Written by Terry Church

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.43

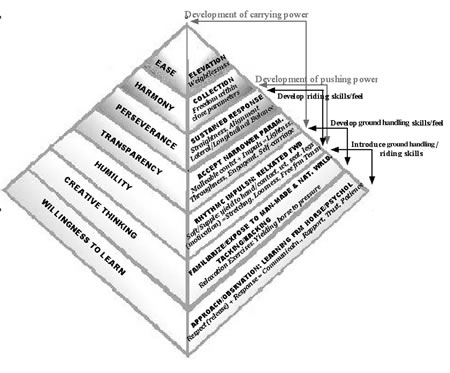

Previously, Part II in this series of articles presented some ideas pertaining to the second tier or stage (from the bottom up) of the training scale (Please refer Figure 1, page 10) and how those ideas might benefit horsemen and women of various riding styles. A few suppling exercises, already familiar to some, were suggested within the context of using those exercises to support our horse’s decision to “let down” from the inside, not merely to affect a mechanical, physical response. The continued development of our skill set, along with our efforts to improve timing, feel and our overall sensitivity to the horse and the world around us were mentioned, as well as some thoughts about what allows us to begin to think creatively and improve our ability to problem solve.

This article pertains to the third and fourth tiers of the pyramid. As previously noted, what is written on the page is, in real life, not limited to any tier, nor are the concepts presented absolute. My particular structure of the training scale is not meant to be an end-all, be-all of horse training, but is presented for the sake of communicating ideas in writing.

In Tier 3, Rhythmic Impulsion: Forward in Relaxation are written in caps on the right-hand face of the pyramid. This refers to the riding (or driving) horse who has gone through a familiarizing-to-the-world phase and has been started under saddle (or harness). In dressage-speak, which is often uncompromising in its definition of words, impulsion refers to the propulsive thrust generated from the hindquarters in trot and canter only. Because there is no moment of suspension in the walk, the word is not applied to that gait, in which case words like activity, liveliness and vigor are stressed. Regardless of the gait, however, I prefer to think of impulsion as a horse’s natural motivation to go forward, generated by a primary instinct for self-preservation—and play—and is what the species is built to do. Our horse’s emotional and physical willingness to move forward for us shows that we have learned to allow their natural motivation to thrive as we ask for increasingly complex and difficult tasks. A reticence to go forward could be described as a defense, a form of bracing, or a way of shutting down, indicating that some aspect of our rapport and partnership with them has been undermined.

A number of factors need to be in place in order for the horse to feel good about moving forward for us. One is that they respect and respond well to whatever aids we are using. In a recent issue of Eclectic Horseman, there was an article entitled “What Makes Horses Unresponsive?” by Martin Black (EH #40). In that article he spoke about how increasing pressure too gradually (from the leg, seat or will, perhaps) often creates insensitivity. When our horse doesn’t respond, it becomes essential to back ourselves up and then release whatever pressure we’re imposing when our horse has responded—as opposed to struggling or nagging for a response that is never offered readily. No one likes to be nagged, and we can relate to the reticence a horse might feel in such a circumstance. If, however, we’re willing to be students of our horses, we’ll be looking to apply a pressure and release in a way they understand, respect and respond to, not always in the way we assume we should, and not always in the way we were taught. What we were taught often applies to ideal or manufactured scenarios and doesn’t take into account the dynamic between horse and human in the present moment.

Our confidence in going forward with the horse is another important factor in sustaining their momentum. Horses with big strides can be intimidating. So can instructors who want us to ride more forward than we are comfortable doing. The resulting tension in our own bodies sends a mixed signal to the horse who then becomes resentful of our simultaneously jabbing legs. Or they might become discouraged and brace against us, making it feel impossible to “get through to them.” Discouragement is also created in a sport like dressage where there is widespread misunderstanding of the application of “contact.” I get to say this because I am a dressage rider who misunderstood. In my efforts to “put my horses on the bit,” I often inhibited their emotional, if not physical, willingness to go forward, my ambition clouding a need to slow myself down and figure out how to get to my goal in a way that allowed them to enjoy the work too. (More on contact will be mentioned later.)

