Written by Wendy Murdoch

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.31 – Subscribe today!

Contact – A Defining Quality

How many times do you end a conversation by shaking someone’s hand, giving him or her a hug or saying “keep in touch”? Isn’t it interesting that we end verbal conversations with physically orientated acts or statements? To me it means that we subconsciously acknowledge physical contact as a means of communication.

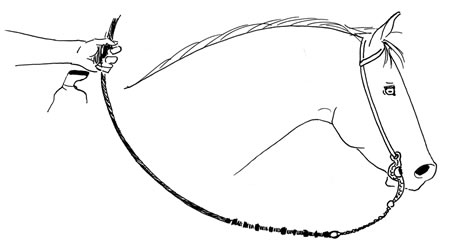

Ask a horseman what contact is and he will tell you that contact has to do with the connection from the rider’s hands to the bit in the horse’s mouth through the reins. Discussions often ensue about how short or long, tight or slack, the reins should be followed by what type of bit, or none at all, should be used. Typically, riders are judged as having “good” or “bad” hands based on the amount and quality of contact they have through the reins.

At most any horse gathering, you are likely to see all types of riders and degrees of rein tightness. It is not unusual to hear comments like, “That guy is punishing his horse in the mouth.” “That woman shouldn’t ever be allowed to touch the reins again!” “ I only ride in a halter so I stay out of the horse’s mouth.” “That person shouldn’t be allowed to ride until she can learn to quit hanging on her horse’s mouth.”

These and more are some of the comments made by horsemen and -women concerned for the welfare of the horse. The strong emotional content proves that we are outraged when we see a horse’s mouth being pulled on, tied shut, forced down or leveraged.

In fact, the mouth of the horse seems to be the focal point for defining the abusive rider. A good rider has “good hands.” A poor rider has “bad hands.” A good rider “doesn’t need the bit.” A bad rider uses lots of equipment for control of the horse’s mouth. A horse with a good mouth (soft, light) is well trained. A horse with a bad mouth (hard, stiff) has been poorly ridden.

Perhaps we use the mouth as the defining point of horsemanship because we know how sensitive it is. One trip to the dentist’s office and you can immediately identify with what it is like to have something in your mouth. The mouth has lots of nerve endings that respond to taste and pressure. It is how we communicate to others through spoken language and how we express love and tenderness by touching each other with our lips. We watch how someone holds their mouth to determine if there is a problem and are told to have a “stiff upper lip” to contain our emotions. So perhaps on an unconscious level, we attribute these thoughts and feelings to the horse. Or maybe it is easier to see what happens to the horse’s mouth than to the rest of his body?

Just as an aside, have you ever watched what horses put in their mouths? I have seen them eat everything from thistles to branches, metal and things that often give me splinters. Horses seem to chew away at a whole host of materials I would never dream of wrapping my lips around. So in another respect, doesn’t it seem quite peculiar that we are so concerned about this smooth, round metal object, the mouthpiece of a bit, that we place into the horse’s mouth? Well, I guess this is just another one of those equine mysteries…

Contact and the aids

We can’t talk about the aids without talking about contact. Why? In some way, all your aids require contact with the horse. The contact might be the sound of our voice touching the hairs in their ears or your hand on their neck. Regardless of the equipment you use, the style you ride and the type of response you are looking for, even if you are teaching your horse tricks with clicker training, you have to contact your horse to communicate and create a language of response to specific, clear, repeatable signals, cues or aids using your body, and/or anything that you have at your disposal (i.e., artificial aids such as the whip, rope, spur).

The way we work with horses determines which area of contact we use to communicate with the horse and therefore determines which aids predominate. If the horse is working freely in the arena, the voice and whip or rope are the predominant aids. If riding Saddle-Seat, the upper leg will be on the horse while the lower leg is completely off the horse. This would also be true of a long-legged cowboy on a small quarter horse but for a different reason—conformation of horse and rider.

Different disciplines use the horse and the aids differently. One discipline doesn’t use the lower leg at all (Saddle Seat) while another relies heavily on the horse’s response to the lower leg (Show Jumping). Different disciplines aren’t “right” or “wrong”; they are simply variations and nuances of using the means we have available to communicate to our horse. The differences have largely evolved over time due to how the horse was being used, the type of tack the horse was ridden in and the conformation of horse and rider. What’s important isn’t so much the aid itself but the training of the horse to the aids used. As Jean Froissard stated in Classical Horsemanship For Our Time, “Remember a truism so blatant one neglects to keep it in mind: a horse cannot obey a gesture unless aware of its sense and prepared and fit to carry out the order conveyed. Yet, unless the horse has repeatedly carried out the same command imparted by the very same aids, a rider cannot ever be quite certain of having been understood. Thus in equitation obedience is the only warranty of comprehension.” In other words, educating the horse to specific repeatable aids is more important than the manner of application.

