Written by Terry Church

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.41

The idea for the “Pyramid of Training,” or training scale, was first conceived in Europe by a General von Redwitz and a Colonel Hans von Heydebreck in 1912, and was later included in the official German training manual after W.W.II. Today in the United States, it is required reading for all certified dressage instructors. Briefly, the training scale was intended as a written progression of steps to be taken in schooling the dressage horse, “start to finish.” However, a horse’s physical development, his mental understanding of what is being asked of him, and the ease with which he potentially relates to the human can be sought after in any riding style or discipline. Therefore, the pyramid can be applied to any horse whose work demands athletic skill, and it can be studied by horsemen and women who wish to increase their level of understanding (at least intellectually) about the bodybuilding phases a horse must go through to perform increasingly difficult actions or movements.

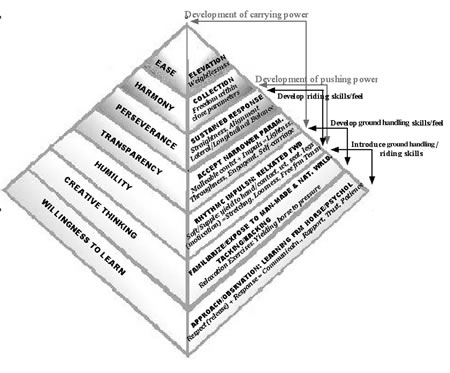

In recent years, the Pyramid of Training had various forms. One that was commonly used had seven tiers as shown below in Figure 1.

The tiers represent the progression of “training” in phases. Each tier (or phase) contains a concept or action that represents a desired outcome for that phase. The phases are listed from the bottom upwards, as you would walk up a stairway from the ground, alluding to the importance of establishing a foundation before moving to the next level of complexity.

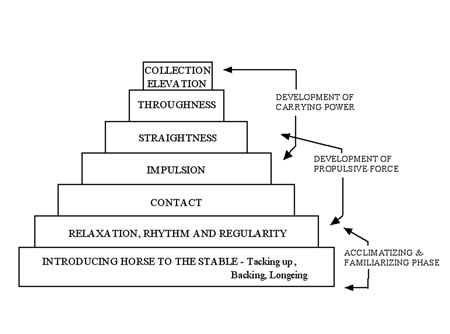

In 2007, the United States Dressage Federation (USDF) standardized and published an “official” Pyramid of Training. It has six tiers as shown in Figure 2, below.

As you can see, it is a bare-bones version, streamlined to fit nicely on a two-dimensional page. But even if you understood the meaning behind the words used to describe each phase, you would not necessarily have the understanding it takes to apply their meaning, let alone do so in a way that allows the horse to be happy with his work or remain happy with you in the process. In addition, this pyramid does not readily help everyday horsemen understand how it relates to them. Although dressage is touted to be the ultimate example of athletic achievement while maintaining harmony between horse and rider, many of today’s training methods for the dressage horse (as well as for other disciplines) do not, in fact, set an example of the mindfulness and supportive calm alluded to in writing. This is true in daily training as well as in the competitive arenas, as most of us have witnessed and oftentimes experienced for ourselves.

In Figure 2, Rhythm is listed first (bottom tier). One argument for this is that rhythm must be established in order to have ultimate relaxation in movement. While true in and of itself, rhythm is one piece of a very large pie. It is only established after the horse has been started under saddle or on a longe line with side reins (according to traditional dressage methods), and then again only after the horse understands the forward aids to the degree that a consistent tempo (pace) can be sustained on a circle. The pyramid does not acknowledge how relaxation can happen for the horse before being ridden, or how it can happen if you opt not to longe with auxiliary equipment, such as side reins or draw reins.

Another argument for the current rendition of today’s pyramid is that it is meant to represent the riding horse and only the horse (as opposed to the training of the rider). But I believe that an important opportunity to engage a broader spectrum of horsemen has been missed — horsemen who might otherwise gain valuable insights about their equine partners. In addition, if the basic and most constantly visible formula by which all United States dressage instructors will be trained and certified does not speak to the importance of the communication and rapport that must be established between the horse and human before any “training” takes place, then the ideas most aggressively promoted are ones that refer to mechanical skill, rather than feel — of image, or what it’s supposed to look like, rather than a true, deep and broad understanding of “why,” “how,” and “whatever for.”

The lack of adequate representation within the dressage community for a relationship-based approach has spurred many (no pun intended) to seek other ways of working with their horses and to question traditional dressage trainers and their methods. It is no longer enough for many of us to see well-intentioned riders give their horse a pat after a training session, feed him carrots, and coo into his stall as proof that they’re all about having a good relationship with their horse. Nor is it enough to see a horse going around with his head tucked, performing highly gymnastic movements while at the same time grinding its teeth and wringing its tail. Although having love for the animal, providing care, and striving to be the best rider one can be are vital prerequisites to goals that have value, in and of themselves good intentions do not give birth to the kind of understanding that real partnership requires — i.e. the kind of partnership that benefits the horse as much as the human.

