Written by Terry Church This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.45

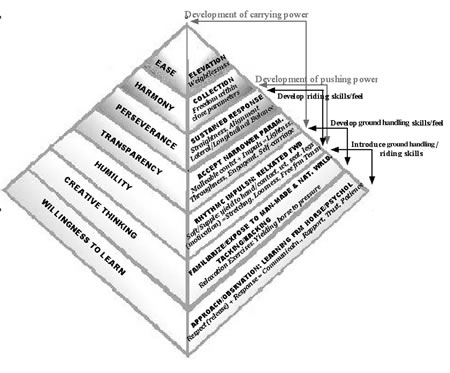

Part III of the Pyramid of Training presented some ideas correlating to tiers 3 and 4 and pertain to the horse and rider (or driver) after the horse has been started under saddle or harness and exposed to a variety of environments.

While specific examples and exercises were referenced in the past two articles, our efforts to achieve rapport and partnership involve paying attention to the internal dynamics that we feel and sense between our horses and ourselves, making the written word an imperfect guide to exploring firsthand realms we cannot see with our physical eye or manipulate with our hands. It is the time and effort we put into developing our sensitivity, awareness, communication skills and feel that allow us to notice the positive changes that come as a result of understanding our horses better. In this way, we give them reason to trust in us and to become more at ease inside their own skin. If we have been able to support their ability to develop an internal process by which they can assess their surroundings and learn to feel confident wherever they are, they are freed up to pay attention to us and sort out what we ask of them. For all of this to happen, we need to have been willing to go through our own set of processes by which we learned to accept responsibility for the quality of the relationship.

