Written by Chuck Stormes

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.15

The original “saddle”, a simple cloth much like a saddle blanket, and the later pad-saddle version were held in place by a surcingle—a strap encircling horse and pad, secured by tying. The development of the saddle tree offered new possibilities for securing the saddle to the horse, using the tree as an anchoring point for the “rigging.” This seemingly simple advance paved the way for the invention of the stirrup and, ultimately, effective mounted warfare.

The outward appearance of the modern western saddle retains little resemblance to that of previous millennia, but its strong, rawhide-covered tree, adapted to roping and handling livestock, still provides a sound structure for attachment of the rigging. A strong rigging, positioned for optimum security while minimizing bulk under the rider’s leg, is the criterion for designing this crucial element of a stock saddle.

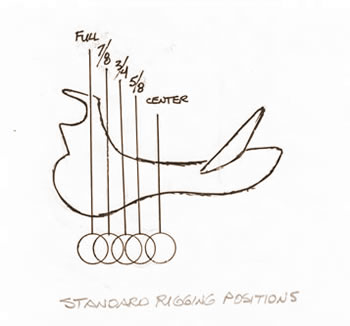

The positions in which the rigging may be mounted vary from centered between fork and cantle (center fire) to full or Spanish, directly below the fork. As the diagram shows, the designations 5/8, 3/4 and 7/8 simply refer to divisions of the distance from cantle to fork.

Since the tree is placed on the horse in the same position in all cases (where it’s designed to fit, just clear of the shoulder blade), changing the rigging position shifts the placement of the cinch and the amount of pull on the front and rear of the tree.

Center fire and 5/8 are single-cinch positions seldom used today, although they served nineteenth-century California vaqueros well. Centered rigging exerts equal force through the rigging on both fork and cantle. It requires a wide cinch—8 to 9 inches was common in its heyday—to stay in place around the fullest part of a horse’s barrel.

Three-quarter position can be used either single or double, although it offers minimal separation between the two cinches. The best choice as a single rig, 3/4 holds the fork well while still stabilizing the cantle.

Seven-eighths double is the most versatile and most popular modern rigging position. It anchors the fork well without placing the cinch far enough forward to interfere with the elbow/armpit area, even on straight-shouldered horses. A rear cinch, mounted below the base of the cantle, stabilizes the rear of the tree.

“Spanish” refers to the full, or farthest forward, position but used with a single cinch. While widely used on traditional charro saddles, full double is the standard ropers’ rigging used in American stock saddles.

Tightening both cinches of a full double rigging gives maximum stability, preventing movement of the tree even against heavy jerks on the horn, making full double the standard for arena ropers. The full double rigging’s only drawback is its tendency to crowd the elbow with the cinch on straight-shouldered and overweight horses, generally not a problem for the working cowboys who use them.

Apart from the varied positions, there are three usual methods of rigging construction used in western saddles: round or dee-shaped rings, flat plate, or in-skirt rigging.

Although all three styles can be designed to use in any of the positions, some are better suited to a particular position or to a specific requirement of horse or rider.

Round ring and dee-ring riggings are made by doubling a strong piece of skirting leather around the hardware and attaching it to the tree with screws. While simple and effective, it can cause extra bulk and restrict stirrup leather movement, especially in positions other than full.

Flat plate rigging consists of two layers of skirting with the hardware sandwiched between the two with rivets and stitching. It can be made in any position, single or double, and overcomes much of the problem of bulk and stirrup freedom while still attaching directly to the tree, isolated from the skirt.

In-skirt rigging acquired a bad reputation years ago due to poor design and construction by some of the early makers, especially some of the factory versions. When properly made, it can have the required strength, direct pull on the tree, elimination of bulk and stirrup leather freedom that the concept promised. It can be designed for any position. In-skirt rigging’s main drawbacks are inherent. Being built into the skirt, a greater likelihood of rotting out in hard use and greater expense to reline the skirts. As a result, in-skirt rigging has never become popular for ranch work but has found some favor with horse trainers.

I hope this series of brief articles on trees, seats and riggings has been helpful. Further offerings on aspects of the western saddle are being planned for future issues.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.15