I am both that “traditional dressage trainer” and “one who sought a different approach.” My hope is that because I have spent years in the integration of “traditional” and “natural,” I can offer some clarification for those who are struggling to find a way to bridge two seemingly opposite approaches. While the written word does not always translate into being able to execute the suggested ideas in a real-life scenario, my goal is to help the reader better understand the Pyramid of Training by suggesting a feeling sense behind what the words on the page mean. In this way, readers are encouraged to navigate their own experience, and to think while they do. I also hope to help clarify some misconceptions that pervade the dressage community and perplex those trying to incorporate dressage principles into their work with their horses — such as the meaning of “contact,” for example.

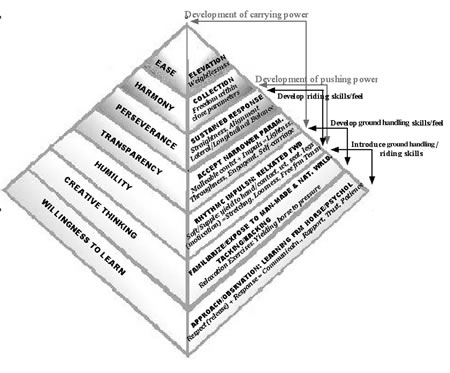

As seen in Figure 1, the pyramid that was used in previous years does refer to what is called the “acclimatizing and familiarizing phase” of the horse. But in an effort to translate the current pyramid into the language of the everyday horseman, I drew a modified version in Figure 3. It is not a definitive “how-to” on “training.” It is a guide; an outline meant to encourage discussion and participation. It is in progress, just as I continue to be, and reflects my experience to date and what I have observed in many of the people I work with around the country.

There are three sides to this pyramid. As in previous renditions, each side or face is divided into tiers, representing learning phases. On the right face, the top text-line in each tier alludes to the outcome that will be aimed for within each phase. The line below it (in italics) describes the prerequisite to achieving it. These prerequisites could also be identified as the positive qualities, or a feeling sense that begins to emerge as a result of taking certain actions that benefit the horse and further the person’s understanding of “why,” “how,” and “what for.” These qualities are both a goal and a means to a goal, and are necessary for the person to learn to feel for in order to achieve the true meaning of the word or words written above it (desired outcome). The words correlating to the left face of the pyramid suggest a mindset or sense that the person will develop and use as the backbone of their work in order to maintain rapport with their horse along the way. To the right of the pyramid are phrases that correspond to the back face (the side you cannot see) and speak to the general purpose and intent of each phase. The words in black refer to the person. The words in gray refer to the horse.

The important thing to realize about this printed version is that, in reality, each concept is not limited to its tier, nor are the concepts always absolute. For example, it is possible to have the horse feel weightless when we reach for a leg to pick out a hoof if the horse has understood how to balance on the other three legs. And it is possible to feel how straight in self-carriage our horses can be while trotting forward freely with their noses stretched to the ground if they have understood how to not lean on our hands for support, but instead reach up farther underneath themselves with their hind feet, marking the onset of engagement. In fact, it is feeling the emergence of these “higher” qualities when we first begin working with our horses that informs us about how we will want things to feel more consistently later on.

Subsequent articles will discuss more fully the meaning behind the words and concepts in each phase, while this introductory article will be limited to the first (bottom) phase in an attempt to do justice to the complexity of the pyramid.

The purpose of the first phase as it is written in Figure 3, is to draw attention to and articulate the importance of laying a good foundation for our work and continuing partnership with our horse(s). When we begin any endeavor, there is a certain time it takes to learn the mechanics or the “how-to” of a thing. Working with horses is no different. How to be around them, handle them, and ride them are all processes that require putting our desire to learn into physical effort. It is a vital part of the process, and at the same time only one part of the process. Once we begin to be able to “do” some things, we are hopefully motivated to dig deeper and learn how to “feel.”

In my own experience, developing feel comes from the mindset with which I approach my equine partner, and allows me to prepare myself for the level of emotional (as well as physical) responsibility that I agree to accept in the relationship. Any endeavor I undertake can be done and maintained on a superficial basis (to become skilled at the mechanics of a thing and leave it at that); or be born out of a willingness to dig deep and face what it is that keeps me from knowing myself and thereby truly connecting with another. One requires maintaining an ego. The other requires humility. The easier path, the more common road, is about the visible world of image: how I try to appear to others, and my reliance on things, such as winning blue ribbons in order to feel adequately valued. The harder, less traveled and often unclear path, is about the invisible realm of establishing trust and finding meaning.