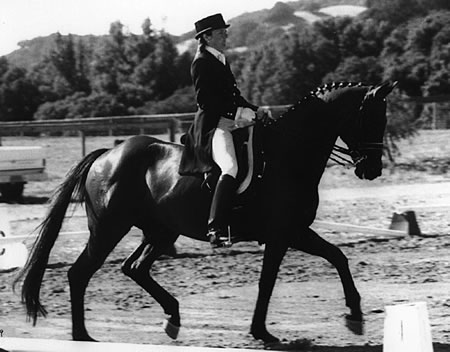

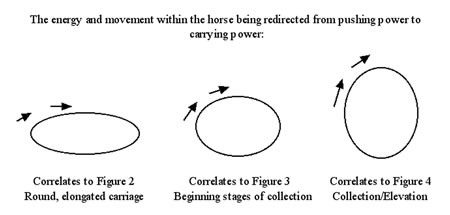

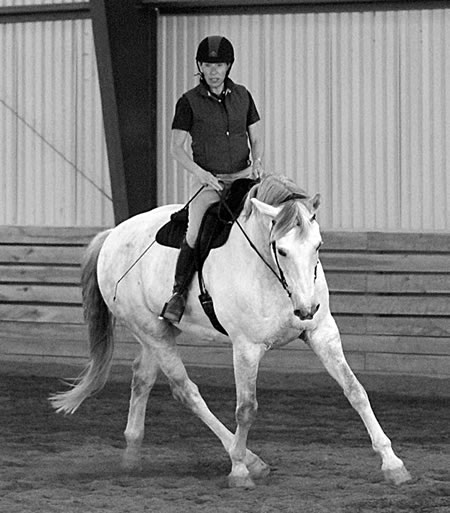

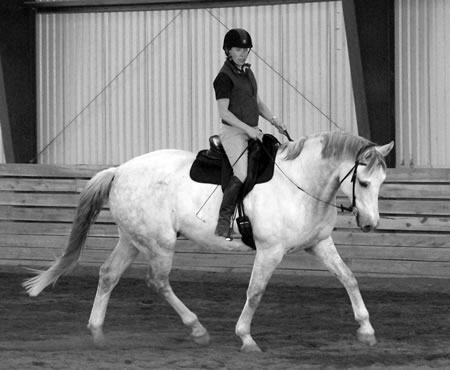

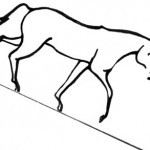

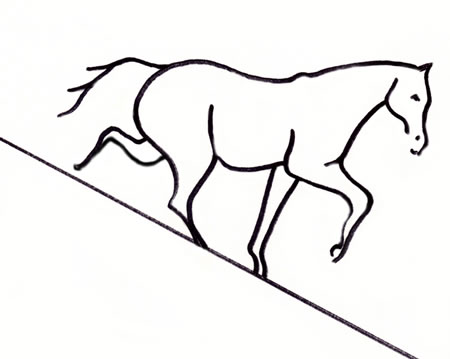

Accepting responsibility does not mean that we are always at fault, or that we are the cause of our horse’s every inability to cope. Some horses are emotionally complicated and present greater challenges for us to sort out. Others have histories that take longer to work through. While oftentimes frustrating, perseverance rewards us with great opportunities to develop ourselves as individuals, daring us to exercise and expand our physical skills, but also our patience, empathy, honesty, adjustability, self-reliance, and our ability to problem-solve through creative thinking, all the while learning to see situations from a perspective other than the one with which we routinely view the world. In addition, we continue to integrate the seemingly opposing qualities of firmness and softness, grit and sensitivity, the refined focus that detailed work requires alongside a broad awareness of the big picture and the meaning behind it all. How remarkable it is to work with an animal that draws out the many traits and abilities latent in each of us, the balance and synchronization of which allows for clarity and harmony in the way we communicate. Figure 2-4: Note the varying degrees of collection in these horses as the weight is progressively shifted to the hindquarters, allowing the forehand to elevate naturally. As the horse learns to soften to the contact of the rein and yield through the full length of its body, all of the energy output generated by the hindquarters to achieve forward “pushing power” is redirected to encourage the hind legs to reach farther underneath the belly for more “carrying power.” This reflects a very different process than slowing the horse down or holding him in with the reins.

As the work becomes more demanding, our relationship continues to evolve, but for our horses to remain happy as more is expected of them, rapport and partnership need to remain the basis for how we evaluate our success. Although “moving up the pyramid” has its own set of challenges, I have seen and experienced that performing more difficult maneuvers is really the icing on the cake for the person who has been willing to build a solid foundation based on mindful interaction. Our ability to become familiar with whatever activity we’re engaged in, to grapple with every dilemma, to work through our own emotional responses to those dilemmas, to develop the fine motor coordination that really good riding and handling demands is, for the most part, learned in the bottom four tiers, if you will. Our ability to ride the upper levels (if we’re dressage riders) or more demanding jobs with proficiency comes as a result of the years we have spent prior to this point. A trainer of mine used to say, “Bring ten horses to second level and you can ride Grand Prix.” In my own experience I have found this to be essentially true. The more horses we can work with, the faster our learning curve and the more thoroughly we can fine-tune our feel, develop broad perspectives and widen our range of skills. It is also true that as the work becomes more demanding, our understanding of how to prepare our horses for that work becomes more important. In dressage, the “work” involves performing upper-level movements. In jumping, it involves higher fences, more complicated course work or cross-country riding. In the western disciplines, it might involve reining or roping or stock horse work. For trail horses, endurance horses and ranch horses, it might include becoming more versatile, tackling rougher terrain and enduring longer distances. More difficult work demands greater strength, maneuverability, responsiveness, and agility that can be sustained. These abilities require the horses to collect and expand their bodies interchangeably, and for their movement to be initiated from the hindquarters. Any horse will perform a job better with adequate strength. Overall, every horse’s longevity and usefulness is increased by doing its job without tension. As mentioned previously, a muscle that is not relaxed cannot be adequately strengthened, and so like us, our horses fuse and balance seemingly opposing but inherent abilities such as strength and softness, relaxation and energetic responsiveness, lengthening and shortening, bending and straightening, sensitivity and calm confidence, rhythm and adjustability, elasticity and force of action.