Horses are totally capable of adapting to the different disciplines, individual application of the aids by different riders, and location of application of the aids on their bodies. For example, a short-legged person is not going to apply the aids in the same location as a long-legged person purely based on where their legs touch the horse’s body. Horses that have had only one or two riders might take a little while to understand the commands from someone with a different length of leg but quickly adapt. If the specific location for the application of the aid were so critical to the outcome, horses would never be able to adapt to different riders and short riders would never be able to ride big horses. Fortunately the horses are much smarter than we give them credit for and can adapt to the different circumstances given the chance to learn.

General DeCarpentry in Academic Equitation further discusses the application of the aids as follows:

“The place where the legs act has some influence on their effects, but it is a small one compared to the influence of the ‘manner’ in which they are used …. The completely opposed opinions of Raabe and of Fillis [two prominent horsemen in the late 1800’s] on the effects of the legs used in the region of the girth is a convincing proof of this. Raabe believed that the legs used far behind the girth produced forward movement;….. However, Fillis, whose girths used to get torn to shreds, held that this is exactly the rear edge of the girth that is the most suitable place for the legs to produce impulsion. This total difference of opinion is undoubtedly due to the fact that at the same spot on the body of the horse, Raabe used pressure of the legs, whilst Fillis, at that spot or any other, always used a tapping leg. The manner of using the legs is therefore much more important as regards the result, than the place where they are used.”

Nowadays there is something else to be considered in the location of a leg aid. The conformation of many horses has changed so drastically that the girth groove is right behind the horse’s elbow rather than several inches further back. To attempt to keep one’s legs “at the girth” would put the rider out of the classical position of “ear, shoulder, hip, and ankle.” It is important to look at the overall balance not at an arbitrary visual reference (the girth). Applying a leg aid “at the girth,” when the girth is already in front of the rider’s plumb line, might produce yet another effect due to how the rider’s weight would be displaced by using her leg “at the girth.” Finally on this subject, don’t let the arguments of Raabe and Fillis cause you too much trouble as we are not going to ask our horses to canter backwards on three legs (a feat that Fillis displays in his book) anytime soon. The basic aiding system, which I will describe later, in most instances will yield the results you are looking for. However, it is important to keep in mind that if something is not working, experimentation with the manner in which you apply your aids is recommended.

contact. Notice the even distribution of the rider’s leg along the horse’s

barrel. The knee is relaxed and well down while the calf comes in slightly below the knee, following the curve of the horse’s ribs. This rider “fits” this horse. The rider has weight in her heel and a relaxed ankle, knee and hip.

intentionally ride with their lower leg away from the horse. Lack of calf contact can also occur due to horse and/or rider conformation. When the rider’s leg is very long compared to the shape of the horse’s barrel, there will be little to no calf contact when the leg is in the correct position. If this is the case, as seen for example, when tall men ride Icelandic horses, it is better to go for a solid thigh contact than attempt to put the calf on, which will create a pinchy buttocks and heavy seat. In most

circumstances, it would be incorrect to see the leg move away from the horse like this illustration in rising trot. If the rider pushes the foot and calf away from the horse every stride when rising, then they are not rising correctly! Saddle Seat

riders would keep the leg away both in rising and sitting, which is different from when the leg is pushed away on the rising and then banging on the horse’s sides when sitting.

Contact- A Definition

In the course of writing this article, I pulled at least 30 equine books off my shelves to discover what the “masters” have to say about contact. Once again I come away a bit dismayed, confused and unsatisfied by what I have found. Nonetheless there seems to be a consensus that contact refers to the horse’s mouth. “A slight bearing of the bit on the mouth of the horse is called contact; this should be constant.” is how contact is described in the manual, Cavalry Service Regulations, United States Army (Experimental) 1914, Washington Government Printing Office. Dressage Terms Defined by Eleanor Russell and Sandra Pearson-Adams list “Contact—Refers to the relationship between the bit in the horse’s mouth and the rider’s hands. This contact can vary and depends on the correctness and balance in which the horse is moving.”

All the definitions I found seemed rather minimal except for my favorite book, Understanding Equitation by Jean Sainte-Fort Paillard. Paillard not only describes contact, he gives a clear description of the difference between the uses of the aids for Western vs. English riding. Unfortunately, this book is out of print. However I could not do justice to the topic the way he has; therefore, I will take the liberty to quote him here extensively. (Please note that Mr. Paillard refers to the horse as “it” rather than “he” as EH typically does.)

Chapter 3. The Rider’s Means.

“In order to communicate his will to the horse and to obtain obedience, the rider has no other means, as we have seen, than to make it perceive almost exclusively tactile sensations, to which the horse will have learned to react in the desired way through appropriate schooling. The reaction thus obtained is called an “obedience reaction.”

