Written by Eclectic Horseman

A collection of memories from Eclectic Readers about the late Tom Dorrance.

Connie Brown:

I never knew Tom Dorrance but all of my “teachers” are horses and trainers from his lineage. He made a great contribution to the good for both horses and horsemen and horsewomen today. Every day I delight in the relationship I have with our horses and my understanding of them, which has been passed on to me by Tom’s example and students like Buck and Marty and Amy and Steve LeSatz. Tom and Bill Dorrance have shown us all how to have a satisfying life by sharing of what they loved and could do best.

John Sanford:

I would like to thank Tom for teaching those who have taught me. If there’s a place beyond here with horses, I sure Tom and Bill are riding together again.

Jan Leitschuh:

Tom changed my life. It’s that simple. I didn’t know it at the time, but Tom rearranged my way of looking at things. It was about more than horses. His ways were about life, the journey. In fact, this altered perspective was part of what gave me the heart for my current project, a sabbatical to walk the entire Appalachian Trail. I am 1,386.5 miles into the 2,000 journey. “Adjust to fit the situation,” indeed! I am grateful for the time I was able to spend with him one-on-one. What a gift!

Julie Arkison:

Dear Tom,

Maybe you already know how much your observations with horses have helped people be able to interact in more meaningful ways. The story seems to be the same: people see others working with horses using the sight you have given many and say, wow, that can help me with my spouse, child, friend, boss etc. etc. Their world tilts just a little as they watch someone working with a horse, in the way you have given us, and they see from a different angle. They know their actions will be affected in the future and a kind of excitement shows in their eyes.

On a beautiful Fall day this week, my sister and I went for a walk with her 2 – yr. old son. Jennifer is the first to raise a child in our family and I admire her. My work with horses seems to pale in significance to the importance of raising a baby human. As she struggles with how to relate to this growing and changing being, I tell her stories from my horse world- about pressure, release of pressure, watching for the slightest try and the smallest change, about body language and tone of voice, spatial and spiritual awareness.

She often laughs in that happy way people do when they are given a third option, when the first two don’t exactly feel like they fit. Then she gets a curious, soft look as she reflects on this new approach. The mind stops for a minute there, suspended above the past, watching for a new awareness that emerges from reflecting on what WAS with NEW eyes. The past takes on a different meaning because the future feels alive with possibilities for something different. . .

My sister, Jennifer, was struggling because Hayden, her son, was running and laughing, waiting for her to play his favorite game of chase. Problem was he was running into the street. Cars don’t have much meaning for him yet. He clouded up, ready to cry because she had firmed up- problem was it was AFTER he’d started running. So I decided to make any driveway or street corner into a waiting game. Any time the pavement changed from grass to concrete I got real still and quiet and whispered “Wait Hayden, do you see any cars?” I looked both ways and then said “O.K. no cars, lets go.” He started to get into the idea and we made it into a game. I got into watching his body and face for little tries and got to using my body in ways I thought he could watch for. Pretty soon I had subtly built on an invisible leash through driving and drawing his attention. And we all breathed a sigh of relief for the rest of the walk.

My God what a big job it is to raise a baby human!!! Thank you Tom for giving me new eyes from which to view this precious job. I’ve pretty much decided I may not have the courage to go there myself but maybe I can help my sister out and I feel good about that.

Tom, I just wanted to say that I hope you know that you will leave the world a better place for your having been it. And thank you.

Love, Julie

Joe McGowan:

Like all of us who received your e-mail I was deeply saddened by the loss of Tom Dorrance. I never had the honor of meeting him but he has greatly influenced my life as he has the lives of so many others.

Maybe Curt Pate said it best “I want my horses to look like Ray Hunt’s and to have as many friends as Tom Dorrance”. He will be missed but never forgotten. The gift he gave to all of us in this community will be cherished and nurtured for a long time to come.

Bettina Drummond:

For the school of N. Oliveira, I send to all of you who knew this man of feeling and compassion for both people and horses sympathy and condolences .Also the sincere hope that those whose lives he touched and whose talent he brought to life continue to honor both the horseman and the teacher .

Diane Longanecker:

I’ll always admire Tom’s quiet, respectful way of allowing and encouraging the horses and people he met to be themselves–thus honoring each individual’s essence.