As we become more skilled, the temptation is often to “get the job done.” It is easy to want to superimpose what we want from our horses onto them, as opposed to continuing to set up situations that allow them to find for themselves what it is we’re asking of them. While sometimes necessary for dealing with a task at hand, the strictly “get it done” approach limits us to our physical skill. Putting depth into the way we work requires us to think more creatively, to consider the consequences of our actions, and to continue gaining a broader understanding of what our horses need from us in order for them to respond with confidence. An inherent athleticism combined with a natural eagerness to accept leadership makes horses ideally suited to perform whatever job we might want without needing to be forced or “made” to do it. We can instead continue to learn how to create situations that allow them to make their own decisions that happen to concur with what we have in mind. It’s a concept talked about among many horsemen, and one that has been alluded to in every valued dressage manual for the past several hundred years. Yet how often do we actually get to see this idea expressed into action, particularly in the show ring? How well our horses accept our lead without us forcing them to do so depends on the kind of relationship we’ve established with them and how well we communicate our intention. Our ability to communicate largely depends on how well we understand the horse, but also how well we understand the various components of the thing we’re asking for. For example, in order to ride our horses straight, we might use our reins and legs as guideposts so that the hind feet track directly behind the front and the shoulders are kept in alignment, neither leaning in or out, on a straight line or on a circle. But if we first understand that softness throughout a horse’s body (resulting from a process of releasing tension and tightness) combined with forward movement creates an even stride in and of itself, then we can allow our horses to realize a straightness they already had inside themselves before adding unnecessary amounts of rein and leg contact. Our ability to elicit straightness from the inside of our horses rather than superimposing it from the outside requires us to know how it occurs naturally, to then notice when it is taking place, and finally to understand its significance so that we allow it to continue. To learn this means we are interested in more than just the immediate gratification that comes with “making” our horses straight. It means that we enjoy witnessing how moving straight in a fluid manner is pleasurable to them and reflects who they are. It’s a far different experience than the mechanical, sometimes irritable response that comes “because we said so.” While that approach may get us the “thing” we want, the other gets us the “thing” we want and rapport because we are not restricting, confining or overcontrolling their every move. Collection can be achieved in the same way. Collection occurs when the bulk of the horse’s weight is shifted toward the hindquarters, enabling him to gather his body for greater maneuverability and actions that require strength. The suppleness and softness achieved through allowing him a process by which he learns to release tension throughout his body (Part II) needs to continue as more “carrying power” is required. Achieving carrying power is also a process that may require patience for us “Type A’s,” allowing our horses time to develop their unique muscular capacity. (See Figures 2-4) One way of achieving degrees of collection is by using a figure as “simple” as a circle or a bending line (See Figure 5). In a turn, the bend in our horse’s body combined with the forward movement and soft feel that we have learned to maintain keeps him supple laterally (along the sides). Riding forward and soft also keeps the back “up,” or free from tension longitudinally (over the top line). If we know how to sustain our horse’s balance so that he is neither falling in nor out of the circle with the shoulders or hindquarters, the inside hind leg will reach farther underneath the belly because 1) there is no tension or tightness to restrict the stride, and 2) because, on a bending line, the inside hind leg has a shorter travel distance than the outside hind leg. It compensates for this by reaching diagonally in front of the outside hind leg (allowing the stride to remain even), and subsequently accepting the bulk of the horse and rider’s weight. Key: the “secret” to a horse’s ability to collect without the tension and stress often associated with this action is maintaining softness, laterally and longitudinally. The smaller the circle or bending line, the more acute will be the bend in the horse’s body in order to match the circumference or outline of the arc (See Figures 6-7). This causes yet more reach with the hind legs and a greater proportion of weight to shift to the hindquarters. This does not mean that it’s a good idea to start out riding small circles. It means that smaller circles generate a greater degree of collection. Start big (at a walk, albeit a forward walk) to reduce the risk of strain and irritation. Again, only a relaxed muscle can be adequately strengthened and thoroughly benefit from this type of exercise. Only a horse who has been given room (release) to move freely within the narrower parameters required by such a movement (or any other job) can remain relaxed and happy with the work he is being asked to do. This means there is a lot for the rider to learn and prepare for before successfully applying these concepts.