I have found that the kind of connection that leads to trust comes as a result of the respect I have for both myself and another, in this case the horse, who has its own set of perspectives, view of the world and experiences I must acknowledge and converse with, rather than force into my way of seeing things. In my rendition of the training scale, I mention “release” as a prerequisite for achieving rapport and trust. Release, or giving the horse relief from pressure, might come in the form of easing tension on a lead line, a rein, or a leg. Or it might come in the form of stepping back, taking a moment, walking away, or giving myself time to cool down when I’m frustrated. It’s about allowing the horse to have a moment to soak, to be who he is, to feel relief when he’s made a good try, or to have some space to settle. It’s also about allowing myself to have a moment to soak, be where I am in the process, feel relief when I’ve made a good try, or to have some space to settle.

Release is not merely a physical thing. The motive for the release comes from an emotional willingness to let go—of my agenda or of trying to achieve outcomes—and to ultimately trust that if I do the best or most appropriate thing I know how to do in each moment, my desired outcome (which I hold in the back of my mind) will come about. It has been interesting for me to note that when I can put myself in the frame of mind of not trying too hard, or of stepping out of the way as much as taking a specific action, what I wanted to have happen, happens in a better, more timely way than I might have imagined. Learning to give up my agenda allows me the opportunity to focus on where the horse is each day and each moment, instead of struggling with where I think he should be. It doesn’t mean I give up my dreams, the thing that I want, or the ideal I’m striving for. It means I’m willing to be flexible with my focus and learn to address whatever is presenting itself in the moment —which means I’m trusting what will come about if I do.

For me, the ability to actually put these ideas into practice includes being okay with not having all the answers, so that each time I embark on a new project, I become open to learning from this animal that I’ll be spending a great deal of time with. “Observe, remember, and compare,” often iterated to me by the great horseman, Tom Dorrance, is a key triune concept that helps me stay objective as I go about the “things” that are to be “done” with my horse—along with maintaining the curiosity of a beginner, never assuming I know everything. This mindset allows me to try new things, to experiment, and to be okay with making mistakes. Lots of them.

What many of us “do” at this stage might include round-penning, familiarizing our horses with being touched all over their bodies with our hands, ropes, halters, and lines until they are relaxed and confident, leading from both sides, leading up close and far away and from the back of another horse, driving from the ground, having them be alone with us as well as allowing them time turned out with others of their own kind. If we are experienced, we’re also already incorporating other ways of exposing them to the world and incorporating aspects of phases to come. If we’re more novice, we’re keeping things simple and spending a lot of time becoming coordinated with our bodies and whatever tack or equipment we’re using while honing our riding and handling skills.

This phase can be the most difficult for a lot of us, as it contains the foundation for a perspective we will carry with us throughout all the phases. The time it takes to develop the rapport, build the trust, and get the response we want from our horse will depend on us and how much or little experience we humans have with whatever scenario presents itself, and whether we’re working with a young horse, a “made” horse, or a difficult-to-handle older horse that came to us with a lot of history and baggage. For the experienced, it can take less than an hour. For the novice, more than a year and far beyond.

We begin with the time it takes to understand certain concepts. Then there is the time it takes to try them out on our horses, to not get it right, to be confused and to have our “partner” not respond the way we think they should or in the way we think we’ve asked them to. Then there is the time it takes to either keep trying or to keep trying different tactics—or to find someone who can help us figure it out. Concepts we thought we understood at the beginning, change meaning and transform with each experience, and we’re dismayed when we realize that we know much less than we originally thought. Even after we begin to get an inkling of what it actually feels like to ask for what we think we want, there are ever more complex physical coordination skills we must hone along the way.

During this foundational phase, we will oftentimes feel the most daunted, the most elated, the most inadequate, the least understood, the most afraid, the most impatient, the most frustrated, the most inspired, the least compassionate—emotions we will revisit again and again throughout the coming phases. Our old habits will oftentimes be useless or in the way. Every reactive button attached to an old experience that is tied to our past and has nothing to do with the present will be pushed, because we’ll be tricked into feeling that the emotion that arises has everything to do with the present—and surely must be the horse’s doing. Then, we’ll beat ourselves up each time we realize, yet again, that what we thought was true really isn’t after all. And so, the time we spend each day is, in the end, not for the horse, but for us, although most of us will not see it that way until after we’ve gained some experience and acquired perspective. That, too, will take time.

It’s hard-core learning at its finest.

And the purpose for all that time? Developing patience, but also self-empowerment. Self-empowerment because, even when I seek support and assistance from others, no one besides me can walk my path or learn to walk it mindfully.

The really good news is that if we can bear to go through it, stick with it, do our best to do right by ourselves and the horse, and find whatever kind of support we need while we go through the process, we will come out not only better horsemen, but better humans. And needless to say, the horse, our teacher, will be grateful—as might the rest of the world, both inside and around us.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.41