Paul Reed, MD:

I wish I could say that I had the pleasure to meet Tom Dorrance in person; heard directly from him his stories, experienced his love of horses face-to-face, or even had the pleasure of seeing him work with horses. But, regretably I haven’t. I have, however, been introduced in to the culture of horses and horsemanship that he defined and set the standard for. His name has been held up above all others in reflection on what it means to be an intuitive, intimate friend to horses. I am a new-comer to this wonderful life with horses, only as recently as the past few years after having met my wife.

Suzanne often speaks of her experience in a clinic with Ray Hunt and relates how it transformed her relationship with horses. She and I have a terrific 5-year-old gelding who is calm, responsive and understanding. What little I know of horses I have learned from him and Suzanne through the philosophy that Tom Dorrance esposed. I am not naive and I know that there are many diverse ways that men have engaged horses over the centuries. I have seen some less than reasonable approaches while living in Spain. It was my fortune to be brought in to the culture from Suzanne’s perspective – that of Tom Dorrance. I appreciate his approach, his philosophy, for many reasons – mostly, because he and those who have followed in his insight relate to horses as intellectual, emotional beings. To appreciate the intimate trust a horse is capable of and willing to render to man is the strength of this philosophy in my opinion.

As a pediatrician, on a daily basis I see the best and worst there is in parenting. I have come to understand that the greatest first step to being a wonderful parent is to realize the trust that a child is anxious to share. That they yearn to have in you as a parent. I have seen the same desire in every horse’s eyes that I have come face-to-face with. I hope to further grow as a horseman with the understanding and intuitiveness that Tom Dorrance has shared with all of us. Though he has passed away, I have no doubt that his legacy will continue forever in the relationship men have with their horses.

Millie Hunt Porter:

When I returned home to Idaho, after being in Carmel Valley, California, on June 29 for the memorial gathering to honor Tom Dorrance, I got the message of plans to devote this edition of Eclectic Horseman to Tom’s remembrance. Tom’s memorial in California was held only a few miles from where he had spent his last years. Folks who had traveled from out of state, and even out of country, attended. From the folks who spoke, to those who nodded in agreement, it was easy to see this fellow from eastern Oregon had touched many lives.

For the first 50 years of his life, Tom had stayed pretty close to his home range, taking care of his parents and the family ranching business, and being a part of the local community. I understand, after his siblings left home, Tom had challenged himself to develop the skills to do more and more of the ranch work without any help. Being a deep thinker and problem solver, this time alone gave Tom more understanding of ways to “get things to work for the horse and himself” as he used to explain.

I first saw Tom 43 years ago, after the property in Oregon had sold and Tom was spending more time in Nevada and California. I feel I can say I was amazed at what he had to offer a horse. To me what he could see and understand about the horse was unreal; watching it seemed mystical and magical. Now that I have said amazed, unreal, mystical and magical I need to be very clear to state I always felt from Tom’s perspective his connection with the horse was very natural and real, with absolutely nothing mystical and magical about it.

Before seeing Tom’s work around horses, the most accepted method of getting the job done seemed to depend on training the animal to understand what the human wanted. Tom’s approach seemed to be the reverse. The emphasis was on humans to understand what the horse needed. This was the paradigm shift from “working on the horse—to working on oneself.” Not every rider exposed to this thinking made the shift, but for the ones who accepted the change, a door was opened to an exciting journey of discovery.

Fortunately, Tom stayed accessible by the telephone, personal visits and group lesson sessions. Tom continued to help individuals and groups to understand and apply his ideas.

In the introduction of Tom’s book, True Unity, published in 1987, his brother, Bill Dorrance, says of Tom “…he never liked to be in trouble himself or have trouble with the horses or stock he was handling. That’s probably why he spent as much time as he did trying to figure out horses.”

One section of True Unity is feedback from some of the students Tom helped. The section is titled “Tom’s Students Visit about Tom.” Through the years Tom called the sessions of helping folks “visits.” Referring to the time spent learning as “visits” seemed to help keep a relaxed attitude.