Relaxation in our horses is another key factor in our ability to sustain their forward movement and have them happy to do so. A free flowing forward stride cannot happen without relaxation because the constriction in a tight or braced muscle does not give way to its maximum reach potential. By the same token, a constricted muscle often causes irregularity in rhythm, or in the evenness of the stride. Rhythm refers to the sequence of footfalls, or the time taken between each stride, as opposed to the tempo or speed of the gait itself. In other words, a lame horse would be said to have an uneven rhythm, regardless of how fast or slow it was moving. Rhythmic impulsion means that the forward is sustained evenly for the duration, as opposed to a going and stopping kind of motion, or a jerky stride when going from a straight line into a turn, for example. For an even rhythm to be born from the inside of our horse, impulsion—or our horse’s willingness to move forward for us—needs to already be thriving.

By the same token, rhythm is the ultimate test of true and thorough relaxation in movement. This is a hard thing to describe to those who have never felt it, but it has everything to do with moments that feel harmonious and effortless. A truly flowing rhythm indicates that our horse’s forward movement is free of all tension, bracing, irritation, reticence, hesitation or unresponsiveness, and is a joy to ride or experience from the ground. You know when you’ve felt it, because there’s nothing else like it. The danger is that, in a quest for such a feeling, many of us try to superimpose a preset tempo in order to find that steady, rhythmic stride before we have elicited our horse’s motivation to respond freely forward for us, unaware that too much confinement too soon is discouraging them. For us ambitious competitors who tend to focus on our own goals to the exclusion of our horse’s “inner” needs, their discouragement is not usually apparent until much later in the training when their tolerance level finally peaks and causes them to “shut down”—or exhibit more obvious behaviors of “disobedience,” as we would call it, thinking there is something wrong with them, or that they are “not suited for the training.”

Using Pressure to Affect

Suppleness and Relaxation

In the previous article, I spoke about the use of pressure to affect relaxation, not merely a mechanical response, and how a calm willingness can be transferred from the ground into the saddle. These are not new ideas, but when we are learning a specific exercise or skill, it is easy to remain attached to the horse’s physical response while ignoring the oftentimes more subtle signs that describe their emotional and psychological state. A mechanical response can feel soft and respectful, the same as one where enthusiasm or a genuine anticipation of pleasure motivates that response. Perhaps a bright expression will be all that clues us in to the difference. If we’re not paying attention, we won’t discern that expression and know when their response is rote and when they’re actually making a change from the inside. Learning to elicit relaxation while they are in movement can be a bridge to helping us reconnect with a truly positive response. Our horse’s ability to remain relaxed at any gait under saddle while staying confidently and willingly forward is a test of our own level of competence and feel. It requires us to adeptly coordinate our body parts and our aids. It also challenges us to broaden our sensitivity, so that we are ever noticing what is going on underneath the surface.

While riding, we have the opportunity to use our intention or will, our reins (contact), weight, seat and legs as a means of applying pressures that not only affect simple responses (like moving in a particular direction), but that also affect a yielding in the horse’s body, allowing them to release bracing, tension, tightness, and resistance. There is not room here to describe the innumerable ways we might achieve this and how we need to coordinate ourselves in the process, but here are a few ideas that might be helpful to consider:

Lateral Suppling

Any lateral or sideways movement can be used to help our horses release bracing laterally, or along the sides of their bodies. Flexing a rein (and then releasing that pressure when our horse has yielded to it), bending in circles, serpentines and figure eights, riding turns on the forehand (crossing the hind legs), and leg yields (side passes) can all be used in this way. In dressage, these types of simple exercises were designed specifically for that purpose, a fact that is often forgotten by the ambitious competitor who rides movements to win ribbons. While movements and exercises can be fun to execute in and of themselves, there is again the danger of riding them mechanically or by rote, causing us to forget their greater benefits, one of which is to help the horse become supple. Suppleness indicates a release of tension, allowing for relaxation and freedom of movement in whatever “job” we are asking our horses to perform. Freedom of movement means they have found a place “between our reins and our legs” where there is no pressure.

Ray Hunt often talks about how he doesn’t want his horses to weigh anything. This idea makes perfect sense when we think about how miserable it feels to lead a horse with a constant pull on the lead rope or the reins. Yet somehow we manage to tolerate all kinds of weight in our reins and against our legs while riding, convincing ourselves it’s just the way our horses feel. But weightlessness (tier 7 in the pyramid) is an outcome of instantaneous responsiveness and is a pleasure to experience. We might also consider how essential it is for our horses. Allowing them to find relief or freedom from the pressures we impose upon them is allowing them the freedom to be who they are—while being with us. For example, when we ask our horses to perform an exercise or a job, there is a moment when they try for us. That’s one moment where we might ease off the pressure, becoming weightless to them. Then there are the moments when they “let go” and yield a part of themselves over to us, becoming softer and more at ease. This usually happens somewhere in the “middle” of an exercise, movement, or job we thought was so important to “complete.” But if we are being attentive to the horse’s well being, we’ll release the pressure of our urging—or a rein or leg or seat bone—at whatever moment they begin to let go. In the beginning, feeling for the quality of their response far outweighs executing a perfect movement or exercise. As our horse becomes adept and confident in how to respond to us, our releases can be shorter lived and less obvious so that in the next nanosecond, we can redirect and continue, and then complete the task at hand.

