliography:

Hyland, Ann. The Medieval Warhorse, From Byzantium to the Crusades, Grange Books 1994.

Hyland, Ann. Training the Roman Cavalry, From Arrianus’s Ars Tactica, Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 1993.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.9