In these “visits” Tom did everything he could to share his knowledge and feelings about the horse—leaving me with no doubt Tom changed the world of horses. One of the strongest sentences from his book he often said was… “The rider needs to recognize the horse’s need for self-preservation in mind, body and spirit.”

Joyce Mattos:

I’ve known Tom and Margaret Dorrance for nearly 20 years. Over those years they’ve become the truest friends I’ve had. To limit Tom to the words I could use to describe him has always seemed an injustice: he was so much more than any aspect I can tell about. Tom was unique; not only among horsemen but in any population. He was a thinker, a man who possessed the keenest powers of observation and memory. What he observed and remembered from one experience, he could use to help him in another situation. These were abilities he tried to help others develop in working with their horses because he said this was the basis of his horsemanship: what he knew about horses came from the horse. He had closely observed them as they lived and interacted in nature and with people and applied the information he gained from these observations to help the horse accept the person.

What distinguishes Tom from anyone else I’ve known is the degree of integrity with which he lived life. What Tom was with horses is what he was period. The same true heart that reached out with honesty and respect for the horse guided him in all his relationships and dealings with people. Never once did he put another person down because they didn’t see a situation (with a horse or otherwise) from the same perspective he did. He was yet willing, if the person was, to try to help them understand his perspective and if it helped them, to add his way to theirs. He didn’t need to remake others in his image, but he was always willing to share his knowledge if a person was ready to listen. And he was always learning.

He often said that every horse could teach us something new. He saw them and people as individuals, each with their own story to share. People were often very serious when they were around Tom, I suppose because they were intent on “learning from the master.” Never once did he take himself too seriously. Tom liked to lighten the moment with his quiet sense of humor that sometimes was lost on all that seriousness. He could recite a poem that just fit the moment, like the time I was telling him about getting my arms caught behind me as I tried to take off a windbreaker while sitting on a green horse on a breezy day. Just as I had both arms behind me, the breeze flapped the windbreaker and we were off and running. Fortunately, I was able to extricate myself and it all turned out all right. Just as I finished retelling the events to Tom, he broke into a recitation of a favorite poem, “Slicker Break a Bronco,” to remind me that there are some things to prepare a horse for before you need them!

More than once, after a long and serious discussion of how to work with a colt that was having trouble with me, when Tom had explained some in-depth understanding of what would help the colt and me find our way out of trouble, Tom would finish by saying, “Now try this, and if it doesn’t work, call me back for some more ideas that don’t work!”

One picture of Tom that always comes to mind happened with the first colt I ever started with Tom. Tom had helped me with some other horses I had, so he knew I was pretty green.

I then bought an unstarted colt from a ranch where Tom and Margaret were working starting colts. I guess Tom knew when I bought the colt that part of the deal would have to mean some work for him trying to keep us out of trouble. He came to my place and we worked several times to prepare the colt for the first ride. When Tom couldn’t delay the inevitable any longer, he helped me get on. He managed to keep things below the panic level for a few steps, but later he said he knew the colt was thinking he should do something, so before he figured out what, Tom had me step off. He then proceeded to lay the colt down in his very gradual way that didn’t scare the colt, but instead increased the colt’s confidence in Tom as he gave himself over to what Tom wanted him to do. After the colt was lying down, Tom went around and flexed his legs until it was clear the colt was completely relaxed. Then Tom stood on the colt’s hip, took off his hat and bowed. With great seriousness and only a twinkle in his eye, he told me, “If this was done right, it is guaranteed that the horse will never buck. The problem is you won’t know if it was done right until you get on and ride.”

Bryan Neubert:

Tom Dorrance is probably the smartest person I have ever been around. I’m no judge to say who is a genius and who isn’t, but if I ever were around someone who was a genius, Tom was it. I think sometimes that the only reason he was so good with horses and cattle was that he was born into the middle of it. If he would have been born into a family that was around airplanes, he would have been a fantastic aviator.

The fall I spent with him he didn’t ever lose patience with me. Some of the things he was trying to get me to understand were not easy. I just kept thinking how did he ever get on to this without someone there holding his hand. I could barely grasp it, and he was there helping me every inch of the way. How did he discover things differently than everyone else?