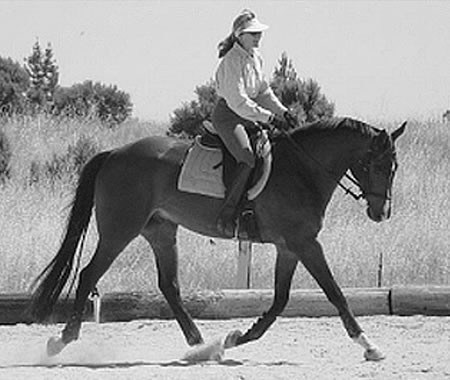

Hills are another tool that can be used in a variety of settings to help our horses learn to adeptly collect their own bodies. Again, if the rider understands how to keep their horses supple, soft and forward, the hill does the work of helping the horse find his already inherent ability to collect himself (See Figures 8-9). The better the horse can do this, the more level his body becomes, making the hill easier to ride. Maintaining softness throughout the horse’s body (throughness) ensures that tension and bracing are not used to compensate for a lack of strength. Dressage riders are offered a host of additional movements and figures to help their horses remain supple while developing the strength and agility for collection. If we would use those movements in the way they were intended, rather than pulling our horses together with the reins while pushing them on merely for the sake of doing the movement, there would be far less suffering among dressage horses, particularly those used for competition. Riding movements according to how they were intended requires the same depth of understanding that reaches beneath the surface of a physical skill required in any

discipline. Ease, written on the top left face of the pyramid, might be considered a mantra for us dressage riders, reminding us that tension, strain, trying too hard, forcing things to happen, “cramming and jamming,” and punishing our horses for what they have not been able to do for us have no place in beauty. By the same token, the common appeal to “ride our horse’s every stride” does not have to mean “micromanage every step.” There is a difference between controlling each foot and being mentally aware of where each foot is underneath us, just as there is a difference between executing an agenda and communicating our intention. In other words, in working to develop our horses as athletes, we have the choice of doing so in a way that fits an image of what we think an athlete should look like, or we can do so in a way that allows them to be the athletes they are. One approach compels us to place each stride, the other teaches us how to prepare ourselves so that the horse places his own stride where we want because he already knows where his feet are. One approach is born out of a fixation on a pre-set idea, the other keeps us focused on what is actually happening. One approach leads to coercion, the other to leadership. Coercion makes the horse tight in the same way we would react if a dancing partner pushed and pulled us around, making a bad attempt at leading. While coercion may indeed achieve submission, giving the horse time to learn to follow our intention is what allows for partnership, and so reflects the true art of horsemanship.

And yet submission, not partnership, is the word highly revered in the dressage world and written on every dressage test. Years ago I owned a horse who would not submit to any amount of training or influence from more than one internationally renowned trainer. After years of beating my head against the wall, I now remain eternally grateful. He steered me onto a path that led toward engaging in more mindful relationships. Since then, I have not come across a horse who was not interested in partnership if I would but learn to present myself in a way that he needed in order to trust and respect me. Interacting with various personalities, breeds, confirmation types and behaviors has brought out different traits or qualities within me that I needed to learn more about in order to better interact with each horse. With some I had to learn to slow down, with others I had to learn to get there earlier. Some taught me a greater degree of softness, others pulled out of me a need for clarity and firmness. All have taught me that I needed more patience and “thinking time” before acting in a way I would later regret. Every other quality I don’t yet have at my fingertips means that I might still feel awkward and uncomfortable as I grapple with how to be more appropriate with each individual. But there is nowhere else in my life where I continue to learn such important life lessons with the same amount of love, loyalty, tolerance, forgiveness and honesty. Certainly nowhere else I have enjoyed as much.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.45