Written by Chuck Stormes

There are three elements of a saddle that are of primary importance: the tree, the seat and the rigging. If all three are properly designed and constructed, the result is a good, useful saddle, regardless of style and aesthetics. If any one of these is wrong, or poorly done, the saddle is of little value. This series of articles begins with a look at modern handmade saddle trees. Articles to follow will discuss the seat and rigging.

History

The primitive wooden saddle tree, developed more than 2,000 years ago, served the same basic purpose as the modern western tree—to prevent pressure on the horse’s spine and distribute the rider’s weight.

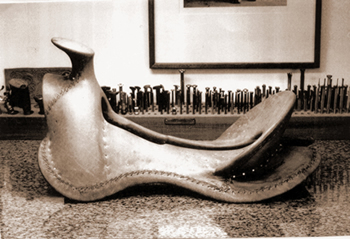

The essential parts of a saddle tree are two strips of wood placed parallel to the spine with an arch, clearing the backbone, attached near each end of the two ‘bars’ to give integrity to the whole structure.

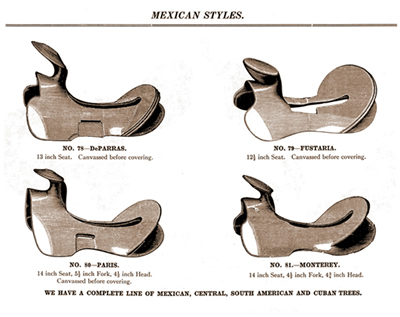

In the late nineteenth century, the American stock saddle was greatly improved by modifications made in tree design by California treemakers Antonio ‘Chapo’ Martinez, Aleck Taylor, Ricardo Mattle and others, who recognized the importance of a wider, well-shaped bar to distribute the pressure more evenly and over a larger area.

Following their lead, Bill Hubbard of the Visalia Stock Saddle Company and Walt Youngman of Hamley and Company of Pendleton, Oregon, modernized saddle tree design, making it more suited to the demands of twentieth century horse and rider. Their influence, especially Youngman’s, is evident in every high-quality, handmade tree produced today.

Construction

While early stock saddle trees throughout the West were made from natural tree forks (hence the name) and locally available timber, using equipment considered crude by our standards, the principles of saddle tree making have remained essentially unchanged for the past one hundred years, although improvements in bar design and the ability to create stronger forks and cantles have been major advances.

Most trees are now made from the lighter hardwoods, such as yellow poplar, or the stronger softwoods, Douglas fir, for example, reinforced as necessary in the fork with stronger, denser hardwoods, the variety depending on local availability.

All are dried to below 10% moisture content and selected for clarity and stability. Forks are typically laminated to improve strength through multiple grain direction. A heavy, rawhide cover is fitted wet, handsewn in place and carefully dried ( to control warping ), adding substantially to the strength and durability of the finished tree.

Fitting the Horse

Since fitting the horse is the first priority, the treemaker must have a thorough understanding of equine anatomy, the effects of conditioning (or lack of ), the changes incurred by maturing and aging, and the dynamics of the horse in motion.

Informed horsemen should also be aware of these principles and of the consequent limitations of fit possible with any one saddle tree.

The shape and structure of the bars determine how well the tree fits the horses, or type of back, for which it is intended. Apart from immature backs and horses in extreme old age, a fairly wide range can be accommodated with a well-designed tree, and a limited amount of adjustment can be achieved by varying the thickness of saddle pads or blankets. An accurate description, or photographs, of the backs that the saddle will be required to fit, along with a fair assessment of the usual level of conditioning, will provide a treemaker with critical information.

This information is usually communicated through the saddlemaker, who works closely with a treemaker or, in some cases, makes his own trees.

There are three elements of a saddle that are of primary importance: the tree, the seat and the rigging. If all three are properly designed and constructed, the result is a good, useful saddle, regardless of style and aesthetics. If any one of these is wrong, or poorly done, the saddle is of little value. This series of articles begins with a look at modern handmade saddle trees. Articles to follow will discuss the seat and rigging

Fitting the Rider.

Accommodating the needs of the rider involves choosing the appropriate combination of fork, horn, cantle and seat length from limitless possibilities. The user’s height, weight, leg length, riding style and purpose must all be considered.

Seat length is the most critical decision. In combination with stirrup leather placement and, to a lesser degree, fork and cantle choice, seat length directly affects the comfort and balance of the rider.

Briefly, a short seat places the rider too far forward in relation to the stirrup, with a feeling of tipping forward, out of balance with the horse’s motion. Trapped between fork and cantle, the rider has no chance of achieving a balanced position.

Similarly, a saddle too long in the seat causes an inability to center the rider’s weight over the stirrup, leaving the rider behind the horse and unable to catch up to its movement. However, if the low point of a longer seat preserves the relationship between the rider’s position and the stirrup leather, the result can be a classic, balanced seat that simply allows for more freedom of movement. An error in seat length toward longer, rather than shorter, is usually more forgiving.

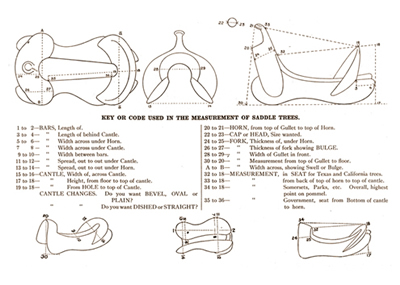

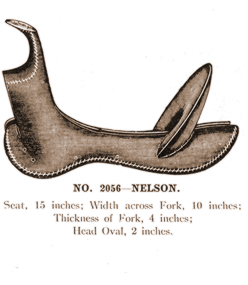

The name by which a tree is known refers only to the fork, which includes gullet height (clearance over the wither), thickness front to back and the profile or outline shape. All of the other dimensions of a tree can change without revising the name.

The confusion caused by naming trees originated in the 19th century when certain early trees, particularly well known California designs, achieved such fame that manufacturers throughout the West copied the names (although usually not the tree itself) in an attempt to increase market share.

Later, saddle shops added to the confusion by naming trees after champion ropers and high-profile horsemen (Toots Mansfield, Chuck Sheppard, Buster Welch) and copyrighting names associated with their own designs (Homestead, Packer).

As a result, tree names today are, at best, a rough guide to fork shape, and riders should work with their saddlemaker or treemaker to choose a fork shape and size that suits their requirements.

In modern trees generally, fork width varies from 8 inches to 14 inches, gullet heights from 7 1/2 to 8 1/2 inches and thickness from 3 to 5 inches. The level of support or freedom, related to the job to be done, usually dictates a preference in fork specifications.

Cantle shapes range from tall, round, old-time styles to ‘comfort’ cantles, which are low at the center with pronounced corners. Most modern cantles fall between these extremes. Heights of 3” to 4 1/2″ and widths from 11 1/2″ to 13 1/2″ cover the current range. Dish, the amount of wood carved out of the face of the cantle, can be next to nothing on a round, period-style cantle or up to 2″ in a lower, oval cantle where lateral support is a factor.

The slope of a cantle can change by 10 degrees, again according to its height, purpose and owner preference. Horn height, cap size, pitch and neck thickness present endless combinations. It’s likely that no other feature or specification of a tree receives more attention from a rider. Personal preference should be tempered by function, although for many, the main (and legitimate) purpose of the horn is to aid in mounting and dismounting.

It should be evident that anyone considering a custom made saddle should ride as many saddles as possible and consider personal preferences for the specifications of the tree. Fellow horsemen and a competent saddlemaker may offer advice based on their experience, but the customer should be knowledgeable enough to make informed decisions that will affect the saddle’s suitability to their needs.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.12