Tom was a man of high moral character; he had a lot of self-discipline, but he also had a wonderful sense of humor. He had an almost childlike way of playing, to where he was almost silly sometimes. Anyway, this is a little story about what kind of character Tom had:

We were in Dillon, Montana, where Tom was putting on a clinic. We were staying with the host of a clinic at his ranch. He had a house full of guests, and his wife was trying to take care of the family in addition to the added company, and she was really getting frazzled.

At dinner Tom was the center of attraction; he was the reason that all the guests were there. And when supper was finished, everyone was ready to sit back and pick Tom’s brain about horses. But as soon as people finished eating, Tom got up, went to the sink and started washing dishes. I went in to help; he washed and I dried.

We did all the dishes from the dinner plates to the pots and pans. See, he did what anyone of us should do. But there was the whole table waiting to talk to him, and he had read that the host’s wife was frazzled and so he went in and washed the dishes. That was just his nature.

Sheila Varian:

(Excerpt from a forthcoming book)

I won the Open Reined Cow Horse Championship at the Cow Palace in 1961 and was back teaching school every day, riding horses in the afternoon. A small older truck with a tiny camper bed chugged up the hill to the house. Amid my dog barking, I walked out to see who it was. A short, stocky man with a shy smile opened the truck door, climbed out and introduced himself as Tom Dorrance. I had not heard of him. He asked if he could look in the barn and I, glad to have a little interruption, said “Sure.” He walked around the six stalls and made appreciative comments about the barn, the horses, where I lived and then mentioned that he was traveling, learning about horses. Tom said he had learned some interesting things about horses… My ears were perked immediately… “Really?” I asked. “I saw you show your bay mare Ronteza at the Salinas Rodeo and she did a good job”, said Tom. “I thought you might like to visit for a while… how about looking at that horse over there.”

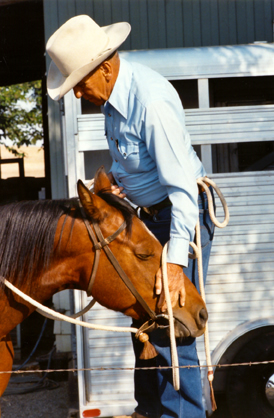

With that little introduction, my philosophy about working with horses was given direction. I am a horse lover, so hurting a horse to teach him never felt right. Tom has become, with his quiet nature, in my mind, the greatest influence on understanding the horse’s mind of any one person in the history of the horse. In the quiet days we spent together at my house, he opened his knowledge of the mind of this horse I loved so… That the horse is a herd animal and all of his reactions are genetically engineered to reacting as a herd animal. That given a choice, the horse will always seek out the comfortable way… That we need to encourage the horse to trust us as we impart information, but we must be a partner in the decision making. Walking into a stall with a grey filly, Tom’s strong, gentle hands massaged the top of her neck just behind her ears. At first, she tightened her neck muscles and raised her head. Tom continued massaging with just enough pressure for her to make a choice—resist the strong massaging hands and lift her head, or relax and drop her head.

Momentarily, she resisted, tensing her neck, and Tom continued massaging, not pushing her head down, simply applying pressure between his fingers… “adding life to my hands,” he said. Seeking a little more comfort than she was getting, the filly lowered her head and Tom’s squeezing fingers softened and then relaxed. A moment later, he applied his fingers to her neck again, and she immediately softened and lowered her neck. Tom started talking about “trust and partnerships,” that we show the horse the door, then open the door. If we open the door and we haven’t created mental barriers of fear, the horse will look for the open door every time. If the horse’s mind is cluttered with doubt, it will take longer for it to find the door, but we can regain the trust by simply setting up situations in which the horse will be successful and gain trust by the comfort of going through the door. Simplistic as that sounds, it was quite mind-boggling to put into action. My feet and hands and eyes had to learn to see and feel, then be able to move when the horse was in the process of responding as I wanted him to. It took more time and effort than a person would like to admit to becoming proficient in guiding the horse to make the choices we had in mind for him.

Tom left me with my mind going round and round… I felt as though my eyes were crossed and coming out both ears. I couldn’t leave it alone. Everything was a test—I’ll get this horse to be comfortable to lead by his ear—well, if I can make him feel comfortable to lead by his ear, how about his nose… would he mind being led by a foot? Can I get him to put his head up or down by the weight of my hand on his poll? Can I get his body so relaxed that whichever part of his body I push on, it will softly flow away from the pressure, as though pushing a ball and having it roll away at the same intensity that it was pushed? Well, you can see what this did to my simple mind. As Tom drove away, he knew, of course, that this learning process would take about a year and so I didn’t see him for a year.