This was always the rub for me. For many years, I never wanted to look “messy” or inept. I wanted to complete whatever it was I set out to do to prove I knew how to do it. I didn’t realize I was merely living in the world of mechanical response, and that my definition and experience of agility was only skin deep. During this time, I remember Tom Dorrance encouraging people to think about how they put their shirt on every morning. Did they pick it up with the right hand or the left? Which part of their body did they cover first? If it was their arms, which one was first? Which leg did they first step through their pant legs with? When they turned to another person, which direction did they turn their body or head? And then, after they noticed, could they switch it up? Could they brush their teeth with their non-dominant hand, or even just reach for a cup or dinner plate? He never said this to me directly, so I never had to feel too embarrassed to admit that I’d assumed my horses should be able to work from both sides equally without holding myself to the same standard.

Tom had that kind of genius for offering shots of humility without making people feel bad about themselves. His approach helped me be more honest while learning to assess a situation without judgment. This, I realized, was more important, or helpful to me and my horses, than being “right” and looking the part. I learned to admit that, if I was trying to dig deeper, what worked for me today could not be turned into a recipe for tomorrow, and that all my assumptions about what should work only got in the way of learning about what was the most appropriate way for me to present myself to the horse in the present moment. If I didn’t maintain this transparency, at least inside my own skin, I could not continue to learn what I wanted to know the most, which was how to relate to my horse, to other people, and to the world around me.

Longitudinal Suppling

In addition to using lateral movements to help our horses relax under saddle, we can use our aids to affect relaxation in our horses longitudinally, or over the top line. One way to achieve this is to use “contact.” Many people think of contact as the feel (or pressure) in the reins that determines their connection to the horse’s mouth (if riding with a bit) or to the nose (if riding without a bit). That idea is a beginning. Ultimately, establishing a truly good feel in the reins is the outcome or final step of a number of components coordinated together. A fuller sense of contact can be achieved when the activity or thrust from the horse’s hind end sends the horse forward into the pressure of the reins—a pressure that is once again used to ask the horse to soften by yielding to that pressure. If adequate forward is sustained, the horse will yield not only with the head and jaw, but through the entire length of his body (throughness, tier 4).

To quickly demonstrate this idea to yourself, take a dressage whip and place each end in the palm of your hands (See Figure 2). Hold your arms up vertically in front of your face with the whip still in each palm, spanning the distance between your hands. Pretend that the handled end of the whip is the horse’s hind quarters, and the tasseled or lighter end is the head. If you push the “hind quarters” toward the “head” with the right torque and pressure, the whip bends upward. The hand that holds the “hindquarters” represents your forward driving aids and how the horse moves forward into your hand, representing the pressure of the rein. As the whip bends upward, it represents the action of the horse’s back or entire top line as he yields to the bit (or nose piece) while moving forward. The exercise can help us conceptualize how the yielding action goes through the length of the horse’s body, not just the mouth, nose or jaw. While riding, we can literally feel our horse’s back come “up” underneath our seat. The feeling resembles the beginning of a buck, only in this case there is a sense of relaxation along with the forward flow, making it a pleasure to ride.

Most horses initially back away from pressure applied with the hand. Yielding to the rein while moving forward takes much more mental and physical effort for them to figure out, and requires much more skill from the rider (or driver) to coordinate. For the horse initially, it’s like being asked to stop and go at the same time, causing confusion and irritation unless the rider learns to keep sufficient forward momentum and also learns how and when to release the pressure of the rein. If the rider does not sustain consistent forward momentum, then the horse will yield with the head and jaw only. The “scrunched” result in the neck often ends up feeling light in the hand, but does not include malleability and freedom of movement throughout the whole length of the horse’s body, therefore compromising his sense of comfort and well-being, emotionally as well as physically.