It is obvious, however, that in order to create sufficiently precise tactile sensations and to repeat them identically, which is necessary if the horse is to understand and recognize them, the rider must establish certain contacts with the horse in specific places that are always the same.

This principle is invariable. Only the means of putting it into practice can differ. In general, these means fall into one of two main categories.

The first encompasses practically all the forms of equitation that might be called “primitive” or “elementary,” but without the slightest pejorative insinuation, for when they are skillfully practiced, they can obtain excellent results in the practical and simple utilization of the horse that is their goal.

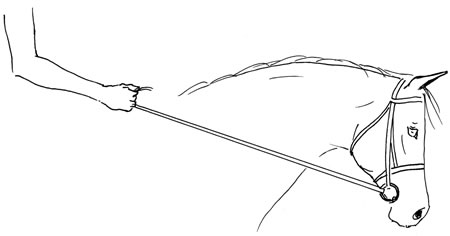

In these forms of equitation, which have always been practiced in virtually the same way wherever their goal has been the same, the rider’s actions, consequently the sensations perceived by the horse, are not constant but more or less intermittent. Cowboys, for example, do not maintain a constant leg contact due to their long stirrups and the small size of their horses, and they ride with loose reins. They grip with their legs or tighten the reins briefly and only when necessary in order to communicate simple commands concerning changes of speed or direction.

This “elementary” form of equitation obviously possesses certain inconveniences. Even if the rider’s actions are performed without brutality and with sufficient delicacy, they are inevitably rather sudden, thus unexpected by the horse. They therefore come as more or less of a surprise and can only provoke more or less brusque reactions, which, with very sensitive horses, can even be violent or disorganized. Furthermore, since they are not felt in a continuous manner, they cannot be expected to obtain much precision in the execution of the commands they communicate.

On the other hand, they offer advantages that, far from being negligible, are even of great value. During the periods between the rider’s interventions, the horse has considerable freedom of action, permitting its natural quality and instinctive gifts (gaits, agility, sureness of foot, balance) to reveal themselves, to be improved by practice, and to achieve their full development. At the same time, its sensitivity is preserved intact due to the very fact that it is not exposed to the hardening that soon results from sensations inflicted too frequently or even continually.

The interest and value of these forms of equitation lie in these advantages, since the unconstrained, natural comportment of the horse underneath the rider is always the best guarantee of the maximum exploitation of its aptitudes. This is apart from consideration of the harmony and in some cases the beauty of its postures and movements.

Nevertheless, as great as their advantages may be, the inconveniences inherent in these forms of equitation become unacceptable whenever the rider requires a higher quality of obedience, adding precision and correctness to its unconditional and instantaneous character, and also whenever he needs to exercise constant control over the horse’s performance.

Now we come to the forms of equitation that might be called “advanced” or “modern” (without necessarily investing these terms with any particularly partisan sense), and that have become necessary especially for the sporting and artistic equestrian disciplines that are most widely practiced today. The problem in these cases is to adopt a technique that diminishes or suppresses the inconveniences of the elementary forms of equitation, while safeguarding as far as possible their advantages.

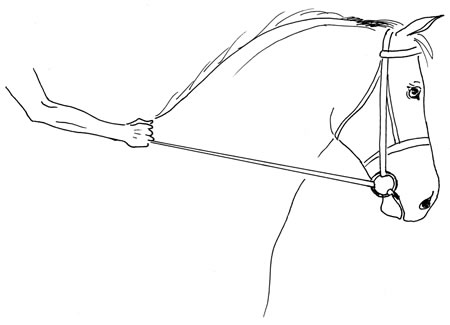

Common sense dictates the only solution capable of eliminating the inconveniences: a behavior that permits the rider to constantly communicate his will to the horse. Since his will is expressed by sensations resulting from the actions of the aids, this obviously implies that these sensations must be constantly perceived by the horse, therefore that the rider’s aids (hands and legs) must be constantly in contact with the relevant zones of perception.

In this way the horse constantly feels the aids, even when they are not active. The rider’s actions, even if they are sudden, merely modify a previously perceived sensation and no longer come as a surprise to the horse, thus eliminating brusqueness and disorganization in the reactions they are designed to obtain. Moreover, they can be constantly modulated according to the horse’s reactions, thus enabling the rider to control them and eventually to achieve precision in the horse’s performance. The idea of contact is henceforth clearly established. For once (as is not always the case with equestrian terms!), it happens to correspond to the dictionary definition of “contact”: the state of two bodies in touch with each other.