I began to look at everything I wanted the horse to do in very small steps and increments… open this door, let the horse see and go through, open the next door and so on.

Small steps, open doors and by spending the time and making the effort, you will become as competent as you desire to become. Tom Dorrance takes this to the master’s level and has been willing to impart his knowledge to thousands of people. I asked Tom if I could pay him the next year after his unplanned visit, but he wouldn’t hear of it. Said he was learning as much as I was. Typical Tom. It spoke volumes about a man that loves horses and only wants for them, not for himself. Tom’s brother, Bill, has been an enormous influence as well, although I didn’t know Bill very well. We have many people that carry on Tom’s work—Ray Hunt was the first. Good with a rope, Ray made the cowboy way look easy, and all horses happy. Buck Brannaman is an excellent teacher with very responsive horses. Pat Parelli, with his seven games. All add their own approach. And then there are people like myself, who are fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time, share whenever there is an opportunity. Our methods all stem from and follow Tom Dorrance, who spent his lifetime teaching understanding for the mind of the horse, which has made life ever so much more interesting for we horse people, and unbelievably more comfortable for the horse.

Deb Bennett, Ph.D.:

There are some bits of cowboy poetry written about Tom Dorrance that have stuck in my mind for years. One had to do with a ranch family that hired Tom to take care of their rough string, but having Tom around, they soon found out they never had a rough string. When I got lucky enough to meet Tom and spend some time with him, he catalyzed the long process of getting the “rough string” out of me. I think Tom did this for a lot of people. He taught us some very deep truths in a way that we could understand. He was a master of “putting the worm in the woodwork,” and then, with greater faith in the worm than I would have been able to muster, he left you alone to let the seeds of change sprout and maybe even bear fruit. He wasn’t teaching us aids and cues, but how to look within. Tom said again and again, “please remember—you have to ride the whole horse.”

Tom operated by the oldest scientific dictum in the world—”observe, remember, and compare.” I have known many great scientists, but I never met a more lively or perceptive intelligence than Tom’s. He was the most creative man I ever knew: every day was a new day, every horse was a new adventure, every situation demanded, and was given, a unique response. No horse—and no student—was ever treated just the same as any other. Tom started no “movements,” indulged in no slogans, promoted no set method, trapped no one in “levels.” Instead, he opened doors and invited us to a full and responsible freedom.

My guess is that Tom preferred the company of horses to that of people, but he was always delighted to meet any person who showed a willingness or an aptitude for seeing things as he did—from the horse’s point of view. Tom taught that you ought to get it to where the horse would rather be with you than anywhere else. But I felt the same about Tom himself, and I miss him.

Someone at a clinic once introduced Tom as “the master of from zero to one.” That title is, I think, both apt and important. So many times, I saw Tom ask people to cut the pressure or demand they put on the horse in half—then in half again. He encouraged us to take this to the limit—how little might it really take to obtain a response? What many of us found—to our shock and amazement—was that the horse began not only to “obey” but to “come from the other side” with generosity, evident intelligence, kindness, and joy. The horse, it turns out, is chock-full of desire to help the human. Tom taught us all where to find the path to this good place—the same good place that every horse wants to be in at every moment, and the same good place that Tom lived in and lived toward all his life. Tom showed us that the most important thing we can do is to consider our every action’s meaning to the horse.

Tom certainly came along at the right time in my life and in the lives of many others. It has been a special boon and blessing to have had him among us. The corral gate has swung open, and our teacher has ridden on home. As the cowboy poet sang, “his timing is perfect, his dues have been paid.”

Martin Black:

Tom Dorrance is the only person I know of with the ability to put his emotions and motives aside and focus on the horse’s emotions and motives. Tom would say, “Before the inside of the horse can be right, the inside of the person needs to be right.”

Tom had a gift from God. Money couldn’t buy it. Tom couldn’t sell it. People went to great lengths to get it, Tom couldn’t give it away. In this mechanized, hi-tech age, it’s hard for people to grasp something as old as a breath, two souls striving for an inner peace.