In the beginning, creating a “loop” in the reins while giving forward with our entire forearm is often what it takes to convince the horse that there is a place of freedom from the pressure if he yields to the rein a little (See Figure 4). Here is where many of us get yelled at for “dropping our horse” and “riding too fast.” But again, if we are to ask horses to work with us and be happy about it, then we need to find ways that help them make sense of our actions, not necessarily ways that start out fitting an image of how we think we’re supposed to look ultimately. Over time, as our horse learns where that “place of freedom” is between our legs and our hands, our releases can become progressively imperceptible.

When riding on a shorter rein, we narrow the parameters within which our horses will be asked to work. (See Figure 5) Riding them “round,” or with the whole back and top line “up,” allows them to release braces longitudinally and continue to move freely as we work toward collection—or their ability to carry their weight progressively toward the hind quarters—which enables us to ride more difficult and exacting maneuvers, whether in dressage, cow working, jumping, or simply walking down a hill with ease. Their ability to work within the parameters we set with a shorter rein and be comfortable with that degree of confinement is a process that requires patience. In the long run, however, being considerate of the horse takes much less time than having to undo all the tension and resistance that we otherwise create.

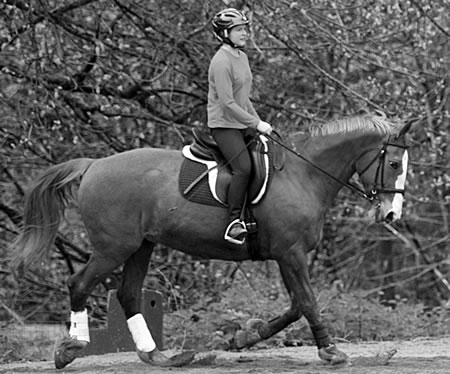

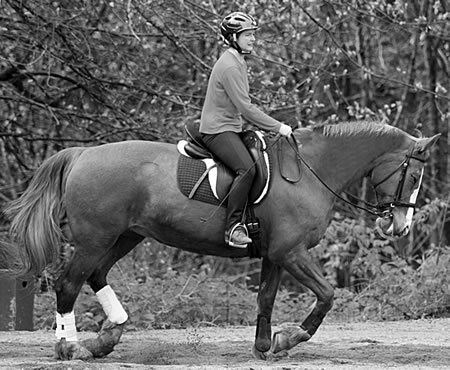

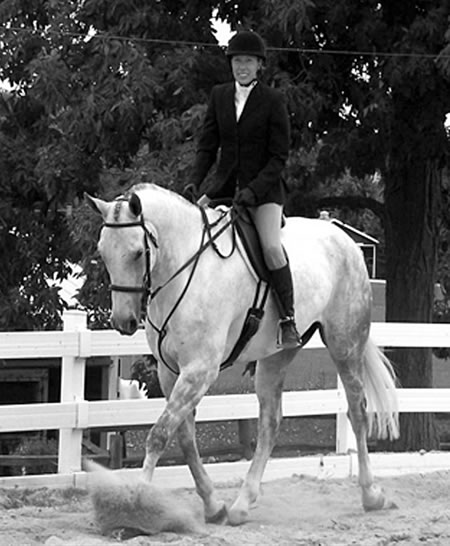

In figures 6, 7 and 8, note the light rein contact and the “round” top line, but also the bright expression as softness runs through the entire length of the same horse being asked to perform several different jobs. Horses will remain willing to do anything for us if we allow them to find a place of freedom within whatever parameters we ask them to work. Any residual poundage in the reins indicates that there is still a brace somewhere in their body, which is ultimately restricting their stride and forward movement. It also means that our horse is not in self-carriage (tier 4), but is relying on us for balance. Self-carriage can be present regardless of the horse’s head carriage, whether at a full stretch, while moving in collection, or anywhere in between. Self-carriage can also be achieved with a nose piece. Whether or not a bit is required to sustain the quality of throughness in upper level dressage work or in more complex maneuvering for other disciplines is a subject that might be better addressed in another discussion.

As mentioned in the previous article, allowing our horses to stretch periodically affords them a time of adjustment, a moment to let down, and reminds us not to hurry the process. For horses doing collected or advanced work, stretching relieves the weight from the haunches, allowing the blood to flow back into muscles that have been working hard (See Figure 9). For green horses, the improved reach of the hind feet (leading to engagement, tier 4), prepares the hind quarters for collection later on. In spite of the worry that some have about “throwing the horse onto the forehand,” stretching reorients any horse to releasing tension while in movement, or to be “forward in relaxation.” Only a relaxed muscle can be adequately strengthened and prepared for the work to come.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.43