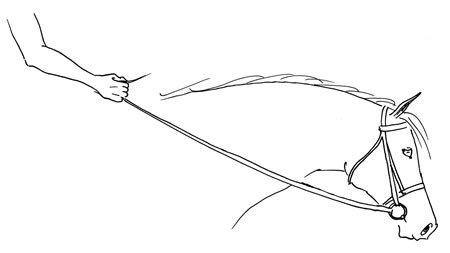

In order to establish contact between the rider’s hands and the horse’s mouth, it is necessary and sufficient for them to touch each other through the intermediary of the reins and bit.

In order to establish contact between the rider’s legs and the horse’s body, it is necessary and sufficient for the legs to be in a position where they touch the horse’s body.

It should be needless to add, although it is perhaps preferable to do so in view of certain opinions and erroneous beliefs, that the establishment of the contacts in no way implies any sort of tension of the reins, or any kind of pressure of the legs, except the minimum degree necessary for their continued maintenance.

Let us insert here one minor observation. When one speaks of contact, riders too often think only of the contact established by the hands. The contact of the legs is, however, every bit as important and for exactly the same reasons. Should not the traditional military order, “To your reins!” still used during cavalry training in France, be replaced by “To your aids!”? It would ring out just as well in a riding hall and would have the immense advantage, at the moment when the riders are asked to take command of their horses, of creating the reflex of really taking command, that is to say, of adjusting reins and legs, and of thus establishing the contacts – note the plural- necessary in order to command clearly and correctly.

It now remains to study the question of whether or not this manner of action based on constantly maintained contact risks destroying the advantages that, as we have seen, result from its suspension between two successive actions. We must therefore examine separately the case of the legs and that of the hands.”

As a result of reading Mr. Paillard’s clear and thoughtful description regarding contact I would like to refer to contact in the more general sense according to Webster’s Dictionary. Contact is defined as “the act or state of touching or meeting [two surfaces in contact], the state or fact of being in touch, communication, or association with.” Therefore any time or place where the human body comes in contact with the horse is contact. We can then discuss specific locations of contact i.e.: with the hand or reins, leg or seat. It is also important to recognize that the hands can have intermittent contact while the rider’s seat has the most continuous contact with the horse.

The rider’s seat, while having the most profound influence on the horse, is perhaps considered the least. In almost every book I looked at for this article, there is a discussion of the aids, which include the hands and legs. Some books include the rider’s weight but rarely is the seat discussed as a separate aid. I am not sure why. Perhaps this is because the “masters” spent so much time developing the seat, they did not consider it as a separate aid but integral to the application of all the aids. However, if you listen to Arthur Kottas, retired 1st Chief Rider of the Spanish Riding School, as he teaches, he always refers to the “seat, weight, leg, rein” and how each of these needs to be adjusted for changes of direction and lateral movements.

The seat of the rider is the greatest area of contact a rider has on the horse when sitting in the saddle. Even when you drop the reins you are still in contact with the horse through your seat as long as you are on the horse. In fact, once you swing your leg over your horse’s back, your seat (whether it is in the saddle or not) has more effect on the horse than your hands ever will. Standing up in the stirrups does not negate the effect of your seat. For that matter it might even make it worse if you are standing more in one stirrup than the other. So no matter what you do, as long as you are on that horse, you can never give up your seat. You can throw away the reins and feign that you no longer have contact with your horse, but you would only be kidding yourself. The horse would know different.

Not only does the rider’s seat cover a larger surface area on the horse, the effect of the seat is much longer acting. To prove my point, think about the last time you did something that hurt your back. It might have only taken a moment—picking a bucket up wrong, bending over, falling off and landing on your back. But how long did the aftermath last? One day? One week? Two months—years?

Now let’s consider the horse. If you put a badly fitting saddle on his back and/or ride him for two hours like a lump and “stay out of his mouth” either by keeping the reins slack or using a halter, you may think you have been kind to your horse because you haven’t had any contact on his mouth. But what has happened to his back for those two hours? Have you ever noticed that the next day he might not want to be saddled up again? He isn’t so cooperative on your next ride or he drops his back when you climb into the saddle? But you “stayed out of his mouth” so everything must be “OK.” Right? The contact you might have had with his mouth for the brief period of your ride ended when you took the bridle off—the contact you had with his back may have lasting effects for one night, a week, a year. Who knows how long?

I am not saying that hanging on to the horse’s mouth is right either. Those dressage horses that are badly ridden are put between two evils: the driving demands of the seat, leg and spur (most likely with a bad-fitting saddle) and the traction on the reins. And of course there is everything in between depending on what discipline you look at. However, to be a considerate horseman or -woman interested in riding your horse well and to the best of your current and future ability, it is important to think about what is really happening when you ride and not simply accepting some traditional dogma (regardless of the discipline you learned it from) in your riding and training. Therefore when considering the aids, we must think about the contact we are making with our horse through all means we employ—seat, weight, leg, rein, voice, and even our very presence.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.31 – Subscribe Today!