It would be frustrating for me not being able to do something with a horse, but if I would just think of some of the things Tom repeated over and over, it helped me. Like “fix it up and wait.” I didn’t mind fixing it up until the sweat was pouring off me and I was out of air, but that waiting was real hard for me.

I regret being so thick-headed and taking so much of Tom’s time with so little to show for, but I am truly grateful that he prepared me to find the doors and open them up to find what he wanted me to find.

Tom was truly a peacemaker. He was uncomfortable knowing a person or animal was grieving. He would try to help out where he could, and accept what he couldn’t change. He didn’t try to rewrite the laws of nature; he wasn’t out to improve one life at the expense of another.

Terry Church:

Yesterday, at Tom’s memorial gathering in Carmel Valley, I sat and listened to many stories that others had to share. I was with several of my working students who had never had an opportunity to meet him, but whose lives and careers have been so profoundly influenced by him. I never got up to speak – there was too much to say. Thank you for providing a space for me to write some of my thoughts down on “paper”—a venue I much appreciate being able to express myself through. Here are my thoughts:

In giving clinics around the country I have had the opportunity to meet many horsemen and -women who are on one path or another, searching. On a flight home one time I heard Tom’s voice in my mind: “Every person is a gift,” he said, and I realized that he never showed any doubt about someone’s ability to begin from wherever they were and move towards some better place. For me it began with an attempt to better my relationship with my horse—horses were usually, but not always, the means by which he helped the willing make the journey.

“How do I do it?” I asked him, watching myself mechanically cue another mare into a compulsory movement with her ears pinned —then later rush to some appointment, cut someone off on the freeway, barely stand long enough for a person to finish their sentence before I was off to the next thing—I can’t remember what it was now, but it seemed real important at the time.

He never answered me directly, regarding me instead in the same kind manner in which he wanted me to treat my horses, myself, another person, all living things. It seemed like most people thought he didn’t put it into words because he couldn’t. “He doesn’t know how to explain things,” they’d remark, thinking they already had the answer and could say it better.

“I never liked calling myself a teacher anymore than I like calling myself a trainer,” was Tom’s reply. “And if I say something too specific, then the person tends to focus on that one thing, instead of learning to see the big picture.”

The big picture. The third factor. The spirit that can’t be contained in a mold, can’t be defined in a list of instructions. With Tom you had to be willing to be there inside yourself, beyond the confines of assumptions or preconceived ideas about what you were supposed to do, say, think – or how things were supposed to end up. Most of the time for me that meant feeling like an idiot – the “type-A” work-a-holic perfectionistic competitive Dressage Queen didn’t know all she thought she knew after all.

But then there was the feeling that came when I stopped trying to prove myself, when I stopped trying to preserve what had once made me feel so important – and just be with my horse. Observing. Learning without judgment. And it was the “without judgment” part that took me the longest. How can I ever describe what it was like to spend part of my journey with someone who knew about that, who treated me with utmost respect in spite of all the ways I’d been lying to myself – as if I mattered anyway?

“And now what will we do without Tom in the world?” I hear a lot of people ask the thing that’s on everyone’s mind. But as Tom would say, “Learning has to come from the inside of a person, same as it does for the horse.” It was that self-reliance that he waited for in each of us, regardless of the hours, days or years that it took to finally happen.

It takes courage to trust oneself, to risk trying something different because it was our horse that showed us we were missing again, to ignore the criticisms of other trainers in high places who knew the way you were supposed to have done it because it was the way they were taught and so it must be right. Yet each of us has the power, the ability to take the journey from our place of ignorance toward being a little more aware, a little more respectful of the spirit in all things. In this way each of us continues Tom’s legacy, whether or not we were one of the ones fortunate enough to have worked with him. Our daily progress, no matter how small, is our gift—and our proof that we have not really lost the one who may have helped us realize it to begin with.

Marty Marten:

I have been very fortunate to have spent time with Tom Dorrance since first meeting him in 1989. Everyone knows that Tom knows how incredibly good his insight and understanding of what is going on with any particular horse was. I would, however, like to reflect on some things that hopefully demonstrate Tom’s other side; that is his interaction with people.

