Horse Gear & Makers

The Mecate Master

Written by Doreen Shumpert

The horsehair mecate is as traditional to Spanish-influenced horsemanship as fireworks are to the Fourth of July. However, master craftsmen like Doug Krause, who can produce modern-day quality hair ropes, aren’t so commonplace. It’s artisans like him that keep tradition – and history –alive and pure for generations to come.

For Krause, it’s all about tradition. His former modest shop in Eaton, Colo., was wallpapered with traditional cowboy prints and movie posters, and traditional western tunes drifted from the radio. He was as much at home there, amidst the horsehair and leather, as he was in his Victorian-style house out front. These days, he’s relocated to Clements, Calif., and is employed by Ricotti Saddle Company. Although his location has changed, his commitment to excellence and cowboy tradition has not.

Krause hasn’t only mastered mecate making; he crafts custom saddles and does some of the most beautiful, colorful horsehair hitching around. Recently, he produced a custom saddle containing more than 400 carved flowers and a hitched horsehair seat that sold for $50,000.

But these days, he focuses on his mane-hair mecates. Because of the rise in popularity of reined cow horse and snaffle bit events, the Spanish traditions of bosals, slobber straps and even the two rein (part of the graduation process from hackamore to bridle) are migrating eastward from their California roots and increasing demand for good mecates.

Origins

Krause has always been around horses, and he tried a little high school rodeo. Around 1973, he braided his first bull rope, and that began the journey. Soon, his interests expanded into horsehair hitching, which he taught himself, and a four-year saddle-making apprenticeship.

As for mecate making, he was influenced by the ropes of Blind Bob Mills, who learned from his predecessor, Blind Sam Champlin. And those weren’t just nicknames.

Incredibly, both mecate makers were blind and produced their fantastic hair ropes by feel alone. While Mills and Champlin each faced a unique challenge, the main trait they had in common with all great mecate makers is a thorough understanding of usage and tradition.

“With a good hair rope, by just using your fingers, the signal travels from your hands to the bosal,” Krause said. “It’s like a massage to the horse. You don’t have to lift and pull so much. Training cues can be more subtle. I think that’s why many great trainers are into training horses in this tradition.”

It also explains the horsehair mecate’s edge over a synthetic mecate, as the latter tends to absorb the signal, and the rider has to lift his or her hands and pull more to transfer the signal to the horse. Traditionally, a mecate should be the same size or a size smaller than the bosal and from 22 to 24 feet long.

The Process

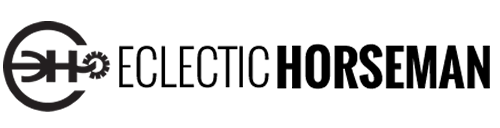

“Picking” hair

When the hair arrives, it is washed and conditioned, then run through the picker – a process like carding wool. Krause squirts the hair with water to tame static, and then the picker’s big drum combs the hair and separates the fibers (photo 1). A good mecate is composed of mane hair because of its soft, smooth fibers. Tail hair is coarse and only used in hitching. Most of the hair comes from Mongolia, and harvesting it from both living and deceased horses is a profitable market for Mongolians. Interestingly, the breed of horse can affect the texture of the hair.

“The draft and cold-blooded breeds have coarser hair, and the warm-blooded and hotter breeds have finer hair that’s easier to work with,” Krause said. “We can control the feel of a rope based on where the hair comes from.”

Hair is not dyed for mecates – it is only dyed for hitching– because the colors will oftentimes run. Krause said people who want colored mecates usually choose synthetic ones. He does make a few synthetic mecates the same way he makes mane-hair mecates to keep the same feel. But overall, they aren’t as popular.

“Most people who ride with hair ropes are very traditional,” he said. “The West Coast usage goes with the training philosophy passed down from the Spaniards. We can create different looks with color choices, however, and the way we put them in. Many reined cow horse folks like a lot of white so the rein action is easy to see, but the western pleasure people prefer black to minimize movement.”

Tying the mecate

“There are several correct ways to tie a mecate to a bosal, and a multitude of wrong ways,” Krause warned. “I tie them the way Luis Ortega tied them. If I’m going to emulate somebody, it might as well be the master.

“I hold the mecate at arm’s length, and make sure there are no twists in it. The reins should come out toward the front end of the bosal, not at the heel end, and there should be only one wrap in front of the reins. That wrap controls how the bosal fits the horse’s face. If a horse is really sensitive, I’d loosen the tightness of that front wrap. Its leading edge will contact the bars of the horse’s face, so it’s important it’s in front of the reins.

“The get-down rope should come out at the heel.”

Spinning

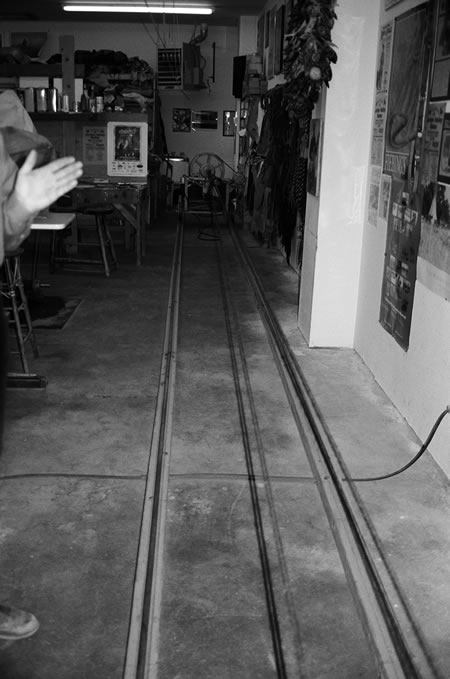

Fresh off the picker, the hair is gathered and rolled into a bun (photo 2). Next, Krause varies a little from tradition. Usually, the hair is twisted via a hook in the wall that someone cranks by hand or that’s powered by a can opener motor. Another person walks backwards, spinning the hair as they go.

Not Krause. He has a secret weapon that allows him to become competitive with mass-produced ropes—a machine called a spinner that was made specifically for Champlin. As far as Krause knows, it’s the only one in existence.

“It’s an integral part of our business,” Krause said. “I can sit here, spin thread, put it on spools, and then make ropes anytime I want. It’s very efficient. That machine is the reason we’re competitive.”

Hair from the bun is slowly fed to the spinner, which spins hair clockwise (photo 3). Krause spins three sizes of thread –small, medium (used in 90 percent of his ropes) and large for cowboy ropes. The size of thread is controlled by how much is fed from the bun. Also, the longer the hair, the looser he can make the thread. The shorter the hair, the tighter he must make it. How hard the thread is twisted also affects the feel of a rope.

Rope making

Simply stated, hairs make up threads, threads make up strands, and strands make up a rope.

After a spool of threads comes off the spinner, it goes to the rope maker. Each hook on this table-end corresponds to a strand. Here, Krause makes a six-strand rope (photo 4). He doesn’t make eight-strands, as he believes they are too soft and the signal doesn’t travel well from rider to horse.

“Different sizes of ropes have different numbers of threads in them,” he said.

“This is a 5/8-inch rope, which has four threads per strand. A 1/2-inch rope would have three threads per strand.”

Every strand stretches from the table end to a cart on tracks at the other end (photo 5). As the table twists threads into strands, the moveable cart shortens the length of the threads so there’s equal continuous tension on each strand. This prevents lumps and keeps the final products feeling the same. Six-strand ropes are then twisted around a mane hair core. (The core is made the same way as the rope but composed of less desirable hair.) Four-strand ropes have no core.

As the rope maker twists the threads, Krause walks back and forth to make sure the “dots” stay even—meaning, the white and black areas in the rope stay together and are evenly spaced (photo 6).

“This is where Blind Bob and Blind Sam had some problems,” he said. “If some white jumped in the middle of the black, they couldn’t see it. That creates a bunch of little dots in the rope, rather than bold ones. Any variation in thread size can cause hair to twist at a different rate, and some colors have more elasticity. You can have the same number of twists but more stretch. So depending on the hair, I might need to adjust the tension.”

After the proper tension is achieved, and the dots are even, the strands are twisted counter-clockwise into the final rope. Then a spreader is placed between the strands (photo 7). Weights keep constant tension on the core and strands. When the rope is removed from the machine, Krause uses a string to tie a seize knot at the table end of the rope to keep it from unraveling.

“Our ropes are consistent,” he said. “There are no lumps or bumps, and they’re tight but not hard. That makes a big difference. When you squeeze, there’s give. Tight ropes allow the signals to travel, whereas hard doesn’t.”

Tying the La Mota

Most people call it the tassel. “If you know knots well, you can determine who made the rope by the knot they tied,” Krause said. “There’s really no right or wrong way. I tie my knot around the core, whereas some folks tie the core, too.”

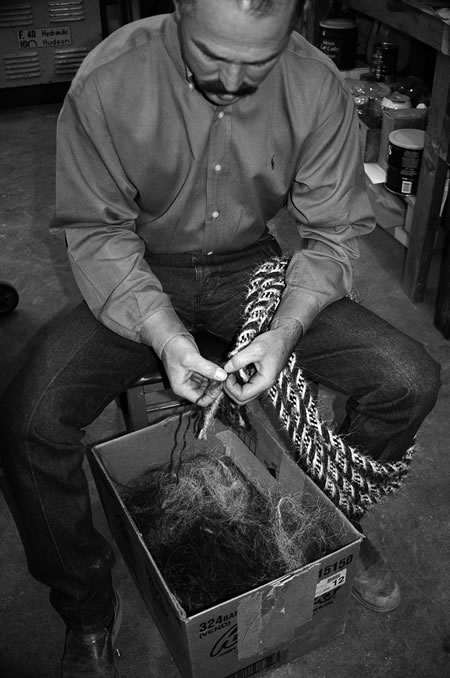

Here, Krause simply untwists the hair by hand, which will be reused (photo 8).

“Cowboys are the ultimate recyclers,” he said. “That’s what’s great about these ropes—traditionally, they were made for everyday use and utilized all renewable resources.”

The original length of the hair determines the basic length of the tassel. After the la mota is tied, Krause puts the leather popper on the end—he makes those, too. Once it gets the maker’s stamp of approval, the rope is done.

Longevity and Care

Chiefly because of the “secret weapon,” it takes Krause about three hours to make a rope. Cost depends on length, size and number of strands, but average price for a six-strand of this nature is around $150. That might sound expensive, but with proper care, a good horsehair mecate can last a lifetime.

“I have a 1940 Luis Ortega bosal with a Blind Sam rope on it that I still use,” Krause said.

The key is in the care. “When you’re done for the day, loosen the wraps on the bosal,” Krause advised. “Sweat and moisture can get in there and rot your mecate and your bosal. A purist would take the mecate off every day and hang it up, but most of us are realists.”

Also, don’t worry about the coarse feel. The mecate wears smooth with about two weeks of use.

“A lot of folks don’t understand that, and they try to clip or singe the bristles off—or they’ll wash it in Woolite,” Krause said. “Singeing the hair can actually make the rope more coarse; think about a long beard versus a short one. Washing the rope can make it soft and spongy, and the signal won’t travel as well.”

If your mecate does get muddy or otherwise dirty, Krause recommends rinsing it in water and hanging it in large coils to dry. Just be aware that every wash will change the feel a little.

Doug Krause of Krause Saddles and Mecates produces top-quality horsehair mecates, and reining, reined cow horse and working cowboy saddles. This is his 10th year co-sponsoring the National Reined Cow Horse Association Snaffle Bit Futurity with Ricotti Saddles of Clements, Calif., and he also sponsors the Hackamore Classic. Many industry notables use Krause mecates, including Robbie Boyce, Ted Robinson, Darren Miller and Carol Rose. He also supplies ropes to the working cowboys in the Great Basin ranches of Nevada.

Formerly based in Eaton, Colo., Krause now lives in Clements, Calif., and is employed by Ricotti Saddle Company. Additionally, he produces bosals through San Benito Braiding, a company he co-owns with Ricotti. For more information, contact him at 1-209-759-3550, or visit online at www.ricottisaddle.com.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.32