Horse Gear & Makers

The Elements of the Saddle Part 2: The Seat

Written by Chuck Stormes

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.13

Many of the nineteenth and early twentieth century saddleries were large firms doing much of their business by mail order. Depending on their market share, they employed from twenty to two hundred workers, including harness makers, strapworkers, saddlemakers and flower stampers.

The reputation earned by these shops was based in large part on the trees they used and the seats produced by their journeyman saddlemakers. Comfort for horse and rider equaled prosperity, even fame. Large numbers of these saddlers were trained in the older, eastern states or emigrated to the West from Britain or Europe, with skills acquired through a rigorous apprenticeship system. As in any manufacturing business, maintaining a high level of productivity was the key to financial success.

Saddlemakers typically worked on four to six saddles at a time for efficiency. These were often standard catalog models, possibly customized as to seat length, fender length or decoration. The result was a consistent, well-made, durable saddle with a standardized seat shape that was typical of that firm and required of every saddler in the shop. In the early 1960s, I learned the method and style of seat construction that resulted from those years of more or less standardized practice.

[symple_divider style=”solid” margin_top=”20px” margin_bottom=”20px”]

By the late 1960s, I had repaired and studied practically every brand of saddle I had ever heard of, from the legendary, such as Visalia, Hamley and Porter, to the virtually unknown. The best examples, made anywhere from Texas to western Canada, shared a common seat shape, allowing for minor variations.

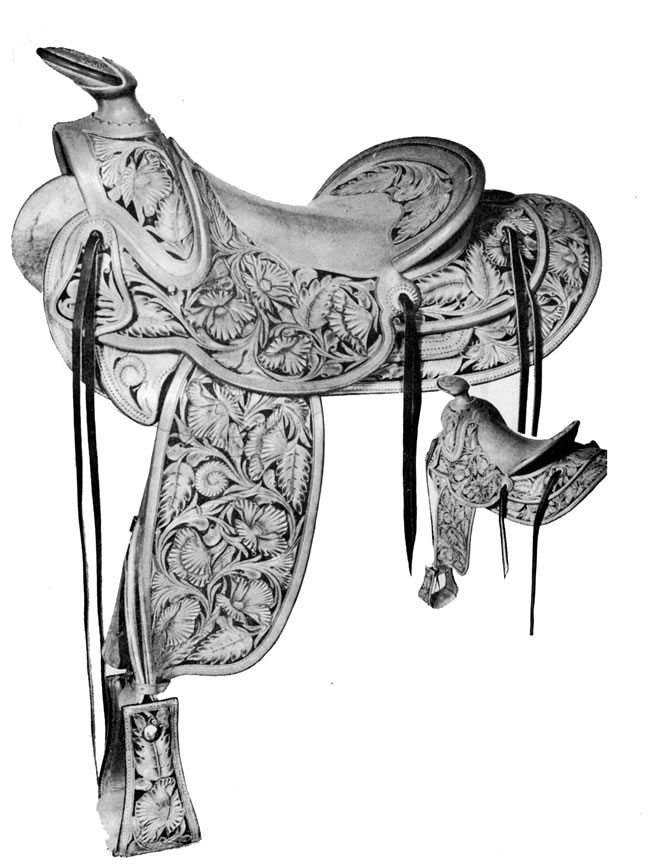

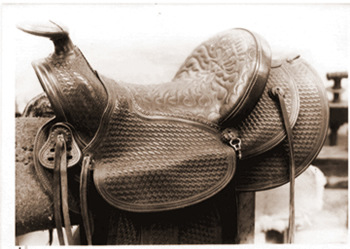

In a Western Horseman article from the 1950s renowned saddlemaker Ray Holes of Grangeville, Idaho, described the ideal seat shape in these terms: “The low spot here referred to should be in the centre of the place you would actually occupy while riding, or about one-third the distance from cantle to fork. This part of the seat should also be the narrowest looking down on it from the top. It should gradually widen out to blend with the fork in front and also gradually widen out to blend with the cantle in the rear. Looking at the saddle from the side, it should have a distinct curve in the seat, gradually raising both in front and behind this spot.”

To elaborate, this is the lowest area (where the rider normally sits when relaxed and settled into the seat) somewhat ahead of the base of the cantle and a few inches behind the center of the stirrup leathers. From this “sweet spot,” there is a widening and flattening to the rear, approaching the cantle and narrowing while rounding and rising toward the fork. These compound curves must flow smoothly, distributing the weight and pressure of the rider.

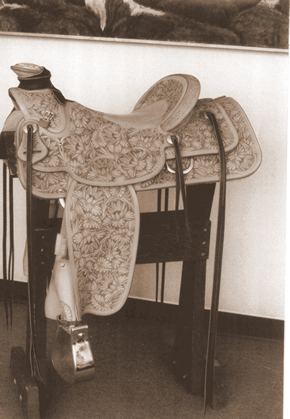

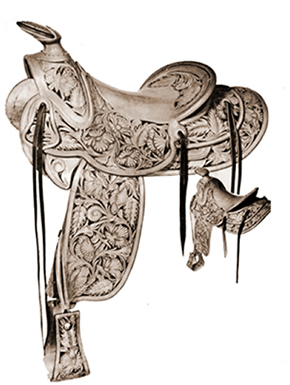

The accompanying illustrations hopefully show this shape more clearly than words. Accomplished saddlemakers, through experience, arrive at a mental image of their ideal seat, modifying it as necessary to suit the client’s needs. This seat, with minor adjustments, will suit the majority of riders—just as the standard bar structure fits the majority of horses’ backs. Except in extreme cases, custom-made does not mean “molded to the rider’s anatomy.”

The goal is even, equal contact between rider and saddle from the crotch to the calf, where the horse’s rib cage falls away from the rider’s leg, with no lumps, bumps or hollows to cause either an excess or absence of contact. While this sounds like a simple objective, it requires an experienced saddlemaker to achieve it while shaping the seat to allow the right combination of freedom versus security and maintaining the proper position of balance in relation to the stirrup leathers. I encourage serious students of horsemanship to be observant and develop an “eye” for the shape that constitutes a useful, balanced and comfortable seat. Variations of the basic seat shape can be made to accommodate physical deformity or injury or specialized horse sports, such as cutting or calf roping or to adjust the width for a woman’s saddle. The inside of the thigh is usually fuller and rounder than a man’s, requiring a seat that is narrower in the waist to maintain that even contact, beginning with the tree being made slightly narrower in that area. In the post-war years, saddleries employing a crew of journeymen began to be replaced by production-line factories.

Through erosion of saddlemaking skills and hiring cheaper, less skilled labor, the techniques required to produce correctly shaped seats were often lost, ignored or camouflaged with thick foam padding.

Those who took pride in their trade opened one- or two-man shops, spawning the present custom saddle industry. The best assurance of acquiring a saddle with a useful, comfortable seat is to educate oneself by riding a variety of saddles, analyzing their good and bad features and thereby developing an understanding based on experience. With that knowledge, seek out a skilled saddlemaker with a thorough grounding in the mechanics of the trade, who takes pride in the trade and is recommended by satisfied customers.

This article originally appeared in Eclectic Horseman Issue No.13