I hosted two clinics for Tom at my place in Lafayette, Colo., one in 1993 and the other in 1996. Tom is very well known for his observation skills with horses and people. While here for his clinic in ’93, I arranged for Tom to visit his longtime friend, Terry Swanson, DVM, at Littleton Large Animal Clinic. As Terry was giving us a tour, he took us into one fairly large room where three people stood at a table writing on clipboards. Pretty soon Tom commented, “Do you have to be left-handed to work in this room?” I am quite certain by the reaction, Tom was the only one who observed that fact.

After the second clinic in ’96, I took Tom and his wife Margaret to the airport to fly back to California. Tom was getting around pretty good with two canes, but I arranged for a courtesy cart to meet us at the front door and take us to the Dorrance’s boarding gate. It was otherwise a long walk for him.

As we sat waiting for the cart to arrive, I acknowledged to Tom how good he was getting around with his canes. However, I said, when the cart arrived, that he might want to appear sufficiently needing of it when he mounted up. Tom played that part well. As we sped off toward their boarding gate, Tom leaned over to me and said, “How was that, do you think that convinced the driver?” It was all I could do to keep from laughing out loud as I said yes.

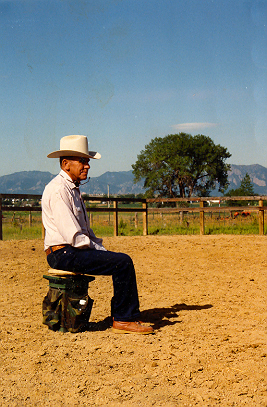

In February of 1999, I visited Tom and Margaret’s home in Salinas, CA. They were giving me a tour of their house, including showing me the numerous photos framed and hanging on the wall. Tom pointed out a photo of him horseback, back to the camera, throwing a loop, sailing through the air, ready to settle on a horse in the round corral. Margaret quickly pointed out that Tom had told her when to snap the photo.

It was a perfect photo of a perfect open loop in the air just before catching the horse. That photo and the visit has since been permanently etched in my mind. Also during that visit, Tom openly talked with me about many of his early experiences starting colts and working with horses at his parents’ ranch. It was plain to see as a very young man he began to establish many of the principles of horsemanship he would later share with the public.I have many great memories of Tom. However, my greatest disappointment was, due to his health in his later years, I never saw him horseback. I’ve had to rely on listening to Tom’s brother Bill, Ray Hunt, Joe Wolters and Bryan Neubert to fill in that

picture for me.

Buck Brannaman:

Tom Dorrance was an inspiration to all who ever met him. The depths of his knowledge will never be known. His love for the horse was contagious with all. We love you, Tom. I know you and Bill are playing with some colts today or maybe at a branding, so I don’t want to hold you up.

John Saint Ryan:

The last time I was with Tom, I had gone up to visit with a couple of horses (Tom never tired of me bringing him a project). It was early fall and the weather was still fairly warm in Salinas.

After a morning’s riding under his direction and trying out a bunch of things… Tom recommended… I put the horses up and sat with him under a huge tree at the side of his house. I never was shy of questions to ask Tom and I had plenty that day. He was his usual thoughtful self with a fair sprinkling of humor, and as always, he never seemed to tire of my questions.

We had been talking about feel, timing, and balance and had chewed on this quite a bit in reference to my earlier work with the horses, when for some reason I had the itch to ask Tom about “Spirit,” the third factor as he called it in his book True Unity.

I needed a clearer definition, I wanted to know how to recognize it, I wanted to have a better understanding and I wanted it now. I guess I felt I was ready for it. I felt like Luke Skywalker in “Star Wars” continually searching Obi Wan Kenobi for an understanding of the “Force”.

Well anyway, I had asked the question and was patiently waiting for the answer…I sat and waited…then I waited some more….so much so that I began to wonder if Tom had actually heard my question. But I’d been down this road before and knew how he liked to take time and consider his answer and so I kept quiet and waited.

It seemed an interminably long time and now I really thought Tom hadn’t heard my question. I was just about to start over when he looked across at me and raised his hand, then looked up at the huge tree which gave us shade on this summer day. The breeze was barely caressing the leaves, but there was movement. He smiled and said “there”. It was so clear for me in that moment, it made me shiver.

On June 29, 2003, I traveled to Salinas for Tom’s Memorial/Celebration of his life. It was a wonderful experience with people from all over the world who had come to not only pay their respects but share with us their experience and time with Tom.

I stood up and related a tale of how one time Tom helped me with a horse project, when I had become far too serious about trying to make this horse change. Tom turned it around and made a game out of my efforts, to the point where I was laughing in anticipation of what he might ask me to do next. I must admit I barely made it through the story as the reality of his passing suddenly took hold. I struggled through and I guess everyone understood and got the “drift” of my tale. I went to sit down after on my own, away from the gathering to compose myself. I sat beneath this huge tree… I looked up and saw the leaves and branches gently swaying in the breeze. It made me smile.

Thank you, Tom

Lorna Gray:

March 3, 2002. Knowing full well that Kristi and I had but three days to gear up for our trip to Cochise, Arizona, to ride with Buck Brannaman, we gladly accepted an invitation to ride with Margaret Dorrance at her home. We felt that it was a moment that we could not miss.

The sun was bright, the sky was blue, and the hills were vibrant spring green. We were on top of the world between Salinas and Carmel Valley, California.

Margaret is such a superb horsewoman; we had much to learn from her that day. We had no sooner finished warming up in the arena when Tom drove up in his golf cart. He could barely see, and his hearing was even more compromised, but he was eager to participate.

Margaret made certain he was comfortably close to the arena, and then we began to ask Tom for advice. Margaret graciously gave her clinic to Tom.

Although Tom was sight- and hearing-impaired, the rhythm of the hoofbeats was all he needed to help our horses with their people problems. He stayed with us until noon and then he was gone to take a siesta.We all knew that we had been part of a historic morning—Tom’s last clinic. A wonderful gift that Margaret gave us.

Gee Wood:

Tom sent Ray on a lifelong adventure, and Ray sent me on one as well. Like many others, I never met Tom but every day listen to the audio of his book or seek to find a new and better place with my horse friends that extends to the people around me as well. Tom may never know just how many people have been impacted by the ways he showed us, he may never have realized how important it was and continues to be, growing every day, and spreading in a worldwide network of friendships and people who are seeking better places to be with these noble creatures. I think that he would be pleased that his work is a “neverending story” among and between us all.

Kristi Fredrickson:

I had really never ridden with Tom before that spring day last year when he joined us during the “Pony Party” that Magaret Dorrance was conducting. He had participated in a Ray Hunt clinic and another time in a Bryan Neubert clinic in which I was riding; however, I’d never ridden in one of his clinics or had one-on-one time the way we did that day.

On greeting us, he ruefully mentioned his loss of hearing and sight, and he was apologetic when he had to ask us to repeat things.

In addition to asking about our problems with our horses, he asked us our horses’ names, an experience I’d never had when starting out with other instructors. I was riding my husband’s horse, named Squirrel, so when Tom asked me to repeat that name, I wasn’t sure if it was really that he was having trouble hearing, or whether he was having trouble believing that he’d really heard the name right. Or, perhaps, given his sense of humor, perhaps he just found it entertaining that someone had named a horse after a rodent, and wanted to hear me repeat the quirky name.

My problem was in transitioning up to the lope, and it was relatively subtle; the only sign I could discern was that Squirrel would switch his tail and feel tight on the transition. When Tom sent me off to do the lope transitions in a figure eight several yards within the arena, I was dubious, given his sight and hearing limitations, that he’d be able to discern the problem. However, exactly as I completed the first circle he prompted me to change direction to complete the “8,” causing me to realize that his sight and hearing didn’t significantly affect his perception. Each time I made a lope transition, he was able to determine the quality of the transition, a feat that still gives me goose-bumps as I recall it.

I don’t remember exact specifics of how he helped make my horse’s transition better that day—I do, however, remember that it was along the lines of “fix it up and wait”—I’d been forcing the transition, causing the horse to rush and get tight. I’ll always remember the amazing perception that Tom Dorrance showed on so many levels, and the lesson that diminished physical senses don’t necessarily limit one’s powers